It’s Time to Rethink Islamic Banking Regulation

This photo illustration shows Malaysian ringgit banknotes in Kuala Lumpur on June 29, 2015.

Photo: Manan Vatsyayana/AFP/Getty Images

Modern Islamic banking, despite a relatively short three-decade history, feels a lot like conventional banking today. Although it uses Arabic terms and largely complies with elements of Shariah Law, Islamic banking began by replicating and mimicking conventional banking processes.

A replication strategy may have made sense in the nascent stages of Islamic banking, but today these banks, including ones in Malaysia and Brunei, have balance sheets that feel fairly similar to those of debt-based conventional banks. Their heavy reliance on “debt”-type contracts is exemplified by systems such as on the asset side. It is not uncommon for Islamic banks to have 80 to 90 percent of their total assets under such fixed-rate contracts.

To make matters worse, Islamic bank assets are dominated by long-term financing such as home mortgages and vehicle hire purchase, among others. Since the liability side has deposits that are short-term in nature, the duration gaps for Islamic banks are large—in many cases much larger than that of conventional banks.

Islamic vs. Conventional Banks

These large duration gaps mean that Islamic bank balance sheets are much more vulnerable to interest rate hikes than those of conventional banks—an ironic result given that Islamic banks are supposed to be operating in an interest-free environment. While global interest rates have reached historic lows in the past few years, they have recently begun to rise. Should inflationary pressure cause rates to rise rapidly, Islamic banks, especially those with large duration gaps, could be in serious trouble. Since the duration gap of assets is much larger than that of liabilities, asset value falls significantly more than that of liabilities. The result will be a huge squeeze on the net worth of the bank. Should an Islamic bank’s equity or net worth not be sufficient to take the squeeze, it will be rendered insolvent.

The same fate that befell American savings and loans in the 1980s and 1990s could happen to Islamic banks should rates rise fast. Conventional banks have smaller duration gaps in part because of their extensive use of floating rate loans and their flexibility to use derivatives such as interest rate swaps. So, where interest rate exposure is concerned, conventional banks have lower exposure than Islamic banks.

Apart from product profile, regulation has also helped to perpetuate, if not enhance, the problem. Conventional banks are required by regulators to follow Basel (BIS) requirements for capital adequacy. The IFSB (Islamic Financial Services Board) plays the same role for Islamic banks. Unfortunately, IFSB standards appear to have been formulated from the same BIS template. Thus, loan contracts have lower capital adequacy requirements than funding under risk-sharing contracts like Mudharabah or Musyarakah. While such requirements make sense for conventional banks that are really in the business of making loans, Islamic banking’s real value addition lies in the risk-sharing contracts of Islamic finance. Yet, IFSB requires capital adequacy ratios (CARs) of 300 percent for Mudharabah- and Musyarakah-type financing. This is at least three times higher than those of loan contracts like Murabahah or Ijarah. Given the punitive CARs, for Islamic banks competing within dual banking systems, it makes little economic sense to push risk-sharing contracts, even though they have the potential of being much more profitable.

Thus, one sees very little funding by Islamic banks under risk-sharing contracts in Malaysia and in other markets. Yet, the risk-sharing contracts being quasi-equity avoid the leverage, risk concentration and macroeconomic vulnerability of debt contracts. In many ways, regulation acts to hinder Islamic banks instead of enabling them to take advantage of their ability to provide risk-sharing contracts and truly differentiate themselves. Unless such requirements are reviewed, Islamic banking is bound to continue on its current path toward convergence.

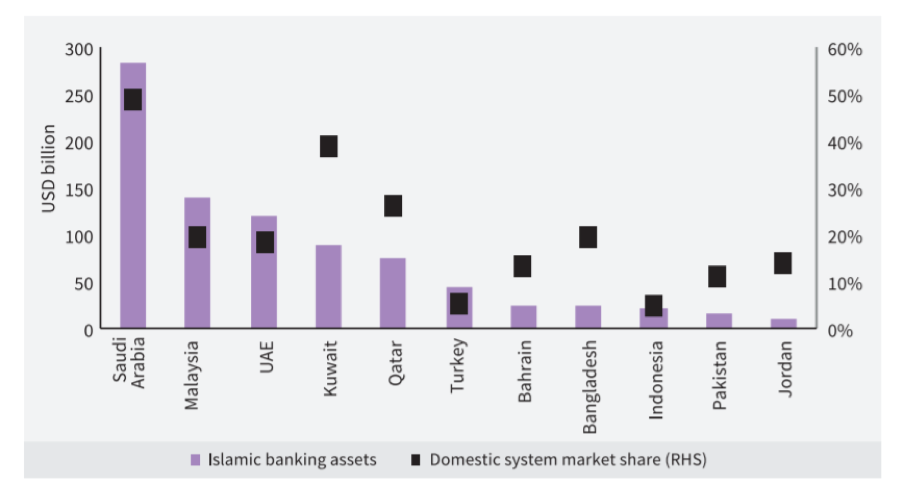

Exhibit: Islamic Banking Assets and Market Share (June 2015)

How can Islamic Banking Bounce Back?

When Islamic banks produce the same outcomes, and cause the same externalities as conventional banks, they bring little value-add to society. Furthermore, competing with conventional banks on loan-based financing is a losing proposition. Conventional banks have far more advantages in loan origination than Islamic banks, and their size and scale cannot be matched. As such, for Islamic banking to grow market share, it has to move away from offering the same services as conventional banks and use more risk-sharing contracts, as that is where the real value-add of Islamic finance/banking lies.

If Islamic banks are to thrive in the long run, there is an urgent need for them to rethink their business model. Moving away from loan origination to participatory risk-sharing finance can change the game, but Islamic banks need to be helped to make that change. For a start, the regulatory and supervisory models for Islamic banking need to change and become more accommodative. One cannot expect different results while doing the same things.