Antibiotic Resistance is Next Great Global Challenge

A researcher works at the microbiology lab of the Universitair Ziekenhuis Antwerpen, a hospital in Antwerp on August 13, 2010. Media reported at the time that a man of Pakistani origin died in Belgium in June following an infection of a new super bacteria, NDM-1, that is resistant against almost every antibiotic.

Photo: Jorge Dirkx/AFP/Getty Images

Bacteria have now evolved to deflect our most powerful antibiotics—and we only have ourselves to blame. Antibiotics are overused in farming and medicine. If we want long-term solutions, we need to look beyond the search for new antibiotics. Today, world leaders turn their attention to this global threat, and they must use this opportunity to implement a strong international plan to protect an essential global commons.

Since Alexander Fleming’s discovery of penicillin in 1928, antibiotics and other types of antimicrobials have protected hundreds of millions of people from infectious diseases and are now taken for granted as part of modern life. But there are trillions of beneficial bacteria that are essential for our bodies and Earth’s living resources. Unfortunately, overuse is increasingly depleting this global common resource and replacing it with increasingly hard-to-treat resistant microbes. A recent study estimates 200,000 babies die each year as a result of this overuse.

The problem is that the typical solution is to invest in innovation to find new antibiotics. In a recent commentary in the journal Nature, I argue, with colleagues, that this approach tends to downplay important solutions such as hygiene, sanitation, vaccines or even cultural changes. In fact, the same study estimating the toll of resistance in newborns also estimated that a pneumococcal vaccine could prevent 11.4 million days of antibiotics treatment for pneumonia, likely reducing the burden of resistance significantly. It is time to reframe the debate and recognize that the true exhaustible natural resource—on par with the ozone layer and our stable climate—is the global community of microorganisms, not the antibiotics.

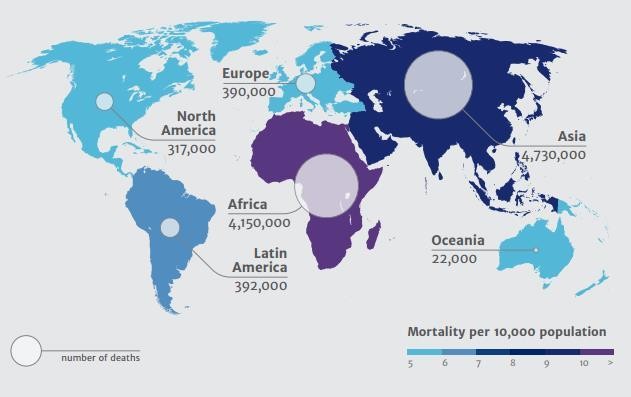

Much like fossil fuels, antimicrobials have become crucial building blocks of modern civilization, and we do not have a perfect substitute ready. With global transport and increasing rates of international spread, antimicrobial resistance is increasingly becoming a global problem in need of coordinated systemic action. The repeated calls over the past years for an organization similar to the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) for antimicrobial resistance are therefore very pertinent.

On Sept. 21, in conjunction with the UN general assembly in New York City, heads-of-state met to take action at the UN high-level meeting on antimicrobial resistance. Short of a UN convention for antimicrobial resistance, leaders at the UN should set global targets to curb overuse of antimicrobial drugs, limit levels of resistance and accelerate implementation of the World Health Organization’s global action plan from 2014. Such targets must secure stronger accountability, but must also emphasize the many benefits of microbes.

Changing Perceptions

Microorganisms are a global public good. They made Earth livable before humans evolved and they continue to do so. They do this not only by being the engines that run the critical nutrient cycles and secure air, water and soil qualities, but also by helping our bodies’ digestive and immune systems develop. Without microbes, there would be no humans.

Human perception of microorganisms does not reflect this, nor does our basic knowledge about them. A 2015 WHO survey across 12 countries found that 64 percent of the public wrongly believes that antibiotics also work for viral infections such as influenza and colds. Such basic knowledge gaps lead patients and physicians to reach for antibiotics without appreciating the costs of antimicrobial resistance.

If leaders at the UN want to curb the long-term challenge of resistance, they must take a diverse and affirmative set of actions. Underlying them all, they must connect the awareness of human civilization to the global microbiome. This involves putting microorganisms on the global school curriculum alongside climate change and other global environmental challenges.

That said, passive learning has rarely been a successful strategy for creating societal change. Luckily, the decreasing costs of gene-sequencing technology now allows society at large to participate in monitoring the microorganisms (benign and resistant ones) in their own bodies and in the environment. The rapid increase in citizen and public science as a tool for both monitoring the environment and changing societal norms must now spread faster than antimicrobial resistance.

Curbing Use

Non-essential antimicrobial use must be scaled back both in livestock production and in humans. Without action, global antimicrobial consumption in agriculture may increase 50 percent and double in emerging economies such as India, China and South Africa. As illustrated by the recent international spread of resistance to the last-resort drug Colistin on a mobile gene that can easily be transferred between different bacteria, such a scenario would have far-reaching consequences for human health.

One of the most important issues is to globally phase out the use of antibiotics as growth promoters in farming and ensure that farmers and vets do not unscrupulously relabel this as a preventive treatment. A global economic plan to subsidize the transition to antimicrobial-free production forms is necessary.

For humans, it’s the highest priority to curb unrestricted over-the-counter sales as well as black market sales. In low- and middle-income countries, financing of improved sanitation, hygiene and vaccine access is of utmost importance to reduce the reliance on antimicrobials as replacement for these necessary development steps.

This piece was first published on the World Economic Forum Agenda blog.