The AIIB and Shifting Economic Dynamics in Southeast Asia

Representatives of the founding nations of the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank (AIIB) walk around a sculpture after it was unveiled during the opening ceremony of the AIIB on January 16, 2016 in Beijing, China.

Photo: Mark Schiefelbein/Pool/Getty Images

The China-led Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank, which seeks to help plug Asia’s infrastructure-funding gap, has begun shifting the economic balance of power and influence in Southeast Asia, a region in which Japan and the United States have traditionally been the key external economic players.

The AIIB’s Growing Prominence

While the AIIB has a capital base of $100 billion currently, the Asian Development Bank (ADB) and the World Bank have a capital base of $160 billion and $223 billion, respectively. In 2015, the World Bank and ADB combined gave out loans worth $55 billion, a far cry from the $8 trillion the ADB forecast would be needed between 2010 and 2020 to meet Asia’s infrastructure development requirements.

Secondly, the World Bank and the ADB usually take two to three years to assess a single project, which is too slow to accommodate fast-growing needs in emerging markets. The AIIB, on the other hand, places fewer conditions on countries when offering loans; the privatization of state-owned companies and deregulation of business are not mandatory, for example. The bank also claims to ensure the transparency of projects. By promising to be “lean, clean and green,” it seeks a better solution to the trade-off between economic growth and social and environmental considerations.

To close the infrastructure-funding gap efficiently, China attempts to set new investment standards through the AIIB by disbursing funds more swiftly, and can do so owing to its effective veto power (26 percent voting right) within the bank.

Competing Interests in Southeast Asia

Outward flow of investments from China have been increasing in recent years, and in 2015, China’s outbound foreign direct investment (FDI) reached $146 billion, surpassing inbound FDI flow into China.

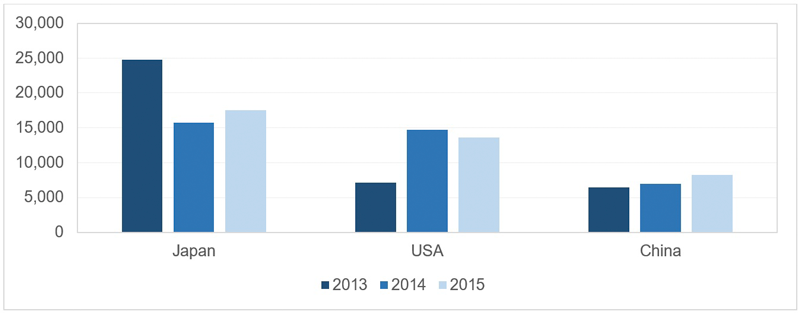

Today, China is the third-largest investor in Southeast Asia, after Japan and the U.S. In 2015, China was the No. 1 trade partner to Cambodia, Malaysia, Singapore, Thailand and Vietnam, whereas Japan was the No. 1 trade partner to Brunei and the Philippines.

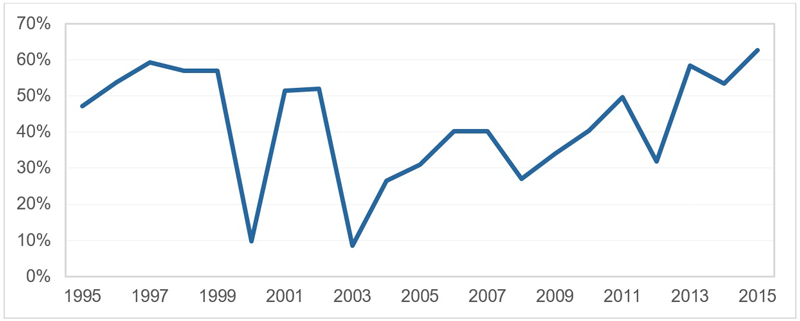

Historically, Japan increased its FDI in Southeast Asia after the appreciation of the yen, following the Plaza Accord in 1985. Ever since, Japan has become the major FDI investor in Southeast Asia. It is the largest FDI source country for ASEAN for the past five years, with an average inflow of $20 billion per year, except in 2012, due to the Thai floods. Furthermore, the increasing proportion of Japanese FDI in the ASEAN region to total Japanese FDI in Asia since 2003 indicates a trend whereby Japanese investors are shifting their capital from other parts of Asia to Southeast Asia.

China, Japan and the U.S. are all competing for economic interests in Southeast Asia, while ASEAN itself—with its 625-million population—is projected to become the fourth largest economy by 2030. There is uncertainty as to whether the U.S. will maintain its current level of engagement in the region during President-elect Donald Trump’s administration, given his skepticism toward the Obama administration’s “rebalancing” strategy in Asia and his pledge to pull out of the Trans-Pacific Partnership trade deal on his first day in office.

On the other hand, the Japanese government announced the Partnership for Quality Infrastructure in 2015. This partnership will provide $110 billion for high quality infrastructure investment in Asia in collaboration with the ADB.

The AIIB in Southeast Asia

The decision by the U.S. and Japan to not join the AIIB has led to ambiguity over whether it is the best investment practice of China or of Japan and the U.S. that will prove to be effective in removing the development bottlenecks in Southeast Asia. Irrespectively, China’s increasing influence alongside trade and investment activities means a relative decline of U.S. influence in this region. Given Japan’s strong desire for infrastructure export and business interests in Southeast Asia, it would have been in keeping with its economic interests to participate in the AIIB and influence the bank from within. The decision to not do so signals Japan’s difficulties in searching for the right strategic balance between the new and the old. Given the U.S.-Japan security alliance, Japan is deeply embedded in the existing order beyond the security arena, and is cautious about China’s initiatives.

China would buttress its ascendency in the region if its currency comes to be accepted as a global currency for reserve and trade transactions. If so, the yuan will substitute the role played by the U.S. dollar in the region, something that Japan did not achieve even after the Plaza Accord. Growing Chinese investment and finance in the yuan will gradually reduce transaction costs and exchange rate risks faced by Chinese companies and financial institutions. There is, however, a long way to go before interest rates and exchange rates are freely determined by market forces and China’s current account is opened. On its own, the AIIB can contribute towards the internationalization of the yuan by issuing yuan-denominated bonds.

A Common Goal

The AIIB is already cooperating with the ADB and the World Bank, which are co-financing five of its six projects. Such collaboration between the AIIB, the ADB and the World Bank will ensure the complementary role that each of these institutions play in development finance. Sustainable economic development will not be achieved without economic governance that is conducive to physical and human investment, efficient allocation of capital and labor and entrepreneurial activities.

There is very little that multilateral development banks can do for poor countries in the region without the countries having legal and bureaucratic structures that are open, efficient and transparent. Moreover, effective state capacity-building will be the major challenge for all countries.

By successfully linking major cities with railways and highways and by building power plants, seaports and airports, China has laid the infrastructure for its industrialization and economic miracle. The challenge for others—and China—is to imitate China’s success beyond its borders.