How Failing to Develop a Disruption Model Can Kill Good Companies

BlackBerry’s life as a vibrant, innovative company was over after two years of competing with two new market entrants, Google and Apple, because it failed to adapt to disruptive ‘process change.’

Photo Illustration by Scott Olson/Getty Images

After the launch of Apple’s iPhone, in the third quarter of 2008 to early 2009, BlackBerry, creator of the original smartphone device, saw its market share grow from 10 percent to 20 percent. Throughout the initial phase of the iPhone, BlackBerry thrived. But then, in a rapidly expanding market, growth stalled. By early 2010 BlackBerry began to falter, a decline that would see its two CEOs and founders step down and its once ubiquitous technology quickly become irrelevant.

In effect, BlackBerry’s life as a vibrant, innovative company was over after two years of competing with two new market entrants: Google and Apple.

What killed BlackBerry was the non-adoption of new processes (more on this below). In regard to smartphones, BlackBerry had its new models, and they were beautiful, but it was too late into their “process change” to make a difference.

The issue of non-adoption is generally not well covered in risk literature. Yet, what companies don’t find out about, what they overlook or stall on—especially when saying things like “We can’t execute and innovate” in the same breath—can be catastrophic. The new rules of business are surely that execution and innovation are one and the same. At least that’s the case when it comes to “process model innovation,” an area most executives shun.

Digital transformation is a further illustration of non-adoption’s dangers. In reality, few people know what this transformation involves or can identify the end goal, other than in casual terms, such as “being more nimble.” That lack of clarity is a non-adoption problem in the making; it hinders change because the casual language of transformation gives executives no real clue as to the end game. Where are today’s myriad digital transformation projects headed? One would be hard pressed to answer that.

There’s another big non-adoption risk. In January 2017, along with the Global Association of Risk Professionals (GARP), I surveyed 220 risk professionals about their intentions with regard to artificial intelligence (AI).

About 70 percent of risk managers believe AI represents a foundational change for their enterprise, yet only 15 percent of them are using it. More than 40 percent of risk managers believe AI’s significance is 1-3 years away, yet more than half of risk managers acknowledge having no plans to implement AI. Despite being in the business of risk, the majority has no risk mitigation plan for adoption or non-adoption.

BlackBerry’s Non-Adoption

The biggest risks to any company right now are process risks—the non-adoption of process model innovation. The global economy is changing and so, too, is how we organize for wealth creation. BlackBerry’s demise helps illustrate this.

In 2012, when BlackBerry COO Thorsten Heins took over the top job, he set about proselytizing the virtues of BlackBerry handsets, the company’s design capability, and the phone’s operating system. The solution he sought to people not buying in sufficient numbers was simply to build a better product. But the real problem lay in Heins’ other mission. He was trying hard, through a global tour, to persuade developers to build more apps for the BlackBerry.

Suddenly, hundreds of thousands of individuals and companies were creating apps for one company, a new market entrant at that: the hipsters from Cupertino. Not that Apple planned it. Contrary to claims made by some experts, Apple initially refused to host third party apps on the iPhone. The CEO, Steve Jobs, reluctantly relented nearly a year after the iPhone’s launch.

Actually, there was already a precedent for a highly scaled apps community on mobile. Palm Pilot, the hand held personal digital assistant (PDA), which also became a communicator, hosted 50,000 apps as early as 2005.

What Apple achieved, accidentally, was to scale an ecosystem beyond imagination. Jobs’ initial delay was a stark case of non-adoption—but one that he quickly put right.

What the business world also woke up to was that here was a new organizational form. A centralized transaction engine with an ecosystem of hundreds of thousands of peripheral partners operating under standard terms and conditions. Google meanwhile set out to emulate Apple, slowly at first, but gradually picking up momentum as device makers saw the advantages of a free OS (Android) and a collective pool of apps.

BlackBerry failed to understand how these ecosystems functioned and thus paid the heaviest price possible. Its distressed CEO took to the stage four years after the App Store launched, trying to drum up support from developers who were already making money from his competitors.

The Challenges of Convergence and New Enterprise Structures

The problem this example raises for CEOs stems from industry convergence. In mobile, the convergence with computing forced open the floodgates of change. Convergence, however, is becoming commonplace.

What do leaders in global logistics most fear? Companies in ecommerce. Who is best placed to eat the bankers’ lunch in transaction banking? Global platforms like Alibaba that integrate finance and trade.

In 2015 I described in detail how platforms shift and evolve, drive industry convergence and simultaneously cause the fragmentation of service delivery into ecosystems of smaller enterprises. Convergence is part of a wider industrial and geoeconomic shift.

This has been in evidence for some years, but very few enterprises are responding to it fast enough. They are running the risk of non-adoption across many new processes, with the banking industry being the most exposed.

The story of the convergence effect is complex, but here is a simple summary: Convergence is a critical disruptor.

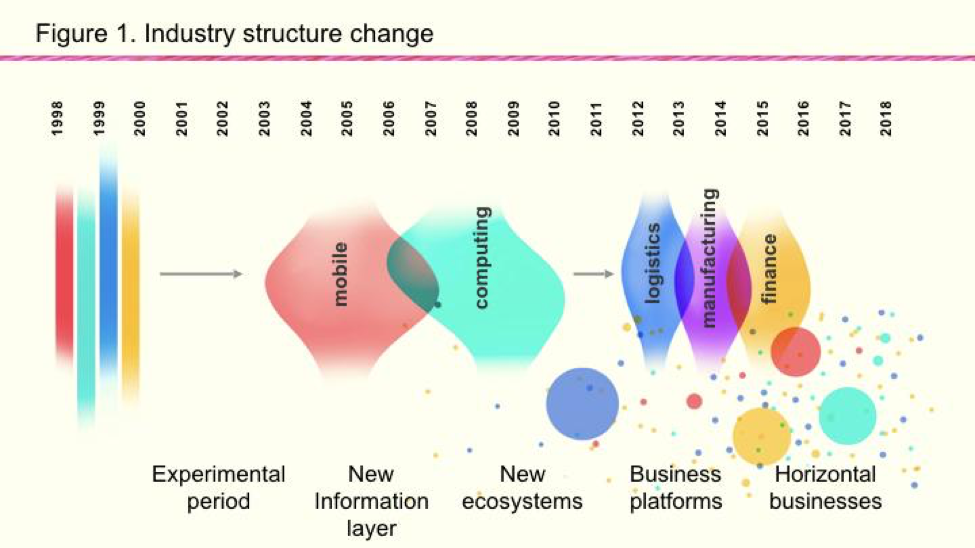

Figure 1 above shows the period from 1998 to today, characterized by, first, the convergence of mobile and computing and then by the convergence of other sectors.

As industries converge, this is the path disruption takes:

- Broad-based experimentation. Industries go through an experimental period where industry incumbents are challenged without success (look at today’s fintechs); experiments with mobile and computing operating systems and applications date back to the late 1990s—almost a decade before Apple succeeded with the App Store.

- New information markets. Newly emerging ecosystems of entrepreneurs are supported by new sources of information and by intense information exchange that promotes product/service-market fit (i.e., the signals between buyers and sellers).

- Emerging ecosystems. Dispersed business ecosystems grow from new entrepreneurial experiences gained during the experimental period.

- Business platforms. Platforms step in and organize existing economic activity, devolve innovation risk onto it, and then scale it up.

- The move to horizontal business. This leads to much more horizontal business activity across old sector boundaries, leaving all incumbents more exposed to competition.

Another consequence of this change is that platforms break out of 20th century economics. They delegate the risks of development and scale to third parties (the ecosystem). Therefore, as they grow they no longer suffer the burden of disproportionate cost that adds up—in conventional business—to diminishing marginal returns. This is a new source of power, coupled with an ability to apply platform thinking across sectoral lines and compete anywhere. As they are transaction engines, they also have an unprecedented liquidity advantage.

One of the biggest commercial risks right now is not understanding this basic pattern of change.

Layered on top of the platform and ecosystem model is huge scale, tremendous scope and a new speed of business.

A word on scale, scope and speed. The platform SAP Ariba added $300 billion in transactions to its procurement platform in the past year after it converged the supply chain with finance. Alipay, the financial subsidiary of Alibaba, is targeting 2 billion customers by 2026 (yes, that is billion). Amazon’s new business platform already had hundreds of millions of products on-boarded a year after launch.

Because they are so highly scaled, platform and ecosystem champions are driving the adoption of new processes such as AI, blockchain, and new data paradigms, as well as processes for continuous innovation and delivery (all elements of digital transformation). Each of these creates non-adoption risk that most companies struggle to explain to themselves.

You probably map your geopolitical risk, but do you ever compute the geoeconomic challenges ahead? All the changes above stem from three connected roots: changes in the global economic order, particularly the arrival (and sources) of hyper-scale; the convergence of industries; and changes in how enterprises organize for wealth creation. Not knowing the details expose CEOs to risks that many have yet to imagine.