The India-Japan Nuclear Deal: Driving Closer Relations with the U.S.?

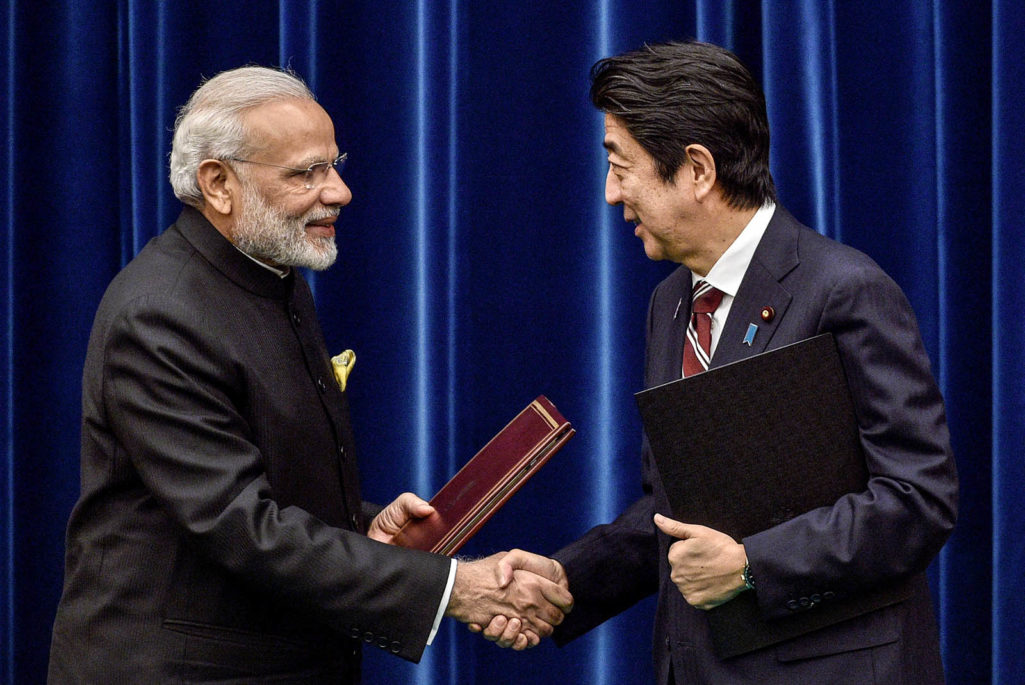

India's Prime Minister Narendra Modi (L) and his Japanese counterpart Shinzo Abe shake hands after signing a joint statement at Abe's official residence in Tokyo on November 11, 2016.

Photo: Franck Robichon/AFP/Getty Images

The recently concluded civil nuclear power agreement signed by Japan and India will cause China additional concern and further open a growing Indian market to U.S. companies.

The agreement is vital to India and its successful conclusion will enable U.S. and French nuclear organizations, which use Japanese technology in their systems and, consequently, have their own agreements with Japan, to now conduct business with India. Westinghouse and Areva, for instance, will now be free to build their nuclear reactors in India.

The agreement endured over six years of negotiation. The India-Japan talks began in June 2010 but ran into policy differences almost immediately. Japan, the only country to have suffered a nuclear attack, was adamant that any nuclear technology transfers would be predicated on the receiving country being a signatory to the Nuclear Non-proliferation Treaty (NPT), which was designed to ensure India did not have access to technology that could enable it to further its nuclear agenda. India, for its part, refused and refuses to sign the NPT, as it sees that instrument as an assault on its sovereignty. There is some justification to this perception.

When the NPT came into force in 1970 it was provisioned as a 25-year agreement. At the end of that time a scheduled conference would consider renewing and amending it to reflect the geopolitical realities of the day. In the run-up to the 1995 NPT Review and Extension conference, India faced growing pressure to sign the NPT. Prior to the 1995 NPT conference, India believed the emerging Comprehensive Test Ban Treaty (CTBT) would prevent the emergence of new nuclear-weapons states and, simultaneously, limit the qualitative and quantitative developments in the arsenals of existing nuclear-weapons states. These hopes were dashed after witnessing the proceedings of the conference. China then issued a “National Statement on Security Assurances” with India. According to this statement, which echoed its 1982 assurances, China would not use or threaten to use nuclear weapons against non-nuclear-weapons states. Indian analysts, however, noted the changed phrasing of the Chinese statement. Whereas the 1982 declaration used the term “unconditionally,” the 1995 version stated, “at any time or under any circumstances.” This change, the analysts suggested, could imply being applicable only to those non-nuclear states which signed up to the NPT. They also suggested that China’s accession to the NPT implied that it now wished to uphold that regime, thus denying India the opportunity to enhance its status in the world order.

India has refused and refuses to sign the NPT, as it sees that instrument as an assault on its sovereignty.

The UN Security Council passed Resolution 984 six days before the NPT Extension Conference began in 1995. This resolution provided security guarantees to those non-nuclear weapons states which acceded to the NPT. By implication, however, the nations that did not could not expect any guarantees, thus diminishing their security against nuclear threat or attacks, which Indian critics of the resolution pointed out. They also noted in their criticism that all Resolution 984 required was for the Security Council to meet; any proposed action could then be vetoed by any one of the Permanent Five members, including China.

These were the same questions raised in the 1960s and 1970s: Can a nation prudently base its security on the willingness and verbal bonds of non-allied nations to intervene in any aggression against it? And what if the aggressor was a nation that had provided those verbal assurances? India refused, therefore, to accede to the NPT and reiterated its reasons for doing so: by creating two classes of nations, the NPT was discriminatory and did not encourage states to nuclear disarmament. To compound the matter, New Delhi pointed out, extending the treaty only signified accepting the prevailing unequal order. The NPT, they said, required the nuclear disarmament of specified non-nuclear states while legitimizing the nuclear weapons status of the Permanent Five members of the Security Council. India, therefore refused to sign the NPT.

It is all the more telling, therefore, that Japan has now concluded the agreement to transfer civil nuclear technology to India, the first time it has done so with a non-NPT signatory. However, Japan’s Prime Minster Shinzō Abe did not make this major concession purely on altruistic grounds. He is fully aware that, in light of China’s growing economic prominence and a willingness to flex its military muscle, he needs to take measures to ensure Japan’s security. This course of action can only be hastened by the ambiguity of future U.S.-Asian policy under its incoming administration. Should the U.S. choose to withdraw from East Asia, Japan will need to, first, arm itself against an emboldened China and, second, form an alliance of sorts with like-minded democracies. This would make India the ideal candidate, especially given its cynicism vis-à-vis China’s purported peaceful rise.

Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi, for his part, needs access to nuclear technology to fuel India’s economic growth while, simultaneously, catering to India’s international obligations regarding climate change. The current smog in New Delhi will undoubtedly emphasize the move towards cleaner fuel sources. Like Abe, Modi is aware of the Chinese threat that India faces and will wish to form alliances with Asian democracies since India will remain unable to counter China single-handedly in the near term.

Increased Opportunities for Business

Access to Japanese nuclear technology will also free up U.S., French and Japanese companies to build their nuclear reactors in India, relieving India of its dependence on Russian technology. It is this imperative that draws India and Japan closer.

However, there is more to Modi’s trip to Japan than just nuclear technology. Japan wants India to purchase its high-speed train technology and is investing in a Mumbai-New Delhi economic corridor. Over 1,200 Japanese firms operate in India and wish to ramp up their business. They seek a better business environment: simplified land acquisition laws, simplified taxation laws and better standards and certification systems. Modi’s Goods and Services Tax promises to deliver on many of those demands.

This situation brings with it many business opportunities. India is slowly but surely being drawn into the U.S. camp, directly and through its ties with countries such as Japan and Australia. There is little contrary evidence to suggest that the U.S. and India will not continue to develop their relationship under President-elect Donald Trump’s administration.

In addition to accessing the advanced military systems of the U.S., owing to recently being recognized as a “major defense partner,” India will want to access the business opportunities available there in order to deepen their strategic ties. Under a Trump administration, this will likely turn out to be a quid pro quo arrangement, giving U.S. technology firms and its financial sector, in addition to its nuclear technology providers, access to the growing Indian market.