Chinese Multinationals, Global Acquirers?

A man walks by a poster advertising the renminbi (RMB) currency (Chinese yuan) in Hong Kong. China has recently emerged as one of the top global investors and acquirers.

Photo: Laurent Fievet/AFP/Getty Images

China has significantly increased its outward foreign direct investment (OFDI) in the last 15 years, emerging as one of the top global investors. As late as 2000, China didn’t feature among the world’s top 15 investor countries; in 2015 it ranked third, with close to $128 billion in OFDI, just behind the U.S. and Japan.

In the process, China has also transformed itself into one of the most significant global acquirers, as its multinationals have increasingly taken the merger and acquisition (M&A) road to expand abroad.

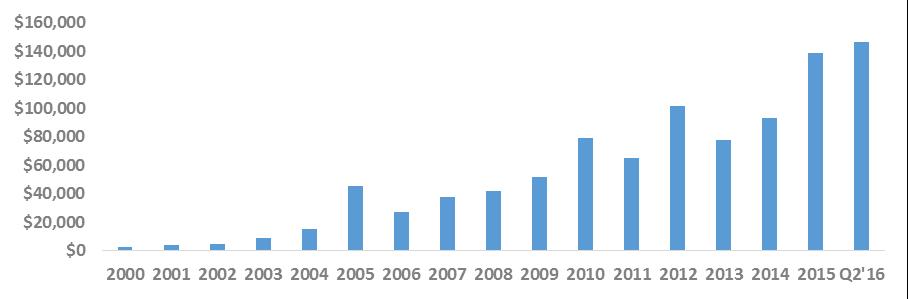

The value of announced overseas M&A deals by Chinese firms increased at an impressive speed after the global financial crisis. While China had no significant M&A activity in 2000, its value surged from less than $40 billion in 2007 to $140 billion in 2015. By June 2016, it had already exceeded the value achieved for the whole of 2015.*

Exhibit: Value of announced Chinese outbound M&A deals, 2000-Q2 16 (USD millions)

* Q2 16 data includes deals announced through to 16 June 2016.

Source: Authors’ analysis based on data from S&P Global Market Intelligence (2016), S&P Capital IQ Platform data, https://www.capitaliq.com (accessed August 2016).

Today, based on the value of announced deals, China is the fifth-largest global acquirer after the Netherlands, the UK, Canada and the U.S. Of the top 100 global transactions announced between July 1, 2015 and June 30, 2016, for example, 17 originated in China, which is the largest number of deals by a single country (according to data from S&P Global Market Intelligence, 2016). Some were of considerable size, such as the $43 billion announced acquisition of Syngenta by China National Chemical Corporation in February 2016. The U.S. was at the origin of 15 of the top 100 announced deals, followed by Canada (12), Germany (7) and the UK and France (6 each). Six Chinese acquisitions announced since 2008 have exceeded $10 billion. In 2016 alone, Chinese companies conducted 33 acquisitions valued at more than $1 billion each.

This buying spree may be expected to slow down in the months ahead for two reasons. First, changes in China’s policy and attitude toward OFDI—and M&As in particular; and second, reactions in target countries including increased scrutiny and protectionist attitudes, as well as sellers’ increased apprehensions

In China, a Shift in Policy

Government policy has played a key role in China’s transformation as a top player in global investments. The 2000 “Go Global” strategy marked the beginning of a proactive OFDI support policy, with a number of administrative, financial and commercial support measures administered by a network of government bodies and institutions comprised of the Ministry of Commerce, the National Development and Reform Commission, the Export-Import Bank of China, the China Development Bank and China Export and Credit Insurance Corporation.

Driven by the government’s desire to support its enterprises’ competitiveness through easier access to technology, markets and natural resources, overseas M&A deals by Chinese firms surged.

However, this has changed since late 2016. Concerned by downward pressure on the yuan and risk of destabilization resulting from significant capital outflows registered in 2015 and 2016, Chinese authorities have shifted their OFDI support policy toward more scrutiny and tighter regulations on capital outflows, including closer monitoring of Chinese firms’ M&As overseas—mainly of the large-scale acquisitions.

There was also fear that some recent acquisitions, especially by private companies, were motivated mainly by the desire to transfer money abroad—in particular when the acquired firm was outside the buyer’s core business. At the end of November 2016, the Chinese authorities announced that stricter approval requirements will be considered for deals worth more than $10 billion, or more than $1 billion if the acquisitions were outside the investor’s core business area. Moreover, real estate purchases abroad by state-owned enterprises (SOEs) for more than $1 billion would no longer be allowed. While new rules have yet to be formally released, Chinese authorities have indicated via the State Administration of Foreign Exchange that they would crack down on “fake” transactions.

In addition, leveraged buyouts may be more difficult to undertake, as Chinese authorities appear to be shifting toward tightening public financing policies. Such policies had enabled a number of firms, especially SOEs, to get access to cheap finance, in spite of high debt ratios. Non-financial SOEs, for example, have increased their debt-to-assets ratio since 2008 from 53 percent to 64 percent—which compares with a 70 percent debt-to-asset ratio reached in the U.S. before the 2008–2009 financial crisis.

Among the steps taken to deal with the situation, the People’s Bank of China is introducing a number of changes in its Macro Prudential Assessment (MPA) risk tool to control rising leverage in the nation’s financial system. The government is also reducing its explicit support of SOEs to encourage them to have healthier financing, even to the point that some SOEs have declared bankruptcy.

Given that overseas acquisitions have been largely credit-fueled, this will have the effect of dampening the appetite of Chinese companies—especially government-backed firms—for large-scale acquisitions, and will render overseas M&As more difficult to complete.

Overseas: Heightened Sensitivity and Protectionist Tendencies

The impressive surge in Chinese M&As, especially in developed countries, has also led to some vivid reactions in these countries. There are concerns for instance that, because of government support, Chinese firms benefit from a competitive edge over other enterprises, potentially crowding out other healthy private-sector companies.

Fears have also risen about national interests sliding under foreign control, with economic, political and national security implications. Particularly important in that respect is that a number of high-profile Chinese cross-border transactions have taken place in strategic technology sectors (such as robots, semiconductors), exacerbating political sensitivities in recipient countries. As a result, politicians in some Western countries have increasingly expressed their opposition to Chinese take-overs, leading governments to often block purchases on grounds of national interest.

For example, in 2016, the Australian government rejected several high-profile transactions, such as the sale of a majority stake in Ausgrid, an electricity provider, to State Grid Corporation of China. Midea’s successful purchase of the German robot manufacturer Kuka, seen by many as a symbol of Chinese appetite for Western technology, sparked strong objections from politicians and EU representatives. In an unexpected move, the German government withdrew its approval for the sale of a German chipmaker, Aixtron.

Earlier this year, three EU member countries—France, Italy and Germany—went further in their quest for stronger control and scrutiny of Chinese take-overs in sensitive industries. In a letter to the EU Trade Commissioner, they called upon the EU for a debate on the issue, with a view to create a legal basis to block state-backed deals in sensitive industries.

In the U.S., too, following objections from the Committee on Foreign Investment (CFIUS), a number of deals have been abandoned. In 2016, for example, the sale of Lumileds, the U.S.-based lighting unit of the Dutch conglomerate, Phillips, was stopped; similarly, the sale of chipmaker, Micron, a part of Western Digital, to the Chinese Tsinghua group was prevented; and Fairchild, a semiconductor maker, prompted by fear that the CFIUS would object to the deal, decided to not pursue negotiations with a potential Chinese acquirer, a group of state-backed enterprises.

Under the new U.S. administration, sellers’ apprehensions about dealing with Chinese buyers will likely increase.

Doubts are also emerging with respect to the post-deal situation of acquired firms, given the high levels of corporate debt in China and the lower level of government support mentioned above, creating some anxieties in target countries about the financial risks faced by the acquired firms in the post-acquisition period.

Despite the surge in 2015 and 2016, all of the aforementioned factors point to a likely decline of Chinese-led M&A transactions in 2017. That said, China still needs technology and know-how in value-added sectors. Its firms will continue to look for hard currency sources of incomes, and, over the longer term, for new markets. These are powerful drivers for a continuation of the Chinese M&A trend, at a lower but more sustainable level.

A more detailed perspective can be found here.