The Implications of the US-China Trade War on Asia

Containers are seen at a port in Lianyungang in China's eastern Jiangsu province. A narrative is building that countries in Southeast Asia will be able to benefit from an all-out trade war between the U.S. and China.

Photo: STR/AFP/Getty Images

U.S. trade protectionism has escalated through 2018—with an increasing focus on China. The U.S. so far has imposed tariffs on $250 billion of imports from China, to which China has responded with tariffs of its own on $110 billion of U.S. imports. The meeting between President Donald Trump and President Xi Jinping in early December has led to a truce, but there is a high risk that frictions will rumble on after the 90-day tariff freeze ends, if not before. A trade war between the two economies is a lose-lose proposition for the world economy and especially for Asia, which is home to some of the most open economies in the world.

However, multinational corporations are nimble, and at a more granular level, there are likely to be some companies, industries and possibly even small economies that benefit from the ongoing trade war. Daniel Gros, director of the Centre for European Policy Studies, recently suggested that the EU could be the big winner from a long U.S.-Sino conflict, citing the old adage, “when two quarrel, the third rejoices.”

Import Substitution and Production Diversion

A narrative is building that countries in Southeast Asia will be able to benefit from an all-out trade war between the U.S. and China. For example, an October 15 Bloomberg report, citing both companies and academics, used such quotes as “This [China-U.S. trade war] is better than the Trans-Pacific Partnership for Vietnam. …Vietnamese furniture [and] apparel industries are poised to increase market share in U.S.,” and “Thai seafood companies reeling in Chinese customers who want substitutes.” On October 25, The Economist wrote that “Wealthier countries are eyeing some of the high-end manufacturing that they lost to China. Taiwan is trying to lure back computer companies, while Malaysia and Thailand want to expand their footholds in electronics. In low-income countries, the focus is on the cheaper sectors that China has long dominated. Vietnam is strong in food processing; Cambodia in footwear; Bangladesh in clothing.”

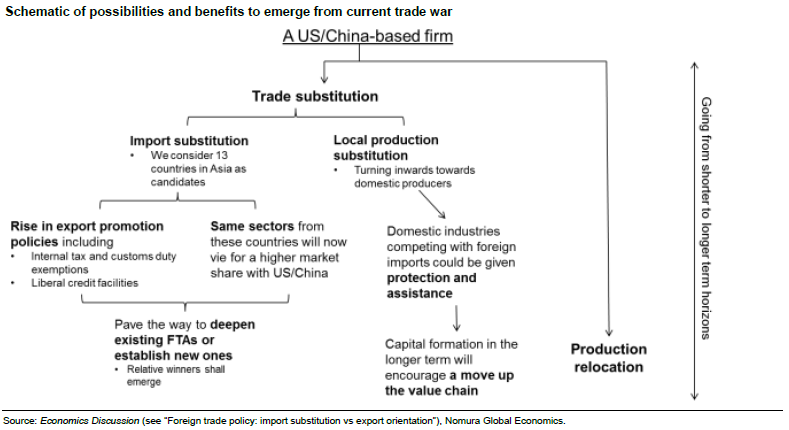

We quantitatively test these anecdotes by analyzing 7,705 products on the U.S. and China tariff lists. Two channels of potential benefit from this trade war are identified: import substitution (in the short term) and production relocation (in the medium term). How some countries—and more pertinently, companies and certain industries within countries—can benefit from the trade conflict is largely due to these two channels.

In the short term, if the U.S. and China charge higher tariffs on each other’s imports, then companies in the two countries will have an incentive to replace these now expensive imports with local production sources or substitute from other countries.

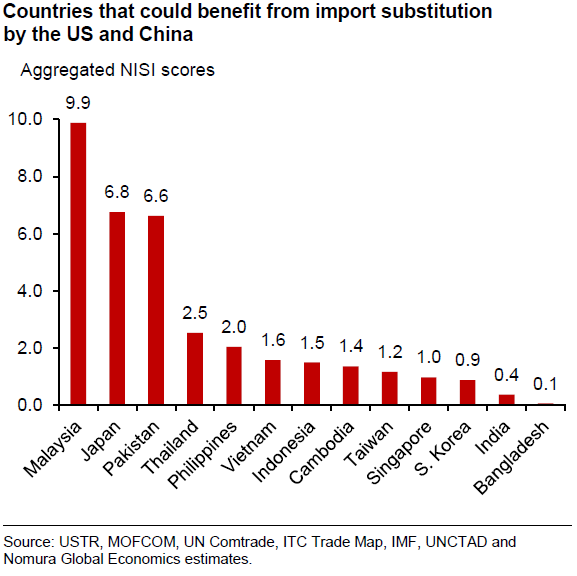

It is likely that Malaysia will emerge as the biggest beneficiary of import substitution by companies in China and the U.S., followed by Japan, Pakistan, Thailand and the Philippines. Of the 13 countries, Bangladesh, India and South Korea stand out as the least likely to gain on a relative basis in terms of import substitution. Our analysis shows that the biggest benefit to Malaysia is likely to come from electronic integrated circuits, liquefied natural gas and communication apparatus. For others, there is usually one leading product: “Vehicles with only spark-ignition internal combustion reciprocating piston engines” in Japan, cotton yarn in Pakistan, “units of automatic data processing” in Thailand and “electronic integrated circuits” in the Philippines.

Meanwhile, a prolonged U.S.-China trade conflict, in the medium term, would encourage multinationals to start diverting some of their production to factories in other countries to escape tariffs or even relocate entire manufacturing processes if the trade war continues.

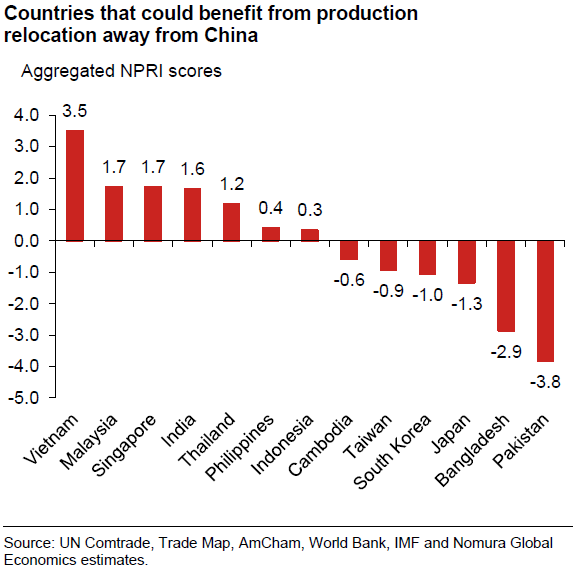

From a diversion of production and FDI perspective, our findings show that in the medium term, Vietnam is the Asian country that will benefit the most, followed by Malaysia, Singapore, India and Thailand.

Nimble Companies Have Been Quick in Identifying Opportunity

Globalization has led to an explosion of multinationals operating around the word, resulting in increasingly fragmented global supply chains. China sits at the center of this global goods trade network. Indeed, it makes little sense to refer to “Chinese exports” given that last year, 43 percent of China’s exports were produced by foreign-invested enterprises in China.

Economists tend to consider FDI to be slow-moving and sticky, but multinationals, often aided by new technologies, are much more nimble than they are sometimes given credit for. For example, in January 2018, when the U.S. imposed anti-dumping duties on washing machines manufactured in China, this did result in a decline in China’s exports of washing machines to the U.S.—but its washing machine exports to other countries remained strong. At the same time, South Korean multinationals were prompted to shift their washing machine production from China to Vietnam and Thailand, allowing them to grow their market share in the U.S.

Looking for Winners in Asia—Certain Caveats

Irrespective of any positive substitution effects, Asian countries are large suppliers of parts and components to China that are then assembled into exports, for which the U.S. is a major final destination. Asian economies indirectly face large negative impacts from higher U.S. import tariffs on China. Largely because of Asia’s elaborate supply chain—which so often ends at China—Asia, as a region, is likely to be a loser in a full U.S.-China trade war scenario.

Once scaled by GDP of the country of origin, eight of the 10 largest contributors of value-addition to China’s gross exports are Asian, namely Taiwan at 6.3 percent of its GDP, followed by Malaysia (4.1 percent), South Korea and Hong Kong (3.2 percent), Singapore (3.1 percent), Vietnam (2.8 percent), Thailand (2.5 percent) and the Philippines (2.3 percent).

Asia is also a large exporter of capital goods and could therefore be heavily affected if rising protectionism causes more companies globally to delay their investment plans. If China responds by depreciating the RMB, other Asian countries that have export structures similar to China’s could face greater competition, while China’s own purchasing power to buy imports from the rest of the region would be dented.

On the other hand, in the longer run, winners in Asia may emerge at a more macro level if the U.S. continues to turn inward and China fills the void by taking a greater leadership role in currently negotiated regional free trade agreements and revamping the Belt and Road Initiative, its multitrillion dollar overseas infrastructure initiative.