Capital Markets of the Muslim World: The Paradox Within

This view shows the Kuala Lumpur city skyline. Within the Muslim world, Malaysia has come to dominate the Islamic finance/capital markets space by successfully replicating the key components of a well-developed financial sector in a Shariah-compliant way.

Photo: Mohd Rasfan/AFP/Getty Images

A list of the top 30 sovereign wealth funds (SWFs) shows at least half originating from Muslim countries. Of all the world’s SWFs, 41 percent are from the Organisation of Islamic Cooperation (OIC) countries.

As of August 2016, SWFs from OIC member countries accounted for about $3 trillion, or about 44 percent, of total SWF assets under management. This is substantial by any measure, but it has not translated into capital market development in these countries.

Financial Clout Alone Does Not Guarantee Strong Capital Markets

Despite this apparent financial clout, capital markets in the Muslim world remain underdeveloped. It is obvious that this SWF wealth could be deployed in more advantageous ways. For example, despite the dominance of Muslim SWFs, there isn’t a single city from the Muslim world ranked in the top 10 in the Global Financial Centres Index of the top financial centers of the world for 2016. Dubai ranks 18th and not even Istanbul or Kuala Lumpur make the top 20.

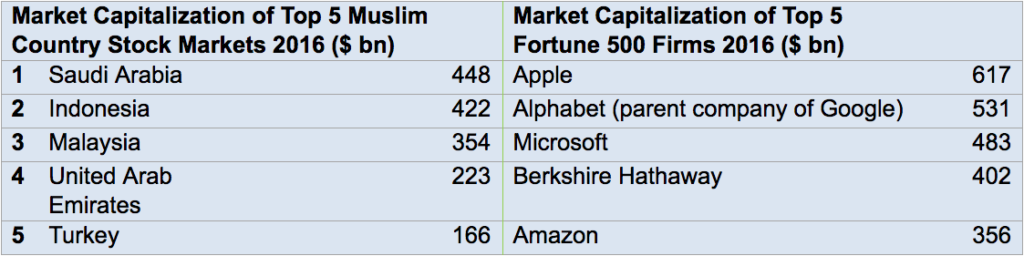

Next, if we examine the market capitalization of stock markets in the Islamic world, the underdevelopment is glaring. The table below shows the market capitalization of the five largest stock markets of the Muslim world compared to the companies with the largest market capitalization. Apple, Alphabet (parent of Google) and Microsoft all have a market cap larger than the total Saudi Arabian stock market, the largest among Muslim country stock exchanges.

Two things jump out of this table. First, stock markets of the Muslim world are tiny by global standards. Second, given that Muslim nations dominate the league of SWFs, it also points at the lack of intermediation within the Muslim world; Muslim wealth is largely not being invested within the Muslim world.

The third evidence of the absence of capital market intermediation comes from a 2013 report. Studying asset allocation by households in different regions of the world, the study found that of the estimated $4 trillion aggregate household wealth within Middle East and North Africa (MENA), 44 percent was held as cash deposits and a mere 10 percent invested in equities. Looking at the market capitalization numbers above, the minimal amount allocated to equities by MENA households may be a trend across the Muslim world.

The final piece of evidence is the increased number of companies from OIC countries that resort to ADRs/GDRs (American Depository Receipts or Global Depository Receipts). While ADRs are a means by which foreign listed companies can seek to tap equity capital from the New York Stock Exchange, GDRs are for the London or Luxembourg exchanges.

From a mere five companies in 1993, there are now about 150 companies from the Muslim world that have issued ADRs and/or GDRs—including the likes of Adaro Energy, Indofood and Bank Mandiri from Indonesia and Top Glove Kuala Lumpur Kepong and Malayan Banking from Malaysia, to name a few. Given the issuance requirements of these markets, these are probably among the most high-profile companies based in the Muslim world. However, they have had to resort to ADRs/GDRs simply because their domestic markets were too shallow for their needs.

Where Does the Problem Stem From?

These underdeveloped capital markets stem from a chicken-or-egg scenario. Unless the large SWFs invest in these markets, they will remain small; and given their current size, the SWFs cannot invest without moving the markets and incurring huge market impact costs. The lack of technology, expertise or infrastructure cannot be the case, for these can be acquired or hired. What then, is the missing ingredient? It is the “soft” issues—those relating to governance, accountability, transparency and rule of law among others. Muslim countries, including the major ones, perform poorly on these parameters, according to the World Bank Governance Indicators.

When company accounts cannot be trusted; when rule of law is not always upheld; when corruption and politics get in the way of business decisions; when the enforcement of contracts is subjective; and when rules and policies can turn on a whim, trust cannot possibly take root. And where trust and compliance to the rules are missing, capital markets cannot function optimally. The net result is disintermediation and the presence of underdeveloped markets.

By most measures of market development, capital markets of the Muslim world show serious lag. Yet, governments in Muslim countries—barring Malaysia—by and large appear to show little interest in capital market development.

This has serious consequences. Apart from continued reliance on the West for financing, which, through the intermediation of its banks, currently recycles investments from Muslim SWFs to lend to poorer Muslim nations, there are several other problems. First, stunted capital markets stifle entrepreneurship. Without small enterprises, an industrial base is difficult to build. The inability to harness savings into business investments and decent returns will result in leaks and capital outflows, and as a result, economies cannot function well. Finally, and perhaps most damaging of all, is the fact that underdeveloped capital markets mean a higher cost of capital for firms—a direct consequence of which is national competitiveness.

Setting the Tone

Within the Muslim world, Malaysia stands out as an exception. Having undertaken several innovative and pioneering steps, Malaysia has come to dominate the Islamic finance/capital markets space.

During a 15-year timeframe—from 2000-14—Malaysia accounted for about two-thirds of all issued and outstanding sukuk (or Islamic bonds). It was also the first to come up with a formal Shariah stock screening process that evaluates listed stocks for Shariah compatibility. This in turn has enabled players to participate in the first Islamic REITs (Real Estate Investment Trusts), Islamic mutual funds and exchange-traded funds.

The country’s Islamic Interbank Money Market is the only one of its kind in the world. This Islamic Interbank Money Market made it possible for the government to require all commercial banks to offer Islamic banking services. It has also removed a potential bottleneck to the growth of Islamic banking by making liquidity management just as easy and efficient as it is in conventional banking.

Today, Malaysia has successfully replicated all the key components of a well-developed financial sector in a Shariah-compliant way. Malaysia’s progress demonstrates that other Muslim countries can follow suit if their policymakers make the right decisions if they are willing to adopt a progressive interpretation of Shariah requirements and if they demonstrate willingness to experiment with entirely new processes.

Another important factor is the strong government support for Islamic banking and finance, particularly in the form of enabling regulations and tax reforms to provide for tax neutrality, which ensures that asset-based transactions in Islamic finance are not hindered by additional taxation, and by investing in trading and other market infrastructure and human capital development to support the continued growth of the industry.