The Geopolitical Impact of China’s Economic Diplomacy

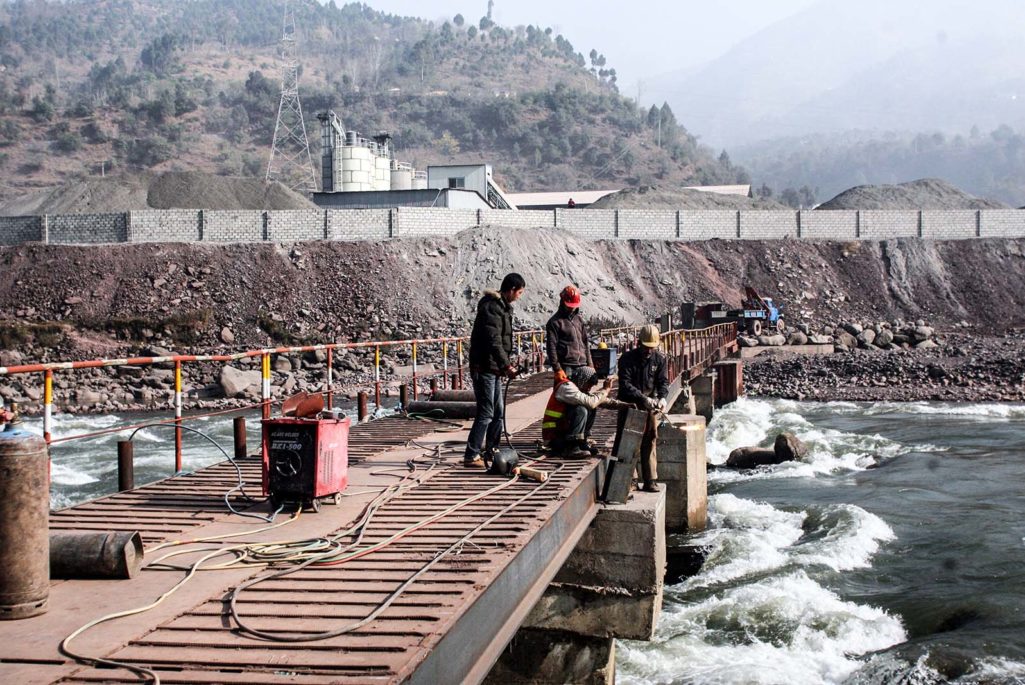

A Chinese engineer (L) supervises workers building a bridge over a river in Ghari Dopatta, some 22 kms from Muzaffarabad, the capital of Pakistani-administered Kashmir. Chinese companies are working on more than 100 major projects in energy, roads and technology in Pakistan.

Photo: Sajjad Qayyum/AFP/Getty Images

The prevailing conventional wisdom of a singularly powerful, hegemonic China is too simplistic; the interconnected geo-economics of today’s world, though often stark and abrupt, are woven from a set of complex and nuanced political realities surrounding the execution of China’s economic diplomacy.

That was the uptake from a recent public forum, hosted by the Brookings Institution, in which a panel of Asia experts made the case that despite the enormous influence China exhibits across the globe today, the story of Asia’s future would be written by many Asian countries.

Although much of the event’s conversation avoided China—focusing instead on other players such as Japan, South Korea, the United States and Australia—the economic superpower loomed over the talk much as it looms, politically and economically, over Asia.

The event, titled The Geopolitical Impact of China’s Economic Diplomacy, wove an intricate tapestry of competing political interests and subverted economic expectations to be played out by a cast of nations hoping for a reshuffling that might tip the balance of the region in their favor.

David Dollar, a senior fellow at Brookings’ Thornton China Center, began by laying out the stakes: according to a recent Asian Development Bank report, developing countries in Asia need to invest roughly $26 trillion into infrastructure by 2030, far more than previously anticipated.

“In recent years, the rich countries as a group have not been doing very much to meet these needs,” Dollar said.

China, on the other hand, is well-positioned to help developing countries meet those needs, Dollar said. “You’re seeing some labor-intensive value chains moving out of China,” he continued. “You see Chinese construction companies that do not have enough business at home. So I think from China’s point of view this capital going out makes enormous economic sense.”

‘China is not the only country that is proposing huge cross-border international projects.’

‘Not Just a China Story’

In light of the Belt and Road Initiative, China might appear to be the strongest candidate to help fund infrastructure demands in the region. However, China’s leadership in this area was disputed by Masahiro Kawai, the director-general of the Economic Research Institute for Northeast Asia.

“Internationally there are so many initiatives, even for the Northeast Asian countries,” Kawai said. “Mongolia has its own initiative called the Steppe Road initiative which connects Mongolia with neighboring countries and distant countries,” Kawai said. “Korea has the Eurasia[n] Initiative, which connects Korea with Eurasian countries. And Russia has its own initiative—Siberian transport system and Eurasian economic partnership initiative [Eurasian Economic Union]. And there are many other such projects driven by various national governments.”

“China is not the only country that is proposing huge cross-border international projects,” Kawai said.

Moreover, although Kawai acknowledged the expectation that China would reshape the international economic system to be consistent with its interests, he pointed out that other, smaller countries were the ones pushing for change. China, instead, appeared to be pulling back in the interest of maintaining the status quo.

One example of this, Kawai said, were the efforts of Australia, Japan and New Zealand to finalize large free trade agreements despite a withdrawal of support from China or India, the expected key players in the region.

“The U.S. is backtracking, which is very unfortunate,” Kawai said. “But does this make China an aggressive leader? […] China doesn’t seem to be taking leadership by opening its economy and then embracing many other countries to consolidate a [free trade agreement] under [the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership]. That’s not what’s happening.”

Evan Feigenbaum, vice chairman of the Paulson Institute, reiterated this point, and suggested that Asian history could serve as a helpful guide for assessing the current geopolitical reality.

“[When China announced the Belt and Road Initiative] people said ‘Oh my god, China’s got this new big strategic initiative, how are we going to react to this?’ as if connectivity in Asia had been invented in China, invented in 2013, and like Athena from Zeus’s head had sprung from the head of President Xi Jinping,” Feigenbaum said. “It’s easy to forget that for most of its history Asia was an astonishingly interconnected place.”

Feigenbaum insisted current changes in the region were far more than “just a China story” or “just an infrastructure story.” Instead, the region’s new connectivity was indicative of Asia at large—not just China—becoming more Central Asian than Eurasian. These were the first signs of a reversion back to historical norms, and away from the “anomaly” of the past century—which had been instituted by Western countries.

The U.S. on the Brink of Economic Irrelevance

During his presentation, Kawai raised the following question: “Does China want to challenge the existing system and somehow change [it] in a way that is consistent with China’s overall political, economic, and even security interests, or is China [executing trade policy] in a way consistent with the existing economic system?”

An underlying assumption of this question, and of the event’s discussions at large, was that the U.S. had retreated from Asia: this had the result of disempowering one set of economic elites, and subsequently empowering another.

Dollar explained that the U.S. and China had previously complemented each other economically in the region. The real question about Asia’s future, then, is whether China will fill the gap left by the U.S. and other Western powers whose influence is waning.