How Do You Capture the Economic Value of Free Digital Services Such as Search?

An interview with

A person is using their tablet to access multiple social media accounts. The most valued digital good to consumers is a search engine, followed by social media, which generates a revenue of $400 to $500 of value every year.

Many economists say that gross domestic product (GDP) isn’t measuring the full value of the digital economy. Because many digital goods, like search, are effectively free, the welfare gains from these goods are not reflected in productivity statistics.

Researchers at the MIT Sloan School of Management have come up with an innovative method of capturing the value of these digital services. By using massive online surveys, they discovered how much value consumers place on free services such as Facebook or Google search. They recently published their findings, and BRINK spoke with Avinash Collis, one of the lead investigators in the MIT Measuring the Economy Project.

BRINK: What’s the current issue with GDP as a metric?

Avinash Collis: That’s a great question. So, for most of the 20th century, when goods had prices, GDP was a pretty good measure of well-being, as a proxy. Let’s say you paid for an automobile, for haircuts, or food or any other product. If we consume more of these products, GDP would go up and people are better off.

So, at least they are correlated and move in the same direction. But, when it comes to the digital age, when the price of the good goes down to zero, it shows up as almost zero in GDP (part of it shows up indirectly through advertisements and prices of goods that are advertised, but advertising revenues and consumer welfare need not be correlated).

To give you an example: Let’s say you start using more and more Google Search or Facebook or WhatsApp. If you increase your consumption of these goods, GDP wouldn’t change much, because you’re not paying anything to use them more. But at the same time, you are better off because you are using it more.

This relationship gets even worse when digital goods replace physical goods for which we used to pay positive prices. The really good example of this is the encyclopedia industry. So, we used to spend hundreds of dollars buying volumes of the Encyclopedia Britannica. Now, we just go onto Wikipedia and get the content for free. As a result of this shift, the contribution of the encyclopedia industry to GDP goes down, but consumers are better off.

BRINK: So there’s clearly a problem. How did you set about trying to solve it?

Mr. Collis: We decided to go out and directly measure how much people benefit from these goods. So instead of seeing how much people pay for these goods, which doesn’t work in the digital age, we asked the question, “How much are you valuing these goods? How much benefits in terms of dollars are you getting from using these digital goods?”

And the way we do it is by running lots of online choice experiments. So we ask thousands of people, “Would you give up Facebook or Google or Wikipedia or any of these products, for a week or a month, in exchange for $5, $10, $50, etc. a month?” Aggregating responses from all of these subjects online lets us estimate the valuations and demand curves for these goods.

BRINK: But that’s just an estimate of what someone would pay to give it up. It’s not the same as saying, “How much does this add value to a business?” Right?

Mr. Collis: So, all of the results in the research so far are looking directly at the impact on the consumers well-being. We haven’t looked at the impact when a business adopts information technology and how that impacts their productivity.

BRINK: So, you’re purely looking at this in terms of the direct benefit to the consumer, as opposed to, indirectly through lower costs of goods and so forth?

Mr. Collis: Yes, exactly.

BRINK: Is this tool robust enough to be adopted as a standard for measurement of digital value?

Mr. Collis: We tried out several different approaches, and all of these approaches led us to similar results. So, the methods seem to be robust because we are not simply asking hypothetical survey questions—How much do we value Facebook,? etc.—but rather, we actually enforce their choices. We give them a chance to get real cash for giving these services up.

There is a lot of noise in the responses, and we are still working on improving the precision of our estimates. But in general, our philosophy is that it’s better to be approximately correct than precisely wrong. If you are trying to measure well-being from GDP, you might reach the wrong answer. Our methods are not as precise as GDP right now, but at least we’re directly measuring the things that we want to measure.

BRINK: Was there a wide range of results between the digital services?

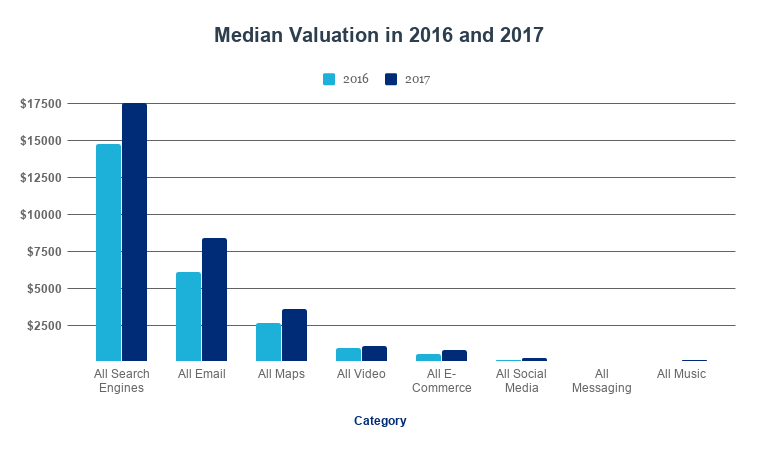

Mr. Collis: Before running the studies, I would have guessed social media would be much more highly valued than other digital goods. But what we found is that the most valued goods, by far, are search engines. Search engines generate almost $14,000 to $15,000 of revenue to the median consumer every year, which is really high. As opposed to social media, which seems to generate $400 to $500 of value every year. We also found maps were highly valued, around $3,000 of value a year.

Source: MIT Initiative on the Digital Economy

BRINK: Have you uncovered fluctuations in these prices over time?

Mr. Collis: We have been doing these studies since 2016, and what we found is that, for example, we see that the valuation for Facebook is falling a lot since 2016. This is not necessarily a result of the privacy scandals Facebook has had. In general, people just seem to value Facebook less and less over the past three to four years. And at the same time, we see valuations for Instagram and WhatsApp increasing, which are also owned by Facebook. So, some of the goods are falling while others are increasing.

It’s important to understand that we are only looking at the positive side of this. Another interesting research agenda would be to see if these digital goods are actually making us happy. These metrics are only measuring economic well-being, but some of these goods might not be great for people’s true happiness. So we should keep that in mind while looking at these results.