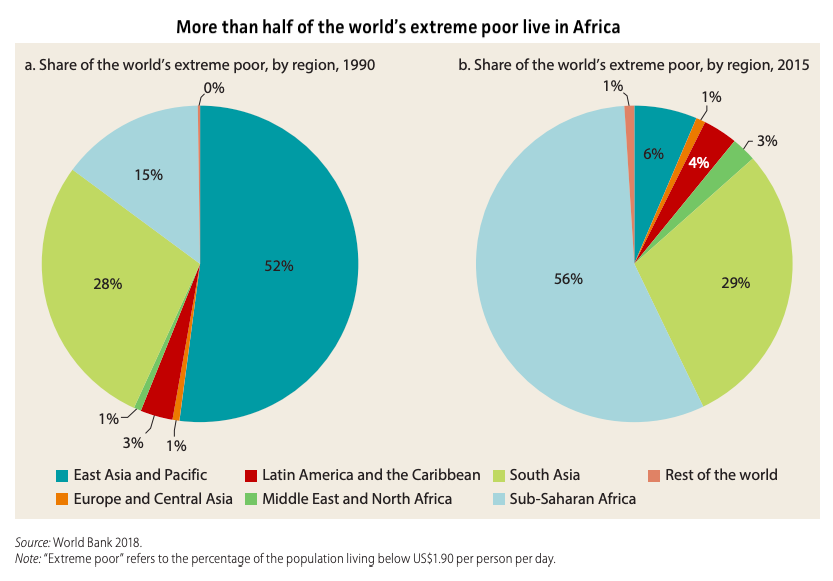

An image of Johannesburg, South Africa. The rate of extreme poverty in Africa remains persistently high at 41% — compared to a global average of 10%.

Photo: Shutterstock

The latest World Bank research shows that the rate of extreme poverty in Africa remains persistently high at 41% — compared to a global average of 10%. Without improvement, this could disrupt global growth.

BRINK talked to Louise Fox, a nonresident senior fellow in the Africa Growth Initiative for the Global Economy and Development Program at the Brookings Institution, about how corporations can help Africa eradicate extreme poverty while pursuing business interests there.

BRINK: Most of us understand the moral imperative to help eradicate extreme poverty around the world. From a business perspective, however, why should companies outside of Africa be concerned with extreme poverty on the continent?

Louise Fox: Today, most companies produce goods through global value chains and sell their products worldwide. Extreme poverty is a threat to both. First, increased exports from the United States to developing countries was key to pulling us out of the major recession of 2008, and much of the future growth in demand for rich-country exports is expected to come from the developing world.

However, poor people can’t afford the goods and services that the U.S. produces, so the U.S. needs a global middle class in order to sell its products.

Second, countries with a lot of extreme poverty are more fragile politically as well. We have seen how civil conflict can disrupt or destroy key inputs companies need for production, including agricultural products such as cocoa (for chocolate manufacturing), avocados (for guacamole) or minerals such as copper or the rare-earth ones.

Finally, many countries in Asia are aging. Africa is where the global workforce that U.S. companies will need is growing. But production can only move to Africa if Africa’s workforce is ready: educated and healthy. Poverty prevents this human capital from being developed.

BRINK: What role can companies outside of Africa play in helping support and drive employment and wage growth?

Ms. Fox: Foreign direct investment is a great idea, and that can be in agriculture or in nonagricultural sectors. FDI is rising in Africa as an important source of jobs, both from the West and from China, in both industry and services. And I think it’s important that it continues to rise. It works really well when foreign firms can find local partners and work with them. That also helps to transfer technology, know-how, management skills, et cetera, to local partners. That was very important in the growth of manufacturing in East Asia.

BRINK: What does local partnering like this look like in practice?

Ms. Fox: In the agricultural sector in West Africa, Nestlé has been helping to structure the value chain around cornmeal so that they can produce a porridge for kids with local grain. They are trying to structure the value chains for the cornmeal from the farm and improve the way they harvest it and store it so that it doesn’t get fungus. So the millers are now producing the high grade that Nestlé needs, and then Nestlé produces the porridge there. Previously, they were importing grain from elsewhere to produce the porridge.

There are Chinese firms also working with local partners in manufacturing, especially things like building materials, which are heavy, so it’s good to manufacture them where you’re going to need them.

And you have South African and European winemakers investing in Ethiopia because they have a good climate for grapes. They’re not making enough to export right now; they’re just sort of feeding the high-end tourist market. That’s an example of a new business that people might not be thinking of.

BRINK: You’ve studied women’s economic empowerment in Africa. How can foreign investors support gender equality in the workplace and overcome rigid gender norms around what jobs women can hold?

Ms. Fox: Foreign managers may be comfortable with women in certain roles. That’s especially true in things like foreign banks. We know that foreign banks are more likely to employ more women than domestic banks. In addition, foreign companies make a lot of products that women need (feminine hygiene and contraceptives), and they often train women to sell them to other women.

I visited this (cattle) farm in Ethiopia (run by a consortium of international partners), and the manager of the whole feedstock operation was a woman. And I said, “Wow, how did that happen?” And they said, “We were looking for a manager, and she was the best one. And actually, at the time we promoted her to manage the whole operation of buying the feed and blending it, some of the elders in the community came and told us we shouldn’t do it. And we told them we had to do it because she was the best qualified.” Now you find other businesses that don’t necessarily make that effort. It really depends on the business.

Some countries are making a big effort on educating girls and young women, and that’s making a big difference. What you see in some countries like Tanzania is if they get into secondary school, young women are more likely to finish secondary school than males. And parents are beginning to see that as a good investment.

BRINK: The level of global extreme poverty was 10% in 2015, compared to 41% for Africa. Why is Africa lagging so far behind the rest of the world?

Ms. Fox: There are two reasons why Africa is lagging behind. First, their rate of population growth is higher. So that means that while there’s good GDP growth, there’s lower per capita growth. Second, there was such high initial poverty in the region at the beginning of the 1990s, there was such poor access to public services, human capital development services and such, and high levels of infant mortality. So that basically limited the ability of households to participate in growth. When compared with other equally poor countries in other regions, African countries have not been less effective at converting per capita household income growth into poverty reduction.

BRINK: What will it take to lower the poverty level in Africa to help meet the U.N.’s goal of eradicating extreme poverty by 2030?

Ms. Fox: There are so many unknowns. If there’s one thing that can stop poverty reduction, it’s civil wars and regional wars, and that whole situation seemed to be calming down, but then it flared up again. Over the next 15 years, if fertility declines substantially, households are going to invest in the quality of their children better, and the public sector can invest in the quality of those children through better education and health systems. And that would make a big difference.