A Relic of Cold War Past? Why Vietnam Still Matters

Motorcyclists ride past a cloth boutique selling locally made products in downtown Hanoi, Vietnam. The country has the second fastest growing economy—just behind India—in the world.

Photo: Hoang Dinh Nam/AFP/Getty Images

The long tail of America’s defeat in Vietnam is still fresh in the memories of both countries; last year marked the 40th anniversary of the Fall of Saigon. Relegated to the periphery of U.S. national security interests since the end of the Cold War, Vietnam has ceased to become an important variable in U.S. presidents’ labile foreign policy equations. Even so, Vietnam should not be dismissed, least of all by the U.S., as a marginal actor of Lilliputian stature on the geoeconomic stage.

The country holds promise not only for the U.S. defense industry, but the private sector as well. Vietnam is one of the fastest growing economies on the planet, growing at a steady 6.7 percent, ranking it No. 2 on the list of the fastest growing nations, just behind India. More than 2,000 projects worth $15.8 in foreign direct investment were given license to operate in Vietnam as of December 2015—up nearly 27 percent from 2014 in terms of number of projects—according to the country’s General Statistics Office. In total, $23 billion in FDI was registered in the country in 2015, the GSO said, up 12.5 percent over 2014.

Today, Vietnam is nation of roughly 90 million people. About the size of New Mexico, this lizard-shaped Southeastern Asian country has been under communist rule since 1975. Despite the regime’s dogma of central planning, Vietnamese authorities have in recent years shown flexibility in adapting state ownership to the modern world. Perhaps the biggest indication of Vietnam’s seriousness about economic modernization was stated in 1996 by then-Communist Party Secretary General Đỗ Mười at the Eighth National Party Congress: “Our present slogan must be capital, capital and more capital.”

In another sign of its readiness for market economy, Vietnam joined the World Trade Organization in 2007.

Since the introduction of Đổi Mới (to reform) in 1986, the government moved to abandon price controls, liberalize domestic banking regulations and encourage foreign investments. In another sign of its readiness for market economy, Vietnam joined the World Trade Organization in 2007. Traditionally an agricultural economy, Vietnam is now primarily a service-based and industry-based economy, accounting for 42 percent of total GDP.

According to World Bank statistics, Vietnam’s economy is 57th in the world, and the second largest in the communist world; however, its human rights record remained dismal by all credible metrics. If the U.S. is serious about confronting human rights abuse around the world, Vietnam has to be a necessary part of American global strategic mission. One way to pressure Vietnam to guarantee and protect the civil liberties of its citizens is China.

China Key to Political Reforms in Vietnam

In the early years of the Cold War, western democracies came to accept communism as a monolithic bloc without breaks or fissures. We now know that was not true. The fallout between the Soviet Union and the People’s Republic of China (PRC) in 1960—which President Richard Nixon exploited with his high-profile visit to the latter in 1972—and the subsequent collapse of the former in 1991 removed the mirage that communism was an impervious system.

Just as the Sino-Soviet split revealed the cracks in communism, the supposed ideological symbiosis between Vietnam and China, supported by their cultural commonality and civilizational ties, is illusory given the enmity that has historically existed between them. Relations between the two reached new heights in recent years because of territorial disputes in the oil-rich South China Sea.

Since 2014, Pacific countries feeling imperiled by an increasingly aggressive and bellicose China have been seeking to deepen economic, military and strategic ties with Washington. Vietnam in particular sought bilateral security cooperation with other powers in the region, in light of Beijing’s maritime claim to the South China Sea’s Paracel and Spratly Islands, over which Hà Nội also asserted sovereignty. Signaling yet another step to leave Beijing’s orbit of influence, Hà Nội announced in 2014 that it had secured the cooperation of India, the world’s largest democracy and Asia’s third-largest economy, for a 15-year loan of $100 million in defense deals.

For the U.S., this presents an opportunity to vigorously push for reforms in Vietnam. The Obama administration had already announced a policy of “rebalancing” Asia by promising to redeploy almost two-thirds of U.S. air and sea power to the region by 2020. If Washington can convince Vietnam of the credibility of American commitment to Asian-Pacific regional security amid China threats, then there is a real chance for democratic changes in Vietnam.

Demographically, Vietnam is changing: 41 percent of the population are under the age of 25 and at least half were born after 1975. For these younger generations, the Vietnam War is a distant and non-relatable past. Less ideological than their forebears, they are a malleable and practical people. They still accept communism, but not wholeheartedly. Many who joined the communist party did so not out of national pride, but as a means for getting ahead. For them, finding the right institutional and policy formulas to achieve sustained economic growth is more important than defending a Maoist-Stalinist system of control that might seem quaint and outdated to the generations that grew up with social media.

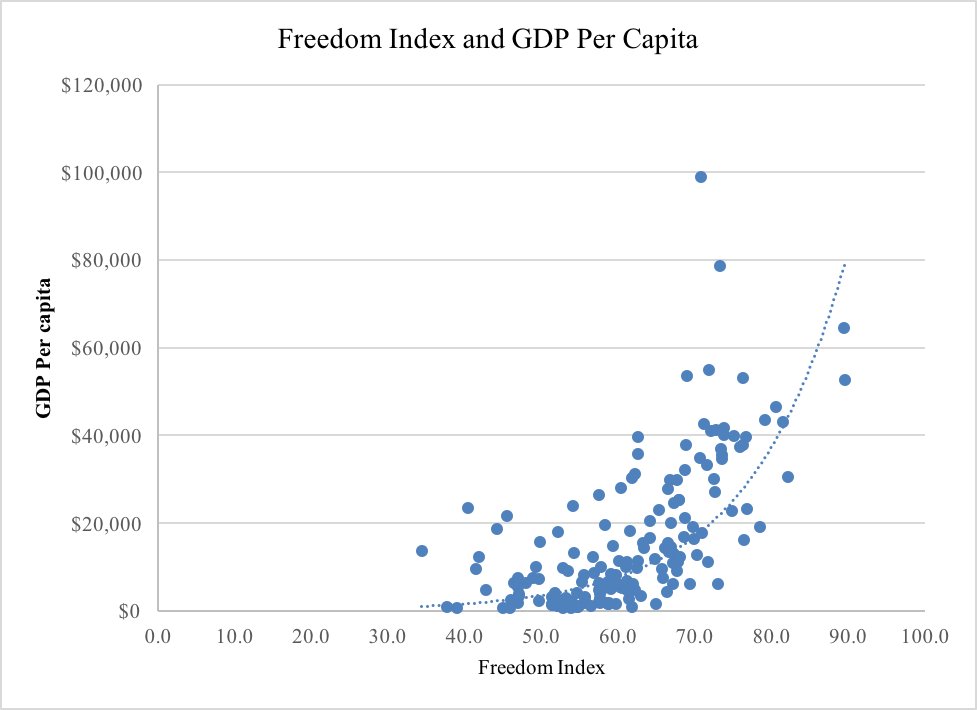

One of the challenges for the U.S., therefore, is to convince the youth of Vietnam—their country’s future leaders—to democratize. The chart below presents the relationship between freedom, indexed on a scale of 1 (least free) to 100 (most free), and GDP per capita for more than 150 countries in the world.

In the final analysis, a hegemonic China more bent on flexing military muscle in Asia-Pacific and a Vietnam undergoing changing age demographics offer the most significant opportunity for Washington to recalibrate U.S.-Vietnam relations to date since the end of U.S. trade embargo on Vietnam in 1995. In the past, Hà Nội had resisted and spurned overtures from Washington to embrace democratic openness. That was what the Clinton administration had tried to do in the 1990s. As relations between Beijing and Hà Nội continue to deteriorate, Hà Nội must be willing, this time around, to heed Washington’s open calls for democratic reform in return for American security in the region.

This is why President Obama’s recent trip to Vietnam, the first high-profile U.S. visit in almost a decade, was both timely and necessary. Though the trip did highlight a concrete U.S. “rebalancing” policy in the Asia-Pacific, such as the lifting of decades-long U.S. ban on lethal arms sales to Vietnam, in the wake of China’s none-too-subtle expansionist ambitions in the region, the symbolism the trip evoked was more powerful, underscoring the ongoing yet slow and painful process of collective therapy through which America sought to forget bad memories of the Vietnam War defeat by way of seeking to normalize relations with its former adversary.

If, as former Secretary of State Henry Kissinger reminded us in his 1996 book “Diplomacy,” roads are made for walking and “America’s ideals will have to be sought in the patient accumulation of partial successes” in an imperfect world, then President Obama’s Vietnam visit last May represents another step on the road toward reconciliation and national healing. In that sense, Vietnam still matters.

Another version of this article was published in the Examiner.