U.S.–China Trade War: What’s in It for Europe?

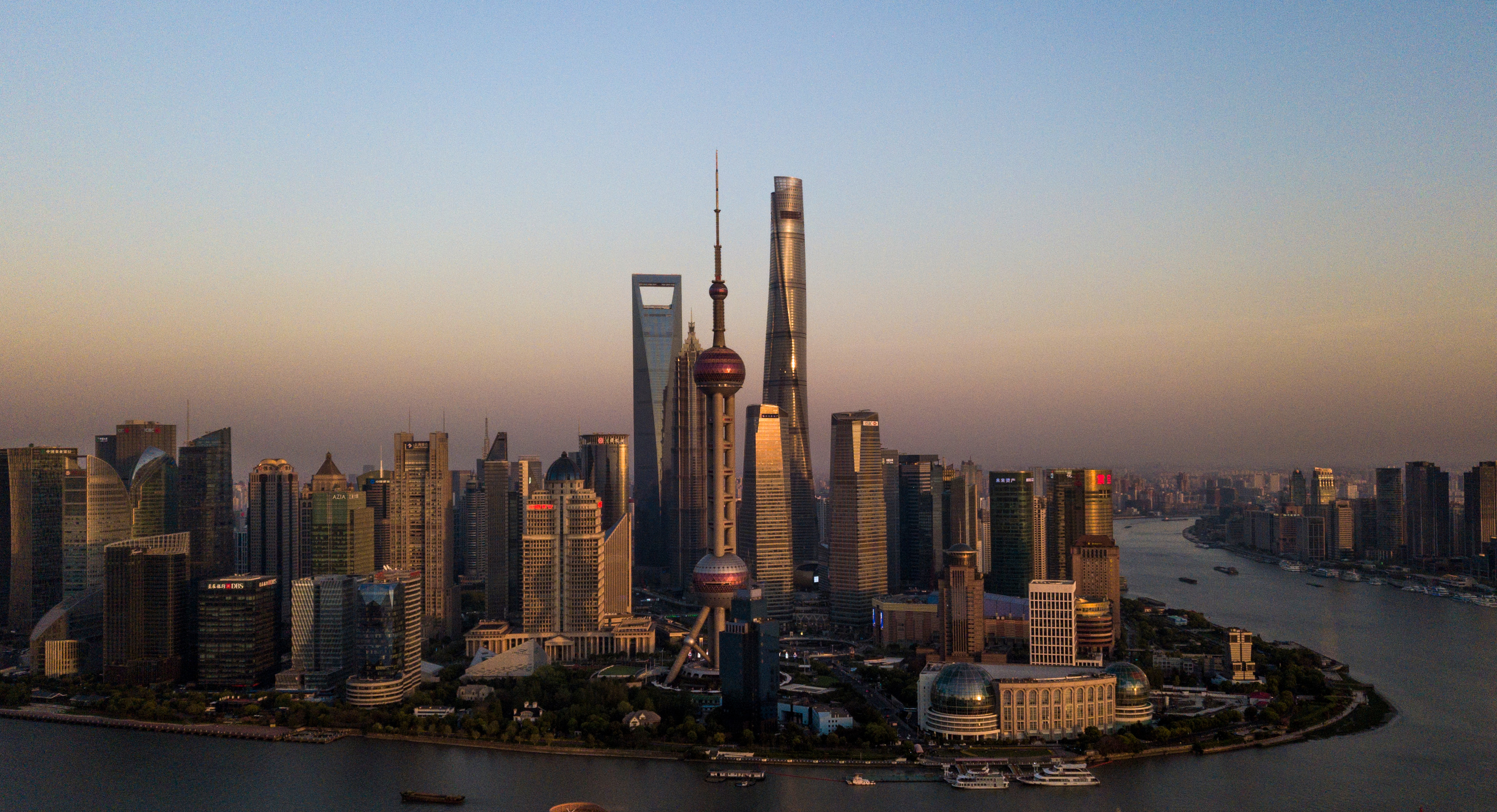

The financial district of Shanghai is pictured in the spring of 2018. Experts are keeping an eye on China-U.S. relations as the U.S. raises the stakes in a developing trade war.

Photo: Johannes Eisele/AFP/Getty Images

When the U.S. kicked off 2018 by imposing tariffs on solar panels and washing machines, it was not expected the trade disputes would escalate into a full-fledged war. However, such optimistic sentiments in the market have dissipated since mid-June.

The escalation of the trade war has caused an abrupt fall across various stock markets, especially in China. Shanghai Composite fell nearly 8 percent after China retaliated to the U.S. tariffs on $50 billion worth of Chinese products, which the Trump administration later escalated to be a $200 billion list. Emerging market currencies are also under huge depreciation pressure from capital outflows.

To help evaluate whether the market response is warranted or exaggerated, we measured the trade impact of additional import tariffs based on standard economic theory, namely two key parameters—the tariff pass-through rate and the price elasticity of demand.

On that basis, we estimate that, with the 25 percent of import tariffs, the expected increase in import tariffs could hover around 5 percent, while the reduction in import volume could reach 20 percent. This is equivalent to a net reduction of about 15 percent in import value, or a maximum loss of $5 billion (15 percent of $34 billion). Furthermore, the direct impact could even be smaller due to trade rerouting and substitution by third countries.

The New Normal: Reactive Markets

While the direct impact seems small, one should not forget that financial markets react to expectations of an additional escalation of a trade war, let alone a full-fledged technology arm race, which would bring even more uncertainties to the world. Hence, it is time to embrace the “new normal,” where markets react to negative expectations of limited immediate impacts of a trade war.

The end of multilateralism seems clear, at least for trade. However, one should also bear in mind that the world is no longer flat. Beyond trade, the U.S. is also building up barriers to flows of investment, knowledge and talents. For example, the U.S. has ratcheted up its efforts to vet China’s investments, especially those into U.S. high-technology companies. The most obvious instrument has been the Committee on Foreign Investment in the United States, a large part of whose actions have targeted China and especially the manufacturing and industrial sectors. In addition to investment, the U.S. could restrict the flow of talent and knowledge via tightening student/working visa issuance to Chinese citizens.

The end of multilateralism seems clear, at least for trade. However, one should also bear in mind that the world is no longer flat.

Implications for Europe

As the U.S. raises the stakes at the negotiation table, it is hard to imagine how China can accommodate the demands from the U.S. It seems that China does not have many effective ways to retaliate without hurting its long-term development. The best strategy it can take is to continue to open itself to the rest of the world. Because the EU is the largest economy outside the U.S., we should expect China to be much more willing to collaborate with Europe in the future and accept some of the EU’s longstanding requests on China to move further in their economic cooperation, namely better market access and reciprocity.

Within this context, the impact of what we considered to be a paradigm shift in terms of U.S.–China economic relations could potentially benefit the European Union, which heavily depends on a number of general and sectoral factors. For the general consideration, the key is the response of the EU Commission (i.e., whether it will align with the U.S. to protect its market from Chinese exports, or will maintain neutral policies). In the latter case, Europe could substitute the U.S. and China in each other’s markets to some extent. At a more granular level, the situation is clearly very different across sectors.

At the first glance, the U.S. and EU’s exports to China are very similar. China’s top five imports from the U.S. are chemicals, transport equipment, motor vehicles and medical instruments. China’s top five imports from Europe are motor vehicles, machinery and equipment, chemicals, medical instruments and transport equipment. If the EU does not take sides and the U.S. does not hit the EU directly, European industries’ potential market is quite relevant for motor vehicles and aircraft sectors—and more to come from the list of tariffs on the $200 billion worth of products.

If we assume that the EU could take up all the market shares of the U.S. and China in the counterparties’ market, potential gains for European exporters are huge. Based on the lists released by both parties in April, we find that European auto manufacturers have the most to gain in both the U.S. and China markets. Chemical products and machinery are the sectors that could potentially benefit from the tariff measures by the U.S. As for the gains in China’s market, European aircraft manufacturers are more likely to realize the gains as they do not face major competition from the other countries. Although China removed aircrafts from the list of products subject to tariffs released in July, European aircraft manufacturers are better positioned to enjoy the benefits if China decides to escalate.

For the U.S. tariffs on an additional $200 billion worth of Chinese imports released on July 10, European manufacturers of consumer goods are expected to grasp the opportunity and expand their market share in the U.S. market. Noticeably, European exporters have the capacity to expand their market share as they already take up great shares in the global market for many products. The EU now supplies more than 40 percent of global imports for furniture, metal, plastic and paper products.

Which Sectors Benefit?

To more accurately quantify the benefits at a sectoral level, we constructed a Trade Complementarity Index. The sector benefiting the most is the semiconductor industry, which could potentially expand its exports more than three times its current exporting value. However, when the relative size in the EU’s export structure is taken into account, the most relevant gains occur in motor vehicles, aircraft/spacecraft and chemical products, with the maximum potential gains reaching 24 percent, 66 percent and 17 percent of their current exports. The benefits for the other sectors vary with their sizes and potential gains. For example, the semiconductor sector can potentially expand by as much as 3.57 times its current exporting value, whereas iron and steel only see a marginal benefit of 21 percent of its current exports at maximum.

Another important finding of our analysis is that the potential export gains are larger in the U.S. market. In other words, within the sectors that the EU already exports, the substitution of China’s exports to the U.S. accounts for 68 percent of total potential gains (equivalent to $69 billion). The China market, instead, offers a potential gain of up to $32 billion to the European exporters (as far as the substitution of U.S. products is concerned). The takeaway of this is that European exporters benefit more from U.S. sanctions on China than from China’s retaliation. Of course, such sectoral gains can be wiped out if U.S. imposes import tariffs on Europe.

We should note, however, that no due care has been taken with the complexities of the value chain in this analysis, which makes our results less obvious for goods of which components are produced in the U.S. and/or China (rather than being vertically integrated within the European production chain). Also, if China were to accept the U.S. demand and expand its imports from the U.S., European sectors heavily dependent on exporting to the Chinese market would be severely affected.

In sum, our analysis suggests that Europe should benefit from the U.S.–China trade war. This is especially the case for those sectors that can substitute the U.S. or Chinese exports into China and the U.S., respectively. As long as Europe does not meddle in the U.S.–China frictions, the most obvious winning sectors would be motor vehicles, aircrafts, and chemical products.