As Global Protectionism Rises, Japan Emerges as Asia’s Free Trade Champion

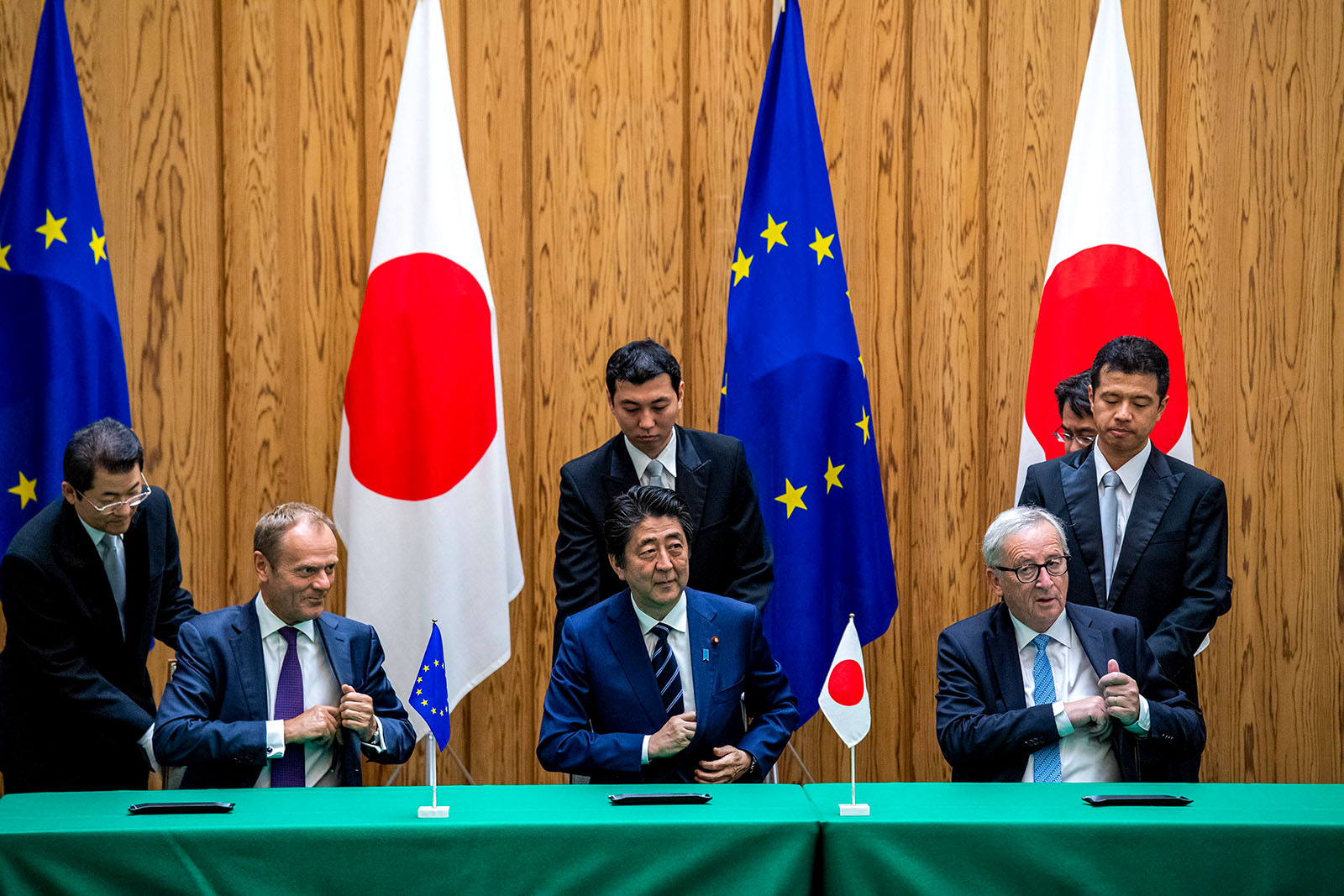

Japanese Prime Minister Shinzo Abe (C) signs an agreement with European Council President Donald Tusk (L) and European Commission President Jean-Claude Juncker (R) at the Prime Minister's Office in Tokyo on July 17, 2018. Japan is now emerging as Asia's new champion for free trade and investment.

Photo: Martin Bureau/AFP/Getty Images

In a world economy seemingly threatened by protectionism, Japan is now emerging as Asia’s new champion for free trade and investment through the Comprehensive and Progressive Agreement for Trans-Pacific Partnership and the EU-Japan Economic Partnership Agreement.

The 1980s Are Long Past

Japan’s high-growth period, from the end of World War II until the early 1990s, was substantially driven by exports of motor vehicles and electronics. But these exports were fostered by protectionist policies that restricted imports into Japan and promoted exports.

The U.S. government, the major destination for Japanese exports, tolerated this situation for a long time, as Japan was its key Asian ally during the Cold War. Western attitudes changed during the 1980s, however, as Japan racked up large trade surpluses and appeared to become a rival of the U.S. Japan was then pushed to open its markets and invest in Western markets. Further opening of Japanese markets was achieved through the Uruguay Round of trade talks from 1986 to 1993.

Despite these measures, Japan remained a very protected market for foreign investment and international trade. For example, the accumulated stock of foreign direct investment in Japan represents only 4 percent of GDP, a figure that has barely budged over recent years.

This is in sharp contrast to the EU and the U.S., where inward FDI represents some 55 percent and 36 percent of GDP, respectively. And while foreign investments have enormous difficulty cracking the Japanese market, Japanese investors are very active globally with the stock of outward FDI, amounting to 31 percent of GDP.

Over two decades of economic stagnation inspired the current Japanese government to launch a reform program in 2013, dubbed “Abenomics” after Prime Minister Shinzo Abe, to revitalize the economy. This is of critical importance to the future of Japan, with its rapidly aging population and with labor productivity more than 25 percent below the top half of OECD economies.

Japanese Leadership

Perhaps the most courageous initiative of the Abenomics program was when Japan joined the U.S.-led Trans-Pacific Partnership talks under the Obama administration. It was thus a great disappointment for Prime Minister Abe—who had to use a lot of political persuasion to drag his country into the TPP talks—when President Donald Trump withdrew the U.S. from the TPP.

However, in a demonstration of remarkable leadership, Japan picked up the reigns of the floundering TPP to lead a rapid renegotiation—now known as the Comprehensive and Progressive Agreement for Trans-Pacific Partnership—which came into force on December 30, 2018.

Even without the U.S., the new agreement is a very important initiative.

It creates an economic bloc covering 500 million people and $11 trillion in gross domestic product (around 14 percent of the world’s total GDP). With 11 signatories following the withdrawal of the U.S.—Australia, Brunei, Canada, Chile, Japan, Malaysia, Mexico, Peru, New Zealand, Singapore and Vietnam—it is also popularly known as the “TPP-11.”

The TPP-11 goes beyond mere trade liberalization and seeks to establish a more seamless environment for trade and investment. It deals with issues like services, electronic commerce, telecommunications, competition policy, state-owned enterprises, intellectual property, government procurement, transparency, anti-corruption, labor rights and the environment.

Japan’s activism in trade and investment liberalization provides a critical counter-narrative to rising protectionism in some of the world’s key markets.

Japan’s Reach Beyond the TPP-11

Prime Minister Abe has further ambitions for the TPP-11. At the first Trans-Pacific Partnership Commission meeting held in Tokyo, he said “Our doors are open to all countries and regions that agree with our principles and are ready to accept the high standards of the TPP. I hope many countries that seek free and fair trade will participate in this agreement.” And his great hope is that the U.S. will return to the fold. The Japanese government has also welcomed the UK government’s expression of interest in joining the TPP-11 once it has left the EU.

The TPP-11 is not the only deal demonstrating Japan’s new leadership for open trade and investment. Following talks that began in 2013, the EU-Japan Economic Partnership Agreement (EPA) entered into force on February 1, 2019. This deal is also very important. It creates an economic zone of 635 million people representing 30 percent of world GDP and 40 percent of world trade.

It is a wide-ranging agreement that includes commitments not only on trade in goods but also services and the promotion of bilateral investment. The major benefit for Japan of the EU-Japan EPA is that it will increase access to the European market for its domestic car manufacturers. European exporters will benefit from dramatically reduced Japanese agricultural import tariffs, with Brussels estimating savings for EU firms of 1 billion euros a year in duties.

Opening Its Procurement Processes

Overall, the EU-Japan EPA will ultimately remove 97 percent of the tariffs that Japan applies to European goods and 99 percent of those applied by the EU.

Japan will also open up its public procurement market to European firms, as well as liberalize postal services and maritime transport. The agreement is also unique in that it is the first trade deal to include a specific commitment to the Paris Agreement on climate change.

Looking ahead to the UK’s withdrawal from the EU, the Japanese government already indicated that the EU-Japan EPA could provide a very good and sound basis for future trade between Japan and the UK.

An ASEAN Free-Trade Area?

Japan is also a leading participant in the talks toward a Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership (RCEP), which seeks to create one free trade agreement between the 10 Association of Southeast Asian Nations (Brunei Darussalam, Cambodia, Indonesia, Laos PDR, Malaysia, Myanmar, the Philippines, Singapore, Thailand and Vietnam) and those six countries that already have FTAs with ASEAN—Australia, China, India, Japan, Korea and New Zealand—the “Plus-6 countries.”

The RCEP talks were launched in November 2012, but are taking much longer than expected to realize. It is, indeed, a very ambitious enterprise, as it represents half the world’s population, 30 percent of global GDP and about a quarter of world exports and foreign investment.

More recently, Japan’s trade and investment diplomacy has entered choppy waters.

In light of the U.S.’s yawning trade deficit with Japan—$68 billion in 2018, the U.S.’s fourth largest trade deficit after China, Mexico and Germany—the Trump administration has pressured the Japanese government into talks for a bilateral FTA. Another factor in this push is that American farmers are now losing out in the Japanese market to exporters from the EU and TPP-11 countries.

Although the bilateral trade talks between Japan and the U.S. have only just begun, they will likely result in further opening the Japanese market to U.S. business. While Japan is not keen on these trade talks, they could actually be beneficial. Increased international competition in Japanese markets is a sure way to improve Japanese productivity.

All things considered, Japan’s activism in trade and investment liberalization has immense geopolitical importance and provides a critical counter-narrative to the rising protectionism in some of the world’s key markets.