Study: U.S. at Risk of Increased Inequality, Mortality from Climate Change

A grave stone rests on the beach where a cemetery once stood but has been washed away due to erosion in Tangier, Virginia, where climate change and rising sea levels threaten the inhabitants of the slowly sinking island. If nothing is done to stop the erosion, it may disappear completely in the next 40 years.

Photo: Jim Watson/AFP/Getty Images

Climate change, if left unmitigated, stands to hit the U.S. with a vicious prejudice, increasing inequality and mortality rates in some of the nation’s poorest areas, according to a recent study.

The study, performed by a group of economists and climate scientists, is a first look at the potential effects of climate change at the individual county level.

The study’s authors note that populations will “adapt to climate change in numerous ways,” such as increasing the use of air conditioning, which will “likely limit the impact of climatic exposure,” while other actions, such as social conflict, will serve to exacerbate it. “Because the empirical results that we use describe how populations have actually responded to climatic conditions in the past, our damage estimates capture numerous forms of adaptation to the extent that populations have previously employed them,” the study says.

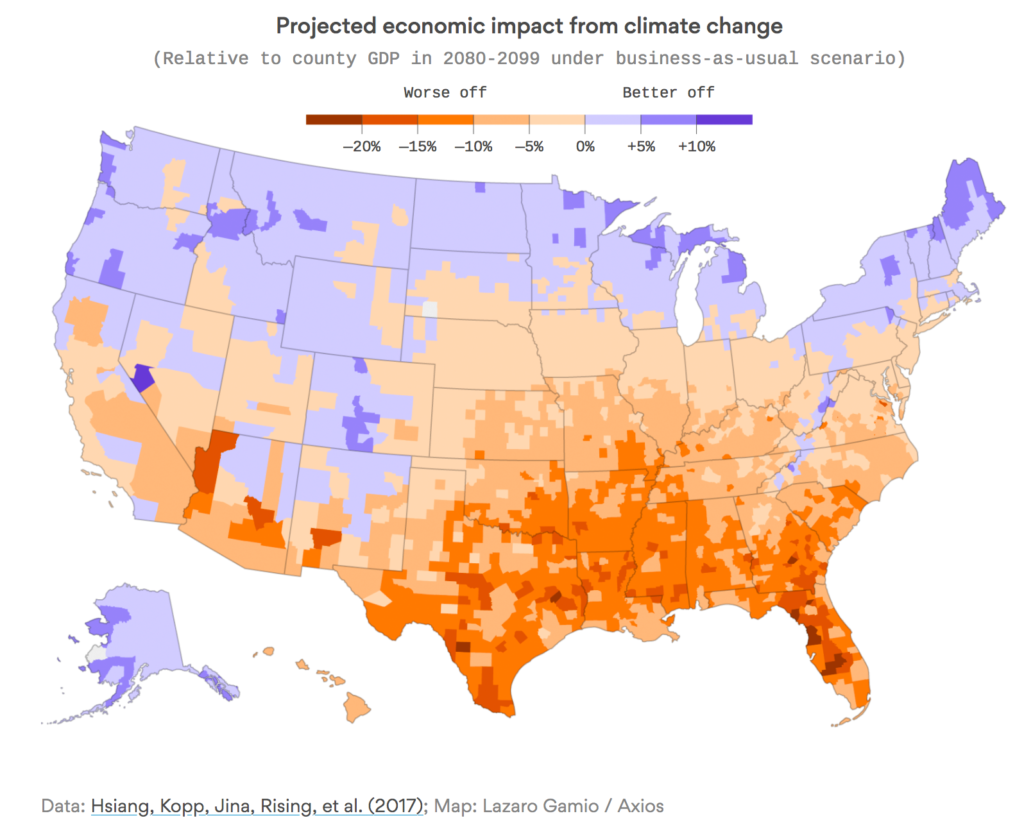

Counties identified as those likely to take the brunt of unmitigated climate change are located in the South and lower Midwest—which also happen to be some of the fastest growing areas in the U.S. These areas tend to be poorer and hotter already and could lose more than 20 percent of their income while seeing a spike in mortality rates, the study says.

The combined effects of climate change across sectors results in a “net transfer” of wealth. Where the Southern and lower Midwest states are seen losing money, those in the Pacific Northwest, the Great Lakes and New England could see income gains in excess of 10 percent, the study says. “Because losses are largest in regions that are already poorer on average, climate change tends to increase preexisting inequality in the United States. Nationally averaged effects, used in previous assessments, do not capture this subnational restructuring of the U.S. economy,” the study says.

In terms of mortality rates, there’s a trade-off as well. While the poorer, warmer states could see deaths increase, the cooler climes will see lower mortality rates. The study predicts an increase of 5.4 deaths per 100,000 people nationally for every degree Celsius rise in temperature.

“We show there are going to be as many additional deaths from climate change as there are car crashes, and possibly more,” James Rising, one of the study’s authors, told Axios. “Of the sectors we looked at, the greatest costs by far to society are going to come from those additional deaths,” Rising said.

For all its uniqueness, the study only looks at a limited number of sectors: agricultural yields, mortality, energy, labor, crime and coastal damage. For example, the study doesn’t factor in the effects of migration or technological adaptations that might be used to help mitigate the impact of climate change.

Sector Impacts

Crop yields decline as temperatures rise; however, “higher CO2 concentrations offset much of the loss for the coolest climate[s],” the study says. However, “warming still dominates,” according to the study, and the U.S. could see a 9 percent drop in crop yields for every degree of temperature rise.

Energy demands are projected to rise about 5.3 percent for every degree of warming, “because rising demand from hot days more than offsets falling demand on cool days,” the study says.

Productivity of low-risk workers—those not exposed to outdoor temperatures—is projected to drop .11 percent for every degree of warming. There’s a projected .53 percent increase in lost hours for high-risk workers—such as those in construction, mining, agriculture and manufacturing—due to warming temperatures.

Property crimes increases as a direct correlation with fewer cold days, which tends to suppress property crime rates, the study says. However, violent crime increases .88 percent nationally per degree of warming.

Potential coastal damage is “distributed highly unequally,” the study says, with the biggest hits coming to eastern coastal regions with low-lying cities. Direct economic damage is said to be in store particularly for South Carolina, Louisiana and Florida, resulting in .6 to 1.3 percent loss in gross domestic product, which could range as high as 2.3 percent in some cases.