ASEAN Integration: A Work in Progress

Indonesian workers raise an Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) flag surrounding the ASEAN conference venue in Nusa Dua, Bali.

Photo: Sonny Tumbelaka/AFP/Getty Images

The prospect of more protectionism in the West—and the Association of Southeast Asian Nations’ (ASEAN) substantial reliance on the U.S. and Europe for driving export growth—has highlighted the vulnerability of the region’s growth model and strengthens the case for promoting intra-regional trade.

Against this backdrop, the ASEAN Economic Community (AEC) has an important role to play. Its objective is to establish a common market that extends the principles of free trade to the movement of mobile factors of production, such as labor and capital.

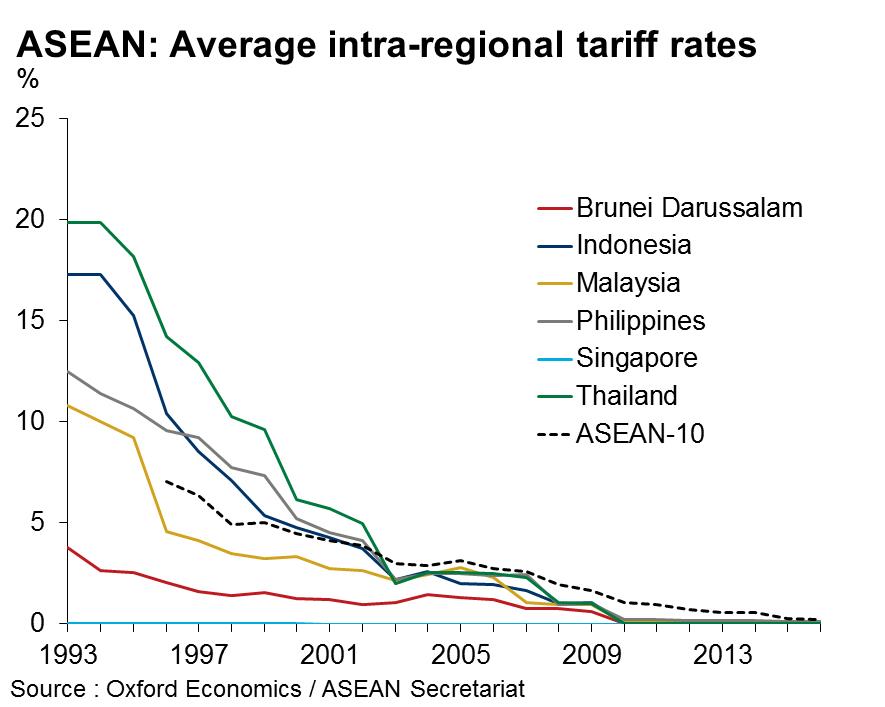

Progress has been made in the right direction. Tariffs within the ASEAN region averaged close to 0% by the time the ASEAN Economic Community was formally launched at the end of 2015.

While the AEC is slowly progressing toward that goal, and progress has been made with members signing key agreements on investment and labor mobility, trade deals, and the removal of most tariff lines, various challenges remain.

Bright Spots

The realization of a fully functional AEC would allow businesses to plan pan-ASEAN investment strategies and treat the economic block as a single production hub rather than fragmented domestic hubs. Toward this goal, the AEC has laid several foundations:

- Member nations of the ASEAN have signed agreements such as the ASEAN Trade in Goods Agreement, ASEAN Multilateral Agreement on the Full Liberalisation of Air Freight Services, ASEAN Comprehensive Investment Agreement and the ASEAN Agreement on the Movement of Natural Persons.

- The ASEAN grouping has also signed free trade agreements with six key trading partners, namely China, Korea, Japan, Australia, New Zealand, and India. These economies account for roughly 42 percent of extra-ASEAN trade.

- To harmonize these existing agreements, the block is also leading the negotiations of the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership (RCEP). As chair of RCEP negotiations, ASEAN has taken the role of facilitating discussions, as well as determining what content is discussed, in their efforts to strive for ASEAN centrality, the principle that sees ASEAN as a primary authority within the regional architecture. The RCEP has assumed greater significance in the regional architecture, given the likely demise of the Trans-Pacific Partnership.

- According to the latest ASEAN scorecard, published by the ASEAN secretariat at the end of 2015, at least 99 percent of intra-regional tariff lines for the ASEAN-6 (Brunei, Indonesia, Malaysia, Singapore, Thailand and the Philippines) and 91 percent for the CLMV countries (Cambodia, Laos, Myanmar and Vietnam) have been removed. Average tariff rates have gone down from a regional average of 11 percent in 1993 to 0 percent for most countries.

- To make these initiatives even more effective, the ASEAN Tariff finder was launched in August 2016 to help small businesses take advantage of the different preferential tariffs they are entitled to under the ASEAN Trade in Goods Agreement (ATIGA) and other FTAs.

- In terms of labor, so far, members have signed eight mutual recognition arrangements (MRAs). These are frameworks to support mobility of skilled professionals, mainly through information exchange and standardization of practices.

- The ASEAN Single Window (ASW) customs system was formally launched in 2013. It is a web-based system to expedite customs clearance. To connect to the ASW, countries such as Brunei, Indonesia, Malaysia, the Philippines, Thailand, and Vietnam have begun work to establish their own national windows. Myanmar, Laos and Cambodia prepared customs platforms before setting up their own windows. Notably, while this is promising, the ASW is still underutilized, with the interface not being used for their import and export transactions and companies still facing difficulties at the border as document requirements impede trade flow.

The improvements listed above have freed up the movement of goods, especially as tariffs have been removed within the region, but they still exist vis-a-vis the rest of the world. Some noticeable progress has already been made. Many ASEAN countries have seen trade with fellow members outpace their trade with the rest of the world between 2007 and 2015, with the notable exception of the Philippines, Vietnam and Myanmar. While Vietnam and Myanmar saw their exports to China drive overall export growth in this period, the Philippines experienced generally disappointing export growth. Brunei, meanwhile, remains an outlier as it depends on oil exports.

Obstacles to Deeper Integration

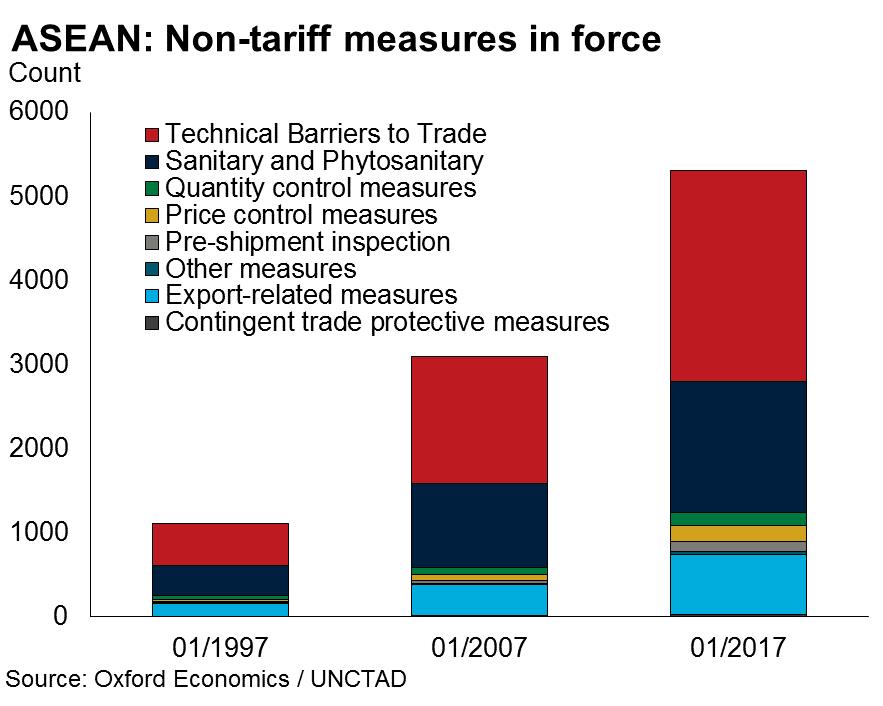

The overall improvements in trade have been modest, and it warrants a look at what stands in the way of further expanding intra-regional trade. The proliferation of non-tariff protectionist measures, a lack of enforcement mechanisms, and the pressure to prioritize domestic over regional interests still weigh heavily on the progress of the AEC.

More specifically, while tariffs have been removed, they have been replaced, to some extent, by non-tariff measures (NTMs). Technical barriers to trade and sanitary and phytosanitary measures (such as hygienic requirements, treatments to eliminate plant and animal pests) make up most NTMs, ensuring that certain standards are met, and ensuring safety and conformity of products. However, members have increased the number of other NTMs, which are not exactly in the spirit of a common market. Measures like quantity and price controls have increased, further restricting trade movement. In addition to the proliferation of NTMs on imports, origin markets are also further hampering the freer flow of trade by implementing restrictions on their own exports, such as quotas, re-export rules, registration requirements and outright prohibition.

Although tariff lines have been reduced, the proliferation of NTMs still impede the free flow of goods.

In terms of the free movement of labor, while several AEC members have large immigrant populations, this predates the establishment of the AEC and its growth has slowed down. In fact, the three countries in the ASEAN-6 with the largest immigrant population and share of immigrants—Singapore, Malaysia and Thailand—have seen slower growth rates.

In general, progress has been slow so far because there is a dearth of collective political will within ASEAN to make concessions, as well as to introduce necessary reforms at a national level. To illustrate further, the financial services and banking sector is one sector where little progress is likely to be achieved without some willingness to make concessions. The standoff between Indonesia and Singapore over reciprocal market access in recent times is a case in point.

Moreover, compliance to regulations within the grouping is particularly difficult in the absence of sanction mechanisms and a governing body to enforce commitments and rules. Only peer pressure has incentivized member states to respect commitments, giving them little incentive to implement reforms that go beyond securing or enhancing their national interests.

This contrasts with the EU, which has the European Commission to monitor behavior, enforce rules, and impose fines on members. Thus, domestic interests often tend to outweigh the push for regional integration within the AEC.

AEC’s Increased Relevance

ASEAN member states have stepped up and pushed on with key initiatives that bring the region closer to becoming a more unified economic market, which is imperative given rising Western protectionism. Ironically, the current global economic environment may actually contribute to these AEC initiatives picking up pace.