The Danger Lurking in the Hotter Cities of the Future

People visit Liberty Park in Lower Manhattan, in New York City. Liberty Park, elevated above Liberty Street in Lower Manhattan, overlooking the National September 11 Memorial Plaza and One World Trade Center.

Photo: Drew Angerer/Getty Images

With more people living in cities than ever before, cities can no longer ignore the deadly combination of urban heat and climate change. As the world continues its inexorable march of warming, the risks will keep escalating for cities.

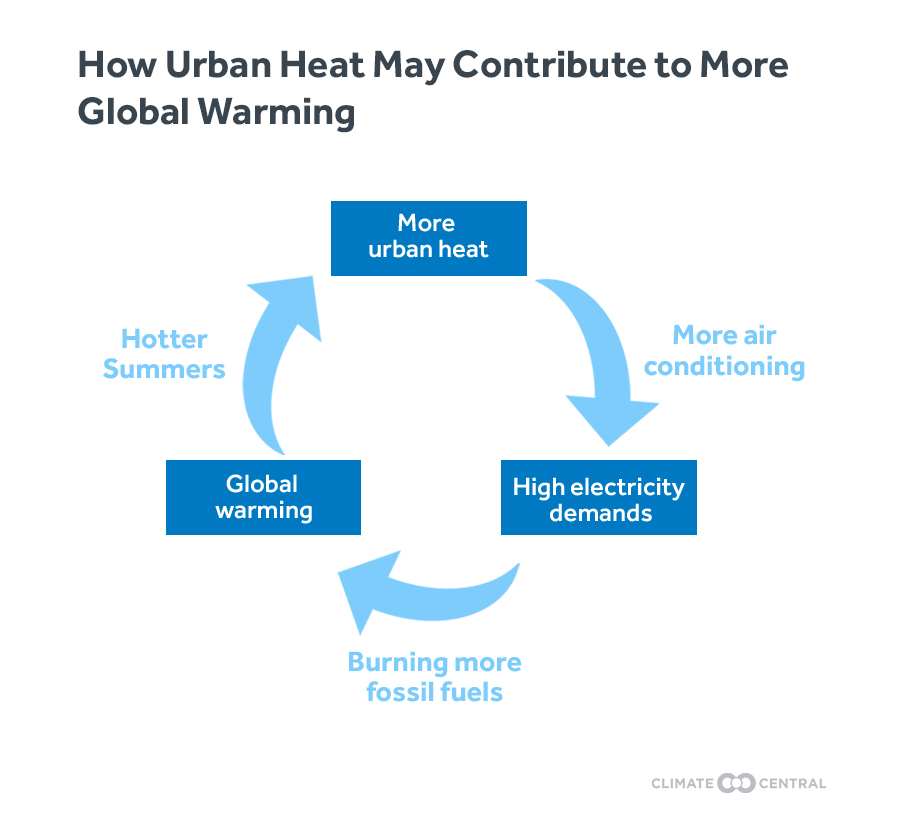

The young and old living in urban centers will be vulnerable to health issues from extreme heat and the smog it helps generate; the power grid will be pushed to the limit by an ever-increasing demand for air conditioning; and hotter cities will actually perpetuate a vicious cycle of greenhouse gas-driven global warming.

The dog days may be symbolic of American summers, but the intense heat of 2016 is a sign of the dangerous heat on the rise in cities. In the midst of 2016’s record-breaking global heat, seven states in the U.S. had their hottest August on record. Cities like Boston, Philadelphia, and Washington, D.C., suffered through unprecedented numbers of days above 90 degrees and elevated levels of nighttime heat.

Since the first half of the 20th century, the U.S. has had more people living in its cities than in rural areas, and since 2000, more than three quarters of Americans reside in cities. To meet this demand, cities have grown both up and out. They don’t just have more people; they have more buildings, more cars, and more machines, all of which create heat. Cities also have more cement and asphalt, which hold in more heat than plants and grass. Combined, these changes have created urban heat islands—areas in and around cities where temperatures are measurably hotter than in nearby rural areas.

U.S. cities see an average of about eight more days each summer with temperatures above 90 degrees F (32 degrees C) than nearby rural areas. Some cities see a lot more than that. Dallas, Denver, Louisville, Las Vegas, and Nashville are among the cities that typically see at least 20 additional 90-degree days each summer. And of course, single days can see much bigger differences. Some days can be 20-25 degrees F hotter in urban areas compared to rural communities in the same region.

Urban heat islands are often more intense at night, when the hot surfaces in cities—roads, sidewalks, and rooftops—hold on to the daytime heat a lot longer.

Of course, it’s not just cities that are getting warmer. Global temperatures are about 2 degrees F hotter now than during preindustrial times. Billions of tons of greenhouse gas emissions—the majority being carbon dioxide coming from burning of fossil fuels—are driving this climate change. The U.S. has seen a similar trend toward hotter temperatures over the past century, with warming accelerating since 1970.

That means cities are getting hotter on top of warming happening across the country.

In fact, hotter cities may actually be reinforcing global warming: when summer temperatures spike in cities, tens-to-hundreds of thousands of buildings run air conditioners. Those air conditioning units blow hot air outside, driving up temperatures in their immediate vicinity. What’s more, running all those air conditioners consumes electricity, and in the U.S. most power is still generated by burning coal and natural gas. The carbon dioxide emissions from power plants go into the atmosphere and help contribute to even more global warming.

As extreme summer temperatures become more common in the densely populated Northeast and Midwest, more Americans than ever before are relying on air conditioners. Last August, for example, the record-breaking heat drove temperature-related energy demand to its second-highest level ever.

Extreme heat is also a threat to the power sector. When electricity demand spikes unexpectedly, it can overwhelm the power grid. Power companies may then end up negotiating with customers to dial down their power needs during peak times—usually in the mid-to-late afternoon. At the worst—though this happens rarely in the U.S.—these surges in demand force power companies to issue rolling blackouts, where they stop delivering electricity to all customers at the same time. Right at the time when people need air conditioning the most, we are at risk of not being able to access it.

Just as critical, extreme heat exposure also poses serious health risks. Heat is already the No. 1 weather-related killer in the U.S., according to the National Weather Service. In an average year, heat waves and extreme temperatures kill more people than tornadoes, hurricanes or floods. Hot weather threatens the very young and the very old, who tend to have more difficulty regulating body temperatures. And socially vulnerable groups, like those living below the poverty line, are particularly vulnerable because they are less likely to have access to air conditioning.

Summer heat also exacerbates air quality problems already inherent to most cities. Pollution from cars and power plants, combined with hot weather, creates ground-level ozone, the main component of smog. Ozone is responsible for most air pollution-related health impacts in the U.S. and is estimated to be responsible for thousands of premature deaths every year.

The risks are only increasing. If global greenhouse gas emissions continue increasing at their current rates, our summers are going to get even hotter. Today, Chicago and New York average one or two days each summer with temperatures above 95 degrees F. But by 2050, they are projected to see 15-25 days above 95 degrees F every year until 2060—and 40-50 days by the end of this century. Southern cities, such as Dallas, that see an average of 10-15 days above 100 degrees F each summer today could see more than three months of 100-degree-plus weather each year by 2100.

Fighting Urban Heat Islands

There are things cities can and are doing to help reduce urban heat islands. Building green spaces—including parks, grassy and tree-lined boulevards, and even garden-topped roofs—helps lower temperatures. Trees can provide more shade, and plants can help cool the air as water evaporates from leaves and soil. Miami, for example, has a city-wide landscaping ordinance, requiring new buildings to have plants surrounding them.

There are also “cool roof” materials builders can use to help deflect the heat from buildings, instead of absorbing it. Many cities—Sacramento, California, for example—have programs in place that offer rebates for buildings that incorporate these cool-roof technologies.

But even with these measures, the risks from urban heat can’t be eliminated entirely. Rising global temperatures will continue to drive extreme heat, and cities need to be prepared for potentially dangerous heat waves.

Cooling centers distributed throughout cities can provide much needed relief for people who don’t have air conditioning. And warning systems can help people prepare for heat waves in advance. Philadelphia was the first U.S. city to begin issuing heat-advisory notices. And as part of the city’s heat and health watch warning system, they’ve appointed thousands of block captains that are responsible for checking on neighbors in the midst of a heat wave.

As America’s cities continue to grow, we can’t afford to ignore the cumulative impacts of urban heat and global warming. Cities can better prepare themselves and their residents for heat waves, and increase the overall awareness of the hazards of urban heat islands. But the risks will persist unless global greenhouse gas emissions are also dramatically reduced.

As more and more people move into U.S. cities, rising temperatures from human-driven climate change will threaten their health and livelihoods. Local initiatives can’t completely eliminate the impacts people and infrastructure will suffer if cities keep getting hotter in the coming decades.

Stopping, and potentially reversing, the current global warming trend is a critical step toward making our cities safer and less vulnerable to the threat of extreme heat.