What Happens to Australia’s Plastic Waste?

Residents of Happy Land village collect and recycle plastic waste as a means of living in Manila, Philippines. Southeast Asia has become the new destination for Australia’s recycled plastics since China imposed strict conditions.

Photo: Jes Aznar/Getty Images

Last year, many Australians were surprised to learn that around half of our plastic waste collected for recycling is exported, and up to 70 percent is going to China. So much of the world’s plastic was being sent to China that China imposed strict conditions on further imports. The decision sent ripples around the globe, leaving most advanced economies struggling to manage vast quantities of mixed plastics and mixed paper.

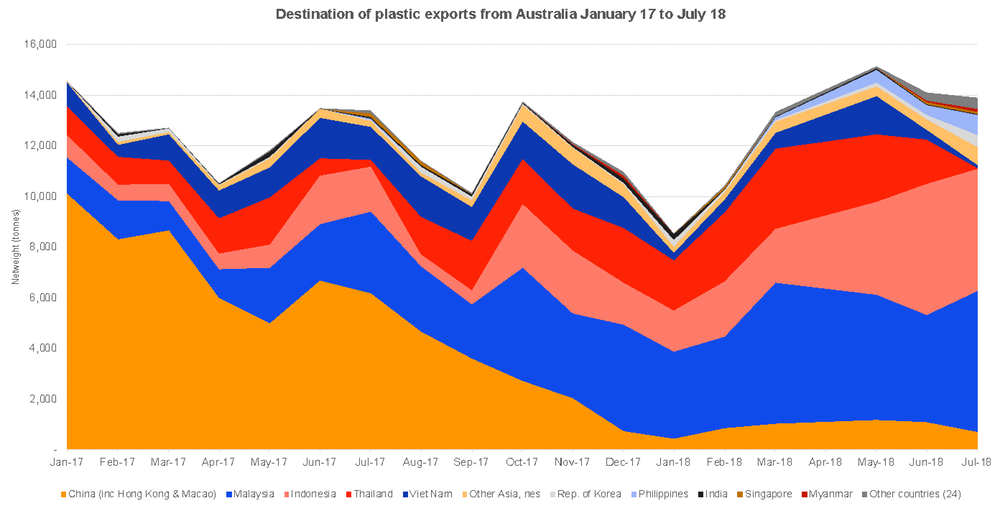

By July 2018, which is when the most recent data was available, plastic waste exports from Australia to China and Hong Kong reduced by 90 percent. Since then, Southeast Asia has become the new destination for Australia’s recycled plastics, with 80-87 percent going to Indonesia, Malaysia, Thailand and Vietnam. Other countries have also begun to accept Australia’s plastics, including the Philippines and Myanmar.

But it looks like these countries may no longer deal with Australia’s detritus.

In the middle of last year, Thailand and Vietnam announced restrictions on imports. Vietnam announced it would stop issuing import licenses for plastic imports, as well as paper and metals, and Thailand plans to stop all imports by 2021. Malaysia has revoked some import permits, and Indonesia has begun inspecting 100 percent of scrap import shipments.

Why Are These Countries Restricting Plastic Imports?

There are serious environmental and labor issues resulting from the way the majority of plastics are recycled. For example, in Vietnam, more than half of the plastic imported into the country is sold to “craft villages,” where it is processed informally, mainly at a household scale.

Informal processing involves washing and melting the plastic, which uses a lot of water and energy and produces a lot of smoke. The untreated water is discharged to waterways, and around 20 percent of the plastic is unusable, so it is dumped and usually burnt, creating more litter and air quality problems. Burning plastic can produce harmful air pollutants such as dioxins, furans and polychlorinated biphenyls, and the wash water contains a cocktail of chemical residues, in addition to detergents used for washing.

Working conditions at these informal processors are also hazardous, with burners operating at 260-400 degrees Celsius. Workers have little or no protective equipment. The discharge from a whole village of household processors concentrates the air and water pollution in the local area.

Before Vietnam’s ban on imports, craft villages such as Minh Khai, outside of Hanoi, had more than 900 households recycling plastic scraps, processing 650 tons of plastics per day. Of this, 25-30 percent was discarded, and 7 million liters of wastewater from washing was discharged each day without proper treatment.

These plastic recycling villages existed before the China ban, but during 2018, the flow of plastics increased so much that households started running their operations 24 hours a day.

The rapid increase in household-level plastic recycling has been a great concern to local authorities, due to the hazardous nature of emissions to air and water. In addition, this new industry contributes to an already significant plastic litter problem in Vietnam.

Green Growth or Self-Preservation?

A debate is now being waged in Vietnam over whether a green recycling industry can be developed with better technology and regulations, or whether they must simply protect themselves from this flow of “waste.” Creating environmentally friendly plastic recycling in Vietnam will mean investment in new processing technology, enhancing supply chains, and improving the skills and training for workers in this industry.

Engineers at the Vietnam Cleaner Production Centre have been working on improving plastic processing systems to recycle water in the process, improve energy efficiency, switch to bio-based detergents and reduce impacts on workers. However, there is a long way to go to improve the vast number of these informal treatment systems.

What Can We Do in Australia?

While Australia’s contribution to the flow of plastics in Southeast Asia is small compared to that arriving from the U.S., Japan and Europe, we estimate it still represents 50-60 percent of plastics collected for recycling in Australia.

Should we be sending our recyclables to countries that lack capacity to safely process it and are already struggling to manage their own domestic waste? Should we participate in improving their industrial capacity? Or should we increase our own domestic capacity for recycling?

While there may be times it makes sense to export our plastics overseas where they are used for manufacturing, the plastics should be clean and uncontaminated. Processes should be in place to make sure they are recycled without causing added harm to communities and local environments.

Australia and other advanced economies need to think seriously about the future of exports, our own collection systems and our “waste” relationships with our neighbors.

This piece first appeared in The Conversation.