How the Middle Powers Are Determining Asia’s Power Balance

The chairman of the US Joint Chiefs of Staff, and the chief of the general staff of the Chinese People's Liberation Army shake hands after signing an agreement in Beijing. The U.S. and China are the two largest players in the area, yet middle powers will become more important in an age of great power competition.

Photo: Mark Schiefelbein/AFP/Getty Images

Tensions between nation states in the Asia-Pacific will have profound and uncertain implications for war and peace in the 21st century. The region is moving from an open and consensual order to one defined more by competition and zero-sum politics between the two largest players in the area, the United States and China.

The Shifting Distribution of Power

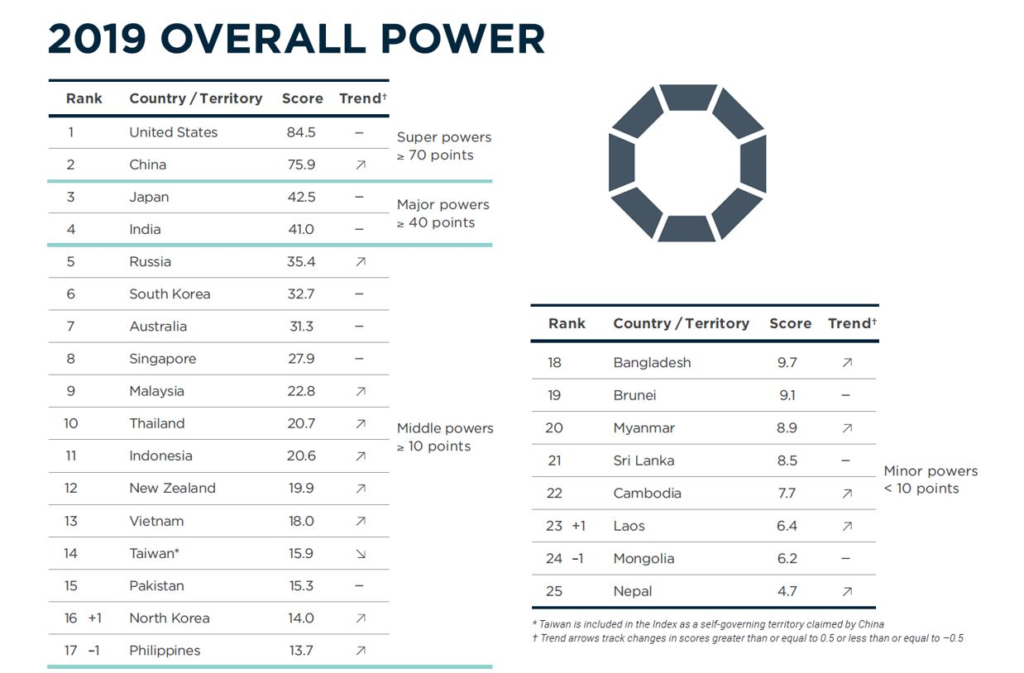

To make sense of these long-term trends, the Lowy Institute Asia Power Index is an analytical tool that tracks changes in the distribution of power in the region.

The Index ranks 25 countries and territories in terms of what they have, and what they do with what they have — reaching as far west as Pakistan, as far north as Russia and as far into the Pacific as Australia, New Zealand and the U.S.

The 2019 edition has been expanded to 126 indicators and evaluates state power across eight thematic measures: military capability and defense networks, economic resources and relationships, diplomatic and cultural influence as well as resilience and future resources.

There are three trends that emerge from this research that are set to shape the region in decades to come:

- Under most scenarios, the U.S. will not be able to halt the narrowing power differential between itself and China. Nor will Beijing simply grab the scepter of unipolarity off the Americans. It is increasingly likely that neither power will be able to exert undisputed primacy in Asia.

- Globalization will still involve the U.S. and China, even if the two become less dependent on each other. China is too enmeshed in the international system to be contained. There are fewer ideological compulsions and economic advantage counts for more than during the last cold war. Rather than choosing sides, pushback from countries in the region will be issue-specific and reflect varying national interest calculations.

- Far from being the hapless victims, middle powers will become more important in an age of great power competition. When two superpowers are gridlocked, the actions of the next rung of powers will constitute the marginal difference.

Indeed, major powers, such as Japan and India, along with middle powers in Southeast Asia, can work organically to forge a favorable — and preferably peaceful — balance of power in the region. However, balancing the sharpening ambitions of China and the fading predominance of the U.S. will require that these other countries more clearly align their interests.

It is not clear that this will be feasible. The countries in the region are separated by oceans, distinct geopolitical contests and legacies and vast demographic differentials representing young and old Asia.

2019 Overall Power in the Asia Power Index

The U.S. is Still the Dominant Military Power

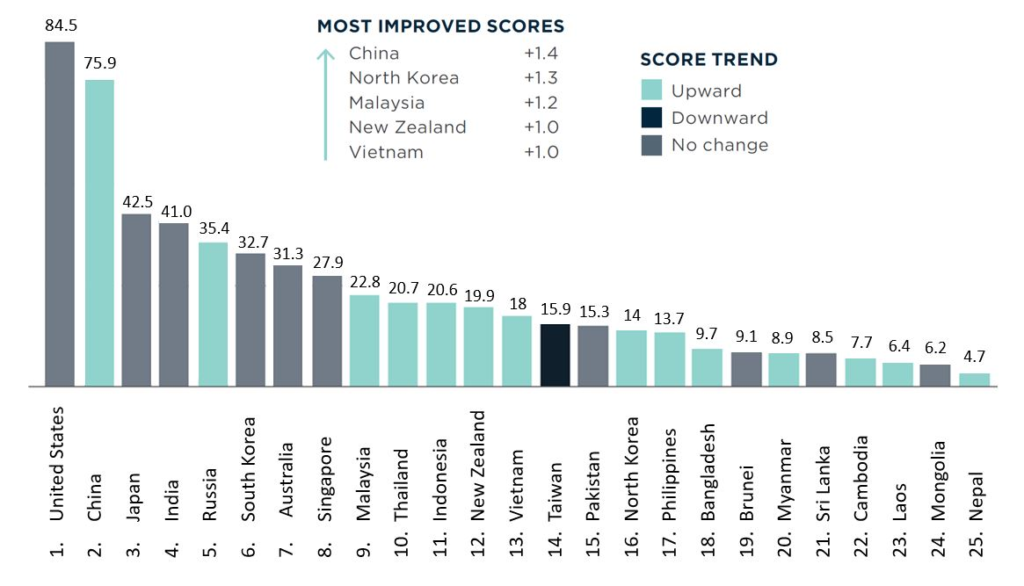

The U.S. claims the top spot in four of the eight Index measures and its overall power score — the only country to top 80 points — remains unchanged from last year.

America is still the dominant military power — reflected in the depth of its regional defense networks — as well as the most culturally influential power, as the leading study destination and source of foreign media in the region.

Nevertheless, the U.S. faces relative decline. A 10-point lead over China in 2018 has narrowed to 8.6 points in 2019.

The Trump administration’s focus on trade wars and on balancing trade flows one country at a time has done little to improve the glaring weakness of U.S. influence in its economic relationships. The obvious contradictions between Washington’s revisionist economic agenda and its role as a status quo power providing consensus-based leadership have contributed to its third-place ranking, behind Beijing and Tokyo, for diplomatic influence in Asia.

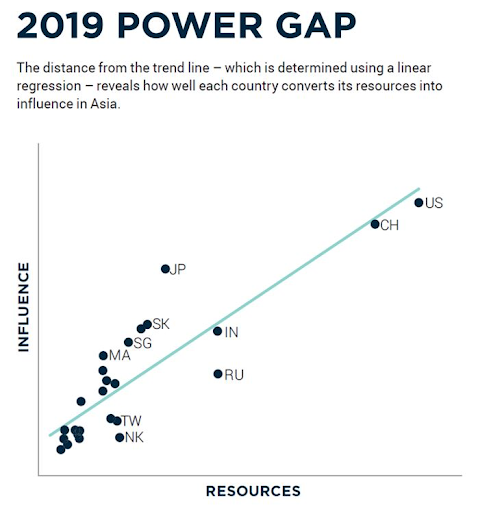

The U.S. has moved from a positive to a negative Power Gap in 2019, indicating it has become less effective at converting its resources into broad-based influence in Asia.

The Rise of China’s Domestic Markets

China, the emerging superpower, netted the highest gains in overall power in 2019, ranking first in half of the eight Index measures.

For the first time, China narrowly edged out the U.S. in the Index’s assessment of economic resources. In absolute terms, China’s economy grew by more than the total size of Australia’s economy in 2018. The world’s largest trading nation has also paradoxically seen its gross domestic product (GDP) become less dependent on exports. This makes China less vulnerable to an escalating trade war than most other Asian economies.

Access to Western markets will likely prove increasingly marginal to the global ascendancy of Chinese technology. The country’s consumer base is making large-scale implementation of new technologies, such as 5G, easier to achieve at home, before being rolled out into emerging markets.

Beijing has chosen to concentrate its military resources and modernization efforts on the near abroad in contrast to America’s global military posture and security commitments. Within its region, China’s defense budget is 56% larger than those of all 10 Association of Southeast American Nations (ASEAN) economies, Japan and India combined.

Despite steady advances, however, Beijing faces political and structural challenges that will make it difficult to establish undisputed primacy in the region.

Beijing’s hard power remains hobbled in key respects. China’s ninth place for defense networks still constitutes its weakest performance across the measures of power. As the People’s Liberation Army’s presence in contested spaces grows, so too do efforts by other powers to create a military and strategic counterweight in response. President Xi Jinping’s flagship Belt and Road Initiative faces growing degrees of opposition. In many cases — from Malaysia to Myanmar — this has resulted in renegotiations resolved in favor of the borrower.

Beijing also faces growing internal hurdles: China’s workforce is projected to decline by 158 million people from current levels in less than 30 years. This likely presages societal and economic challenges. By mid-century, China’s total population will also be approximately 20% smaller than that of India, a growing potential regional rival.

Not a Two Player Game

There is often a temptation to reduce the complexity of Asia’s international order to a two-player game. In fact, the Indo-Pacific ecosystem is sustained by a much wider array of actors.

Japan and India, the third and fourth ranked powers, are cultivating strategic ties with each other. Yet they are unlikely bedfellows. Unlike Japan, which operates within a U.S.-dominated alliance system, India will continue to cherish its strategic autonomy.

Japan is the quintessential smart power, using the country’s limited resources to wield a top-four ranking across the four influence measures. It finishes in the top two, only six points behind China, for diplomatic influence. Tokyo successfully resuscitated the Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP) in 2018, which became the TPP-11, together with 10 other economies minus the U.S.

Whereas Japan is an overachiever in long-term decline, India is an underachiever relative to both its size and potential. Despite Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s Act East Policy, New Delhi trails in sixth and eighth place for economic relationships and defense networks, respectively, and is down two places in diplomatic influence in 2019.

What India lacks in influence, it makes up for in scale. India’s economy is predicted to double in size and reach approximate parity with the U.S. by 2030. However, India will not be the next China. New Delhi lacks the control over the allocation of economic resources that has been intrinsic to China’s rise. Yet, as the giant grows in uneven and incremental steps, so too will its ambitions.

The Importance of Middle Powers

A diverse set of middle powers have made gains in their overall power in 2019. North Korea overtook the Philippines, now relegated to 17th place, registering the largest increase in its overall power score after China. The nuclear power jumped five rankings in diplomatic influence, albeit starting from a low twenty-first place, in the year following the first-ever meeting between the leaders of North Korea and the U.S.

Summit diplomacy in Singapore and Vietnam — ostensibly on equal terms with the U.S. — has elevated and partly normalized North Korea’s regional standing and ties. Pyongyang, however, remains a brittle power preoccupied by its survival. The risk of a lapse into further crises is high.

Malaysia has fared better in the last year across the Index’s influence measures, where it has resumed its standing among the top 10 most diplomatically influential powers in Asia. The return of Prime Minister Mahathir Mohamad has refocused the government’s attention on the bargaining power of middle powers. He has succeeded in obtaining more favorable terms for foreign-funded infrastructure projects while maintaining close ties to Beijing.

Malaysia offers a case in point of how Southeast Asia remains reluctant to choose sides between the U.S. and China. Instead, a more hazardous variant of globalization is being defined simultaneously by heightened competition and continued economic interdependence.

Remote New Zealand retains the most favorable strategic geography in the region, surrounded as it is by friends and fish. The same cannot be said of Vietnam or Taiwan, whose locations in contested waters south of China play directly into their strategic vulnerability. Vietnam has made rapid progress in military and economic spheres. Current trend projections place it tenth for future resources.

By contrast, Taiwan has become the only middle power in the Index to register a significant downward shift in overall power from 2018. The island — ranked 14th for overall power — presents a significant check on China’s aspirations to become a fully-fledged sea power. Taipei’s fall in power, however, betrays its geopolitical significance and reflects its position as a political outsider in Asia.