China Can’t Finance ‘Belt and Road’ Alone

Chinese President Xi Jinping delivers his speech during the welcoming banquet for the Belt and Road Forum at the Great Hall of the People in Beijing, China May 14, 2017.

Photo: Damir Sagolj—Pool/Getty Images

The One Belt One Road Initiative holds great promise for the global economy, but it needs a huge amount of financing. Initial presumptions that China would be able to provide all of the financing are now unrealistic. Other partners should consider providing finance for some aspects, especially Europe, which has much to gain from the project.

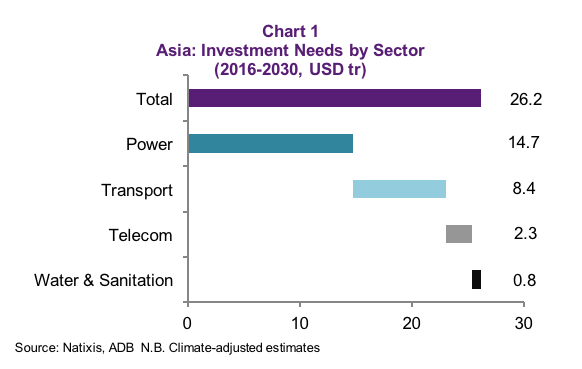

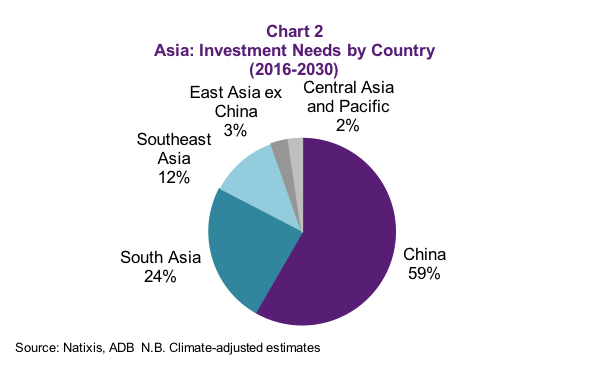

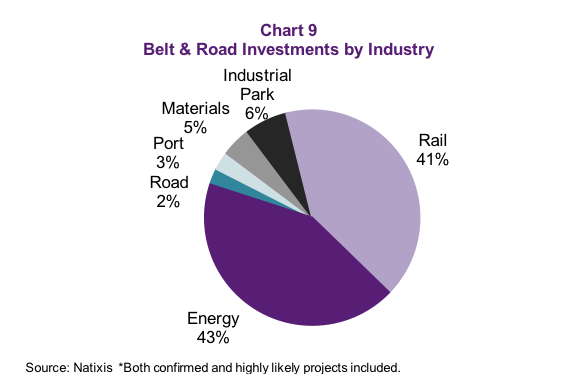

There is no doubt that Asia needs infrastructure. The Asian Development Bank (ADB) recently increased its already very high estimates of the amount of infrastructure financing needed in the region to $26 trillion in the next 15 years, or $1.7 trillion per year (Chart 1). The great thing about the China-driven Belt and Road Initiative is that it aims to address that pressing need for infrastructure, especially in transport and energy infrastructure. But this is easier said than done. The theory is that the financing will be there thanks to China’s massive financial resources.

Chinese authorities have come up with their own estimates of the projects that will be financed. The numbers start at $1 trillion and go all the way to $5 trillion in only 5 years. In the same vein, the official list of countries does nothing but increase over time to more than 65—but there is a limit to how much China can finance.

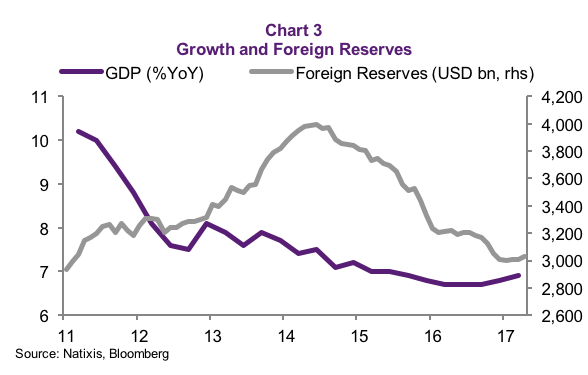

Such reasoning was probably well taken when China was flooded with capital inflows and reserves had nearly reached $4 trillion and needed to be diversified. Chinese banks were then improving their asset quality if anything, because the economy was booming and bank credit was growing at double digits.

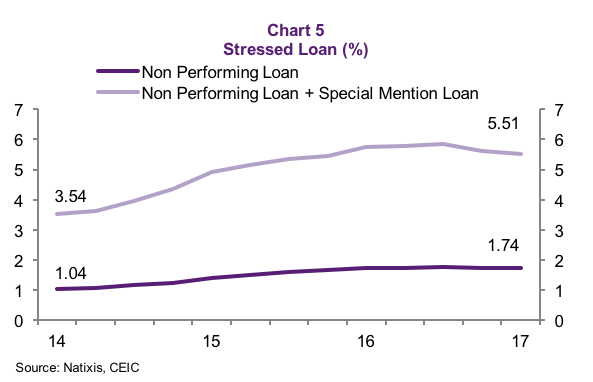

The situation today is very different. China’s economy has slowed down and banks’ balance sheets are saddled with doubtful loans, which continue to be refinanced and do not leave much room for the massive lending needed to finance the Belt and Road Initiative.

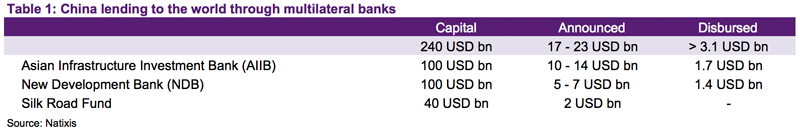

This is particularly important as Chinese banks have been the largest lenders so far (China Development Bank in particular with estimated figures hovering around $100 billion while Bank of China has already announced its commitment to lend $20 billion). Multilateral organizations geared toward this objective certainly do not have the financial muscle. Even the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank (AIIB), born for this purpose, has so far only invested $1.7 billion on Belt and Road projects.

As if this were not enough, China has lost nearly $1 trillion in foreign reserves due to massive capital outflows. Although $3 trillion of reserves could still look ample, the Chinese authorities seem to have set that level as a floor under which reserves should not fall so that confidence is restored (Chart 3). This obviously reduces the leeway for Belt and Road projects to be financed by China, at least in hard currency.

How to Finance the Belt and Road?

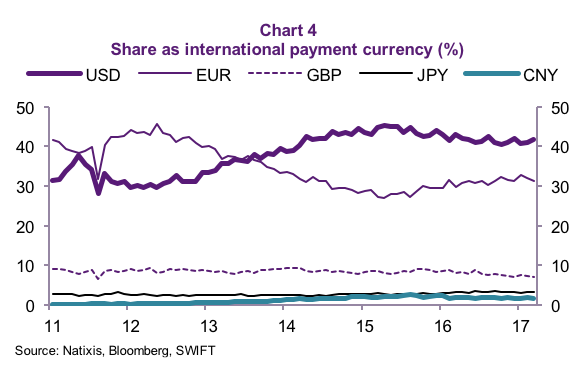

The first, and least likely, step is for China to continue such huge projects unilaterally. This is particularly difficult if hard-currency financing is needed for the reasons mentioned above. China could still opt for lending in yuan, at least partially, with the side benefit of pushing yuan internationalization. However, even this is becoming more difficult.

The use of the yuan as an international currency has been decreasing as a consequence of the stock market correction and currency devaluation in 2015, but still some of the Belt and Road projects could be financed in yuan in as far as the borrowing of a certain host country would be fully devoted to pay Chinese construction or energy companies (Chart 4). This quasi-barter system can solve the hard-currency constraint but poses its own risks to the overly stretched balance sheets of Chinese banks. In fact, their doubtful loans have done nothing but increase during the last few years, which is eating up the banks’ room to lend further (Chart 5).

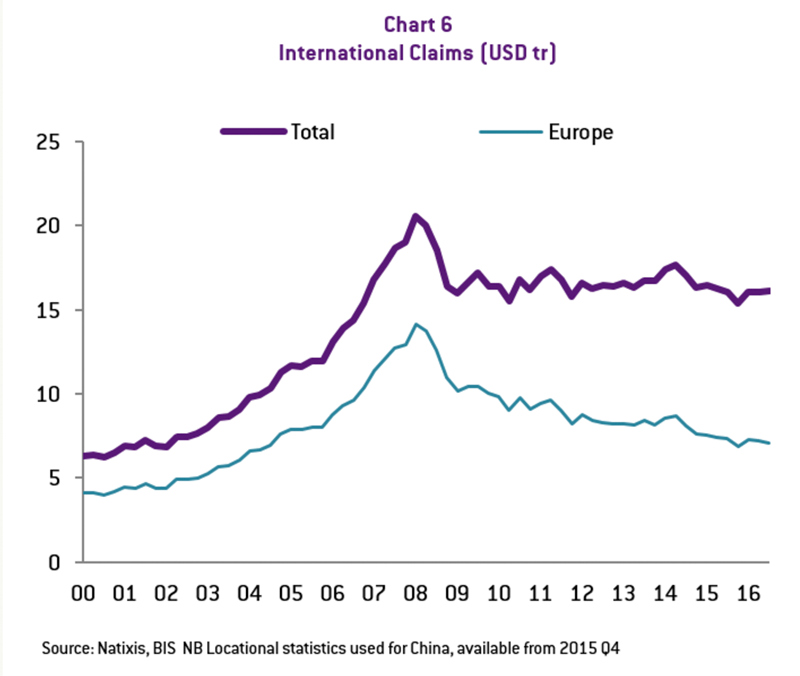

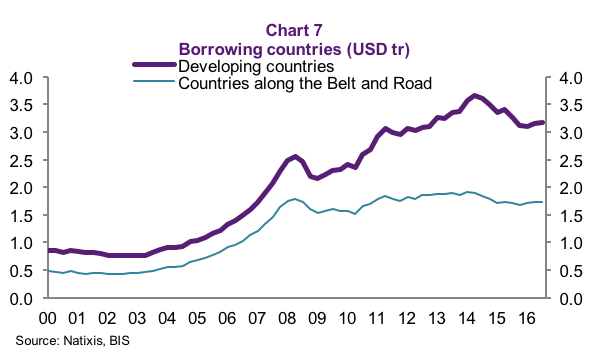

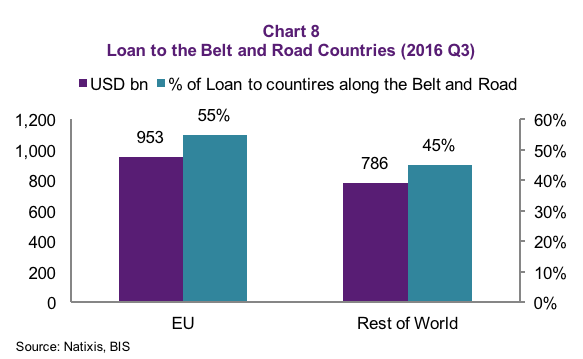

A second option is for China to intermediate overseas financial resources for the Belt and Road projects. The most obvious way to do this, given the limited development of bond markets in Belt and Road countries, as well as the still-limited size of China’s own offshore bond market, is to borrow from international banks. Cross-border bank lending has been a huge pool of financial resources, especially in the run up to the global financial crisis. Since then they have moderated, but the stock of cross-border lending still hovers above $15 trillion, out of which, nearly half is lent by European banks. Out of the $15 trillion, about 20 percent is already being directed to Belt and Road economies, again with European banks being the largest players (Chart 7).

Still, in order to finance the $5 trillion targeted in Xi’s grand plan for the next five years, we would need to see growth rates of around 50 percent in cross-border lending. While such a surge in cross-border lending is not unheard of (in fact, it happened in the years prior to the global financial crises), the real bottleneck would be the rapid increase in China’s external debt, which would go from the currently very comfortable level (12 percent of GDP) all the way to more than 50 percent if China were taking on the debt, or something in between if co-financed by Belt and Road countries.

A mix of options one and two lies on the use of multilateral development banks to finance the Belt and Road projects. In fact, China is a major shareholder of its newly created multilateral banks (AIIB and New Development Bank) but less so in existing ones (such as ADB, EBRD or the World Bank). This means that the financing burden can be shared (to a lesser or larger extent) with other creditors, while still keeping a tight grip on the construction of such infrastructure (at least in new China-led organizations). While apparently ideal, the problem with this option is that the available capital in these institutions is minimal compared to the financing needs previously discussed (Table 1).

It seems that China cannot rely on its banks alone—no matter how massive—to finance such a gigantic plan. The key source of co-finance would logically be Europe, at least as long as bank lending dominates, which will be the case for quite some time in the countries under the Belt and Road. In fact, European banks are already the largest providers of cross-border loans to these countries, so it is only a question of accelerating that trend. Furthermore, the geographical vicinity between Europe and some of the Belt and Road countries could make the projects more appealing (Chart 8 and Chart 9).

In addition, the European Union has its own grand plan for the financing of infrastructure—among other sectors—namely the Juncker Plan, which could serve as a basis to identify joint projects of interest to both the EU and China. The EU-China connectivity platform was launched by the European Commission in late 2015 to identify projects of common interest for the Belt and Road and EU connectivity initiatives, such as the Trans-European Transport network. All of this bodes well for Europe to become an active part of China’s Belt and Road Initiative, not only in providing the financing, but also in identifying projects of common interest.

It goes without saying that other lenders, beyond Europeans, are welcome to finance Belt and Road projects as the ensuing reduction in transportation costs and improved connectivity should be good for the world as a whole. However, Europe’s particular advantage in this project should make it a leader on the financing front bringing the old continent closer to China.

The Belt and Road is great for supporting high demand in Asian infrastructure, but there is a limit on how much China can finance. The slowdown of the economy and the limits on the use of foreign reserves are two of the impediments. Additionally, Chinese bank balance sheets, the largest source of financing so far, are increasingly saddled by doubtful loans, which limit their lending capacity. As for official multilateral development agencies, their funding sources remain limited for the extent of the project.

Against this background, European banks—the largest cross-border lenders in the world—are well placed to step-up their already large financing to Belt and Rod countries. Europe’s proximity with some of these countries can make certain projects more appealing for Europe as well. Thus, we should expect private and public European co-financing of Belt and Road projects to increase over the next few years and, with it, European interest for Xi Jinping’s grand plan. This should bring Europe closer to China.