Asia Struggles To Provide Inclusive Development

Malaysian families enjoy dinner overlooking Kuala Lumpur. Malaysia leads the pack among emerging Asian economies when it comes to inclusive development, according to the World Economic Forum’s Inclusive Development Index 2018.

Photo: Manan Vatsyayana/AFP/Getty Images

Malaysia leads the pack among emerging Asian economies when it comes to inclusive development, according to the World Economic Forum’s Inclusive Development Index (IDI) 2018, while India is the worst Asian performer, ranked 62 out of 74 emerging economies globally.

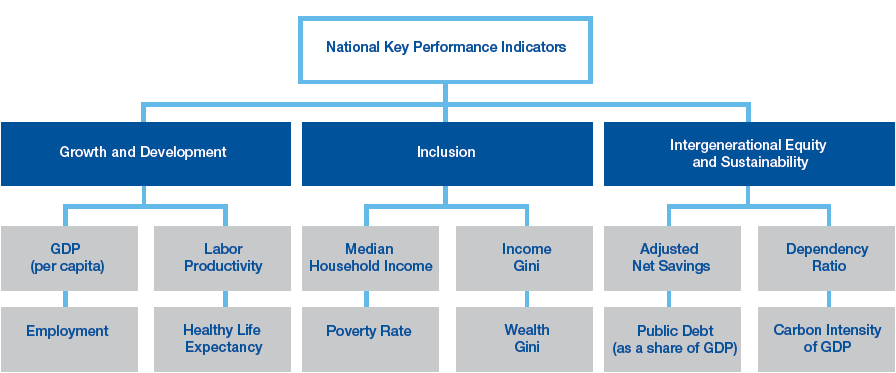

The IDI is a new metric of national economic performance that measures how 103 economies fare along 11 dimensions of economic progress in addition to economic growth alone. It is based on three pillars—growth and development; inclusion; and intergenerational equity and sustainability.

Exhibit: Inclusive Growth and Development: Key Performance Indicators

According to the World Economic Forum, the IDI shows that economies are still focused on policies that prioritize short-term economic growth over policies that contribute to inclusion and sustainability, despite concerns about social inequality. It says specifically that “prioritizing economic growth over social equity for decades has led to historically high levels of wealth and income inequality and caused governments to miss out on a virtuous circle in which growth is strengthened by being shared more widely and generated without unduly straining the environment or burdening future generations.”

For example, in the past five years, social inclusion has declined or remained unchanged in 20 of 29 advanced economies, while intergenerational equity has deteriorated in 56 of 74 emerging economies. The excessive focus on gross domestic product as the primary measure of economic performance has led to a neglect of other aspects that contribute to economic well-being, such as economic security, employment opportunity and quality of life, among others.

The Lack of Inclusive Development in Emerging Asia

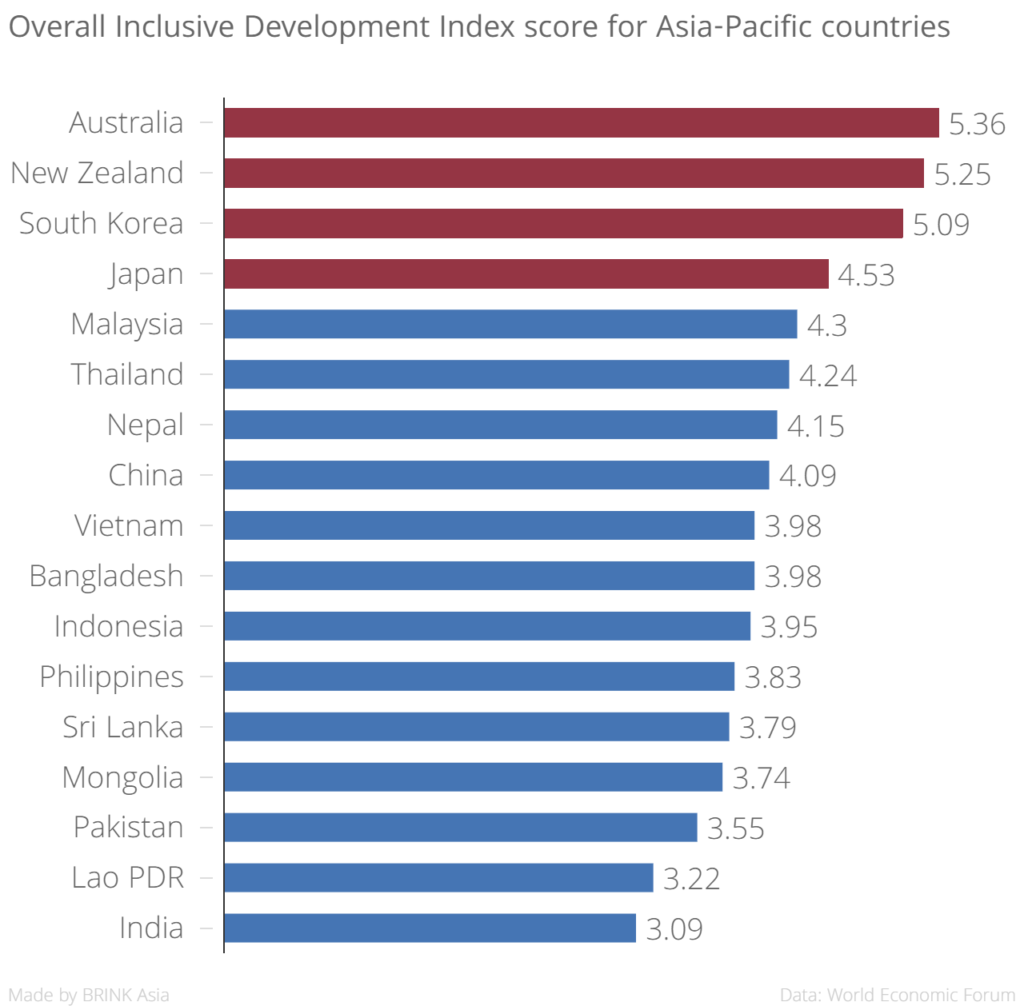

Emerging Asian economies generally fare worse than counterpart economies in Latin and South America and in Central and Eastern Europe. Among emerging economies globally, Malaysia and Thailand fare better than their Asian counterparts and are ranked 13th and 17th, respectively, with scores of 4.3 and 4.24 on a scale of 7.

Note: IDI scores are based on a 1-7 scale. Advanced economy (in red) and emerging economy (in blue) IDI scores are not strictly comparable due to different definitions of poverty.

At the bottom of the spectrum lies India, which ranked 62 out of the 74 emerging economies and is the lowest ranked economy from Asia. India has shown improvement over the past five years, mainly benefitting from a low dependency ratio given its very young population, but severe challenges remain. Despite a fall in the poverty rate in India, 60 percent of the population still lives on less than $3.2 a day (at purchasing power parity), and income inequality is a dominant theme. Employment growth remains a key policy challenge in India, despite the strong economic growth the country has witnessed.

Indonesia ranks 36th among emerging economies. While it has dramatically reduced poverty from about 50 percent in 2012 to 33 percent today, wealth remains concentrated in the hands of a few, resulting in a lowly rank of 61 on the inclusion pillar. Indonesia has a Gini coefficient score of 0.84 on a scale of 0 to 1, making it one of the most unequal societies in the world.

Faring better than these two economies is China, which ranks 26th among emerging economies globally. The country has seen rapid economic growth over the past three decades but continues to see high levels of income inequality. However, there has been a rapid reduction in the poverty rate, with the number of people living on less than $3.2 a day falling from about 33 percent in 2012 to just 12 percent today.

Among the region’s advanced economies, Australia fares the best (ranked 9), followed by New Zealand (13), South Korea (16) and Japan (24).*

Policy Implications

The report’s findings indicate that economic growth alone cannot guarantee socioeconomic progress and improve median living standards and that there is a disconnect between GDP growth and inclusion. Of the 30 emerging economies that have seen the strongest GDP per capita growth in the past five years, only six have done as well in terms of improving inclusion, while the situation has remained mediocre in 13 and remained poor in 11.

“Economic growth as measured by GDP is best understood as a top-line measure of national economic performance. Broad, sustainable progress in living standards is the bottom-line result societies expect. Policymakers need a new dashboard focused more specifically on this purpose. It could help them to pay greater attention to structural and institutional aspects of economic policy that are important for diffusing prosperity and opportunity and making sure these are preserved for younger and future generations,” according to Richard Samans, managing director and head of global agenda at the World Economic Forum.

*Singapore is not covered as historical trend data on inclusion-related indicators is not available.