Global Fossil Fuel Emissions Have Stalled

Smoke billows from smokestacks and a coal fired generator at a steel factory in the industrial province of Hebei, China. After strong growth since the early 2000s, fossil fuel emissions in China have leveled off and may even be declining.

Photo: Kevin Frayer/Getty Images

For the third year in a row, global carbon dioxide emissions from fossil fuels and industry have barely grown, while the global economy has continued to grow strongly. This level of decoupling of carbon emissions from global economic growth is unprecedented.

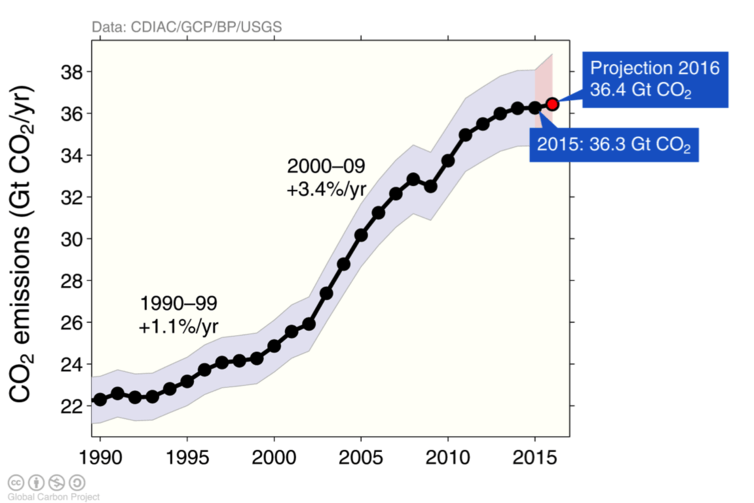

Global CO₂ emissions from the combustion of fossil fuels and industry (including cement production) were 36.3 billion tonnes in 2015—the same as in 2014—and are projected to rise only 0.2 percent in 2016, to reach 36.4 billion tonnes. This is a remarkable departure from emissions growth rates of 2.3 percent for the previous decade and more than 3 percent during the 2000s.

Given this good news, we have an extraordinary opportunity to extend the changes that have driven the slowdown and spark the great decline in emissions needed to stabilize the world’s climate.

This result is part of the annual carbon assessment released by the Global Carbon Project, a global consortium of scientists and think tanks under the umbrella of Future Earth and sponsored by institutions from around the world.

Fossil Fuel and Industry Emissions

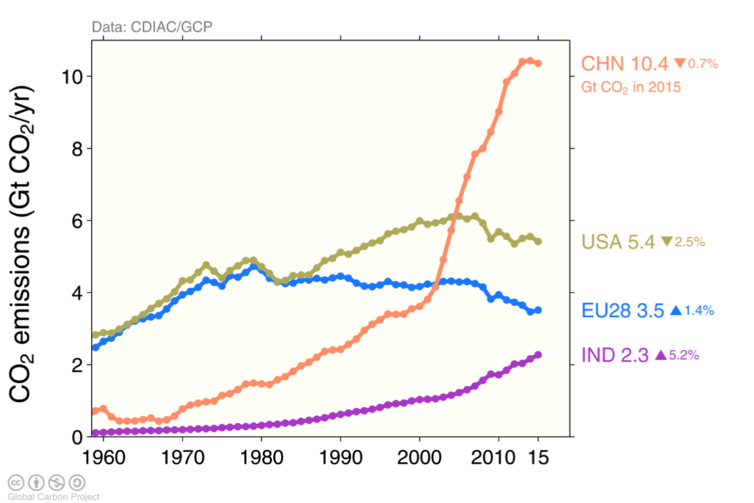

The slowdown in emissions growth has been primarily driven by China. After strong growth since the early 2000s, emissions in China have leveled off and may even be declining. This change is largely due to economic factors, such as the end of the construction boom and weaker global demand for steel. Efforts to reduce air pollution and the growth of solar and wind energy have played a role too, albeit a smaller one.

The United States has also played a role in the global emissions slowdown, largely driven by improvements in energy efficiency, the replacement of coal with natural gas and, to a lesser extent, renewable energy.

What makes the three-year trend most remarkable is the fact that the global economy grew at more than 3 percent per year during this time. Previously, falling emissions were driven by stagnant or shrinking economies, such as during the global financial crisis of 2008.

Together, developed countries showed a strong declining trend in emissions, cutting them by 1.7 percent in 2015. This decline was despite emissions growth of 1.4 percent in the European Union after more than a decade of declining emissions.

Emissions from emerging economies and developing countries grew by 0.9 percent, with the fourth-highest emitter, India, growing at 5.2 percent in 2015.

More importantly, the transfer of CO₂ emissions from developed countries to less developed countries (via trade of goods and services produced in places different to where they are consumed) has declined since 2007.

Deforestation and other changes in land use added another 4.8 billion tonnes of CO₂ in 2015, on top of the 36.3 billion tonnes of CO₂ emitted from fossil fuels and industry. This is a significant increase of 42 percent over the average emissions of the previous decade.

This jump in land use change emissions was largely the result of increased fires at the deforestation frontiers, particularly in Southeast Asia, driven by dry conditions brought by a strong El Niño in 2015-2016. In general, though, long-term trends for emissions from deforestation and other land use change appear to be lower for the most recent decade than they were in the 1990s and early 2000s.

The Carbon Quota

When combining emissions from fossil fuels, industry and land use change, the global economy released another 41 billion tonnes into the atmosphere in 2015 and will add roughly the same amount again this year.

We now need to turn this lack of growth to actual declines in emissions as soon as possible. Otherwise, it will be a challenge to keep cumulative emissions below the level that would avoid a 2 degrees Celsius warming, as required under the Paris Agreement.

As part of our carbon budget assessment, we estimate that cumulative emissions from 1870 (the reference year used by the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change to calculate carbon budgets) to the end of 2016 will be 2,075 billion tonnes of CO₂. The remaining quota to avoid the 2 degree threshold, assuming constant emissions, would be consumed, at best, in less than 25 years (with remaining quota estimates ranging from 450 to 1,050 billion tonnes of CO₂). Ultimately, we must reduce emissions to net zero to stabilize the climate.

This piece first appeared on The Conversation.