The Southeast Asian Clean Energy Opportunity: Navigating the Risks

Trainees assemble a solar lantern at a workshop inside the Technical Education and Skills Development Authority (TESDA) headquarters in Manila. TESDA, a government-run school trains people to make solar-powered light bulbs using discarded plastic soda bottles.

Photo: Noel Celis/AFP/Getty Images

The quest for energy security is driving policymakers in Southeast Asia to review their energy mix, but policy, insufficient utility support and grid stability, and a lack of transparency in the permitting process could hold back much needed investment in clean energy in the region.

As regional economies have moved from being fuel exporters to importers, and given the volatile geopolitical situation elsewhere with trouble continuing to brew in the Middle East and in Russia-Ukraine, smaller countries in Southeast Asia are looking for ways to have more control over their domestic energy supply.

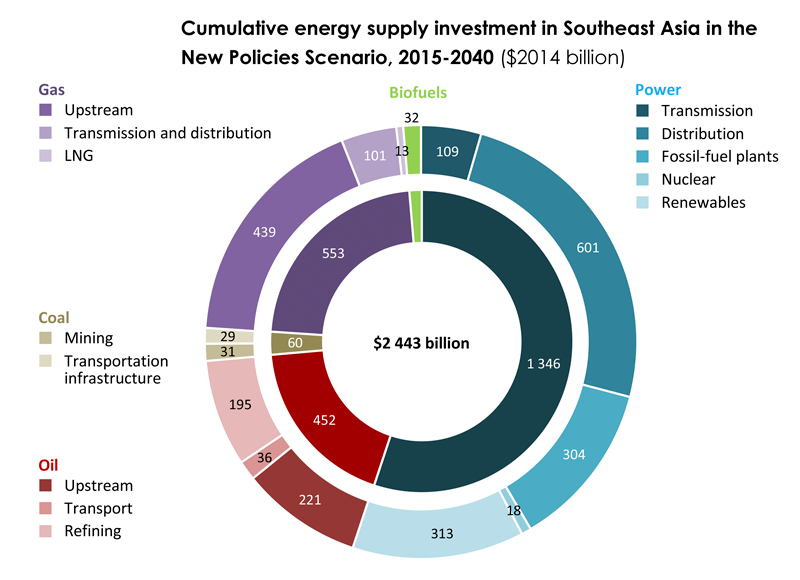

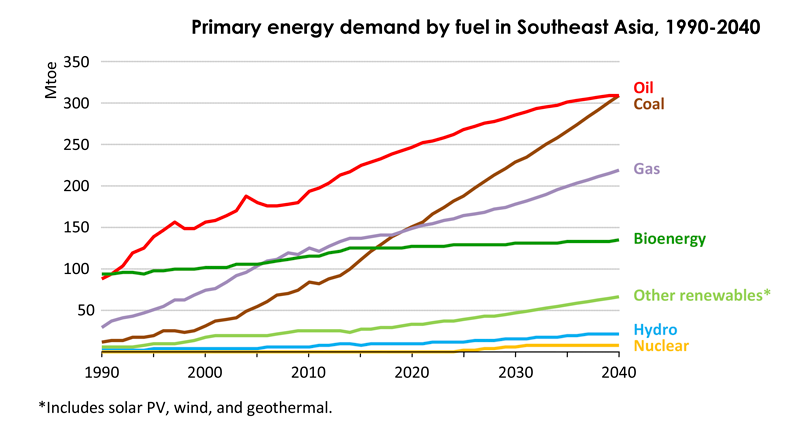

Policymakers are also cognizant of the increasing energy demand across the region as the regional economies continue to grow. Between 2015 and 2040, in the New Policies Scenario, Southeast Asia will need a cumulative $2.4 trillion in investment in energy supply.

Renewing the Energy Mix in Southeast Asia

Southeast Asia is blessed with good irradiation from the sun; certain countries have great wind resources that can be tapped and others have rich hydro resources.

Various targets have been proposed in different countries for different energy mixes. Governments are continuing to make new policies or enhance existing ones, which are acting as catalysts for investment in the region’s renewable energy space. These long-term plans are further broken down into implementation targets in the area of solar, wind and hydro, with smaller targets to be met by specific dates. As these targets are achieved, more lessons are learned and that drives further commitments.

In the region, Thailand started focusing on renewable energy in earnest about four years ago. The Philippines, Indonesia and Vietnam have followed with various projects materializing periodically. Early phase success has won the confidence of policymakers and private investors, thereby increasing activity in this space.

Electricity prices in Southeast Asia are high, or will likely be so if fossil fuel subsidies are taken away—and this has started happening. For example, Indonesia has started to pull back on subsidies. This makes renewable energy a competitive—and often compelling—proposition.

Southeast Asia also has a long history of private investment—whether domestic or foreign. As a result, there are many benchmarks in place that give comfort to the private sector. At a micro level—apart from policy at the macro level—one of the key elements in infrastructure investment of any kind is the execution and permitting process—and while greater efficiencies in this regard are still needed, things have improved.

Dealing with Risks

Though policy has improved in recent years, this area remains a key risk. Chief among those risks is the possibility of a material change of a policy, particularly reverting back to a greater reliance on fossil fuels. Another one remains the slow implementation of policies, in which case private investors lose patience and divert their attention and money to alternative geographies.

A second major challenge in Southeast Asia is the insufficient utility support and grid stability. For example, in the Philippines, a sudden swing in power generation by solar plants owing to solar overcapacity in Negros led to curtailment. The grid in many parts of Southeast Asia does not have the capacity to manage the new, intermittent sources of additional power. Investment is required in the grid for the utility companies to effectively manage these new sources.

The third risk confronting investors is around efficiency and transparency in the permitting process. Different markets have different types of policies to promote private investment, and sometimes there are question marks about how and why decisions are made, which can be disturbing for prospective investors.

In the Philippines, permitting works on a “first come, first served” basis—but how does one determine who has met the appropriate criteria? It can be very subjective and opaque. If the developers are not checked thoroughly enough and results disclosed transparently, the whole process can stalemate. This is, in fact, happening already, where the Philippine national Energy Regulatory Commission has put on hold decisions on feed-in tariff allocations owing to complaints made to the Department of Energy from developers that certain solar projects were not fairly evaluated.

Project Bankability Concerns

Southeast Asia’s energy requirements are immense, and despite the governments’ best efforts to promote private investment in renewable energy to address the energy shortfall, it is going to be hard to meet future energy demand.

Many projects are being built on a smaller scale using just equity and no debt because the banks, due to a variety of factors, are not always willing to lend to developers until infrastructure projects become operational. Additionally, in order to meet tight policy implementation deadlines, there is often not enough time to arrange full project finance from the banks, which can take up to nine months. These factors limit the availability of truly bankable projects.

As a result of these factors, despite the availability of the right ingredients in the form of an abundance of resources and a strong government push for renewable energy, annual investments in the renewable energy sector are much lower than required.

Can Governments Inspire More Confidence?

Process is always a factor in Southeast Asia. Investors have some empathy for policymakers who want to make sure they are making forward-looking decisions, but occasionally, it takes governments too long. The market is in a stop-start scenario in many countries in the region and momentum gets lost. The Thai solar sector is a good example, where new planned phases of purchase power agreement issuance have stalled several times. As the region looks to draw private investment, this is a risk as overseas investors always have the choice of where to put their money—as a result of this, some countries could lose out on potential investments.

Another issue to address is the permitting bottleneck, which can create uncertainty for investors. For instance, developers need to obtain multiple certificates and approvals for any project from multiple government agencies, and this can be prohibitively time-consuming due to its complexity and lack of interdepartmental collaboration. However, this is an evolving situation and things will change as authorities gain more experience.

Finally, all these processes and decisions need to be made more transparent. Investors worry about some idiosyncratic policies and indeed reversals in policies that can have a retroactive impact on the investment. To continue to generate and retain private sector interest in the sector, policymakers need to be more consistent, efficient and transparent.