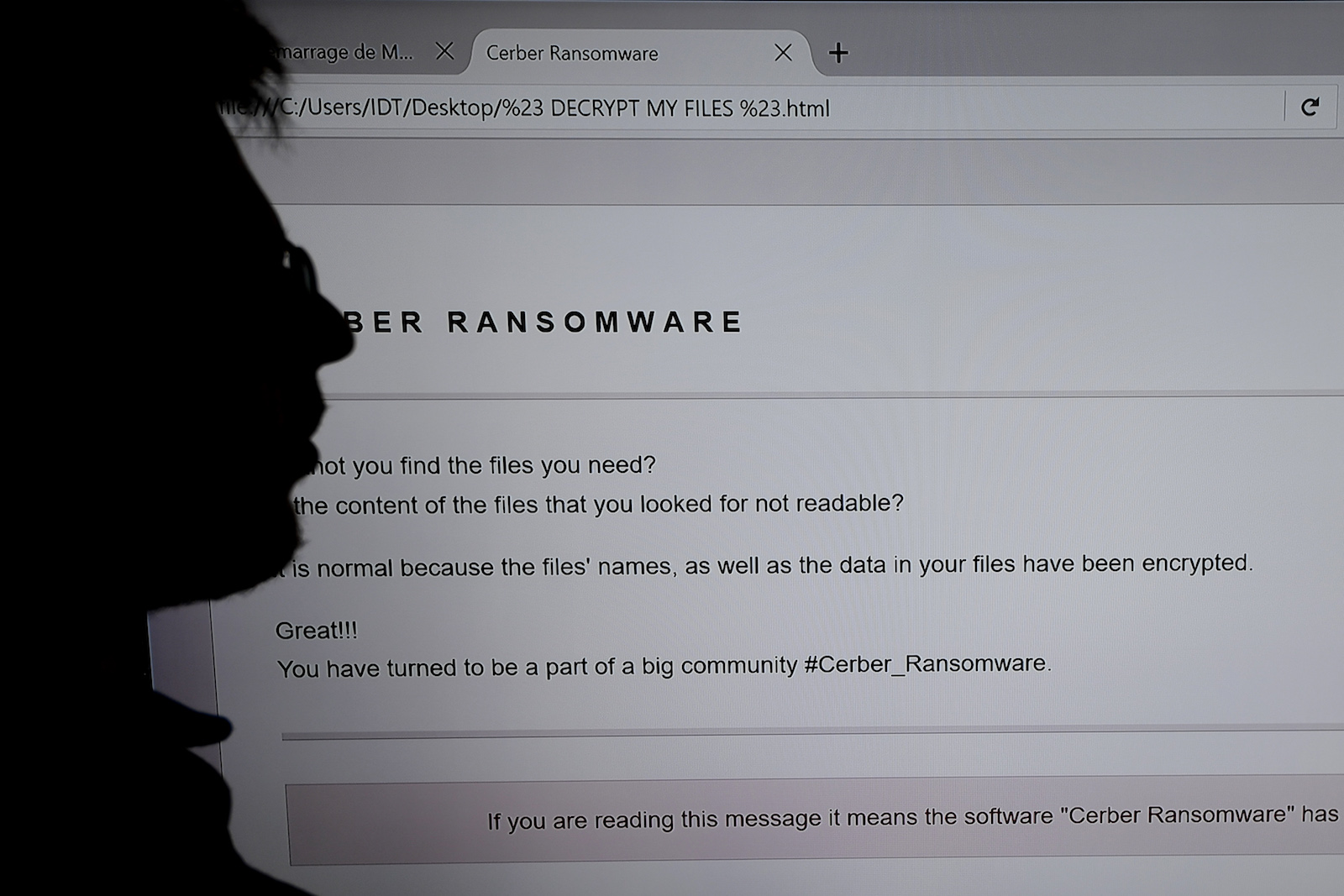

An IT researcher stands next to a giant screen computer infected by ransomware. Organizations need to learn what needs to be done in case something has been stolen, altered or destroyed.

Photo: Damien Meyer/AFP/Getty Images

With the increasing adoption of technology use across businesses, there is an immediate need for region-wide cybersecurity regulations in Asia to counter the threats and risks posed. And while certain regulatory changes have been enacted, companies operating in the region must be prepared to face more change, as we are closer to the beginning than to the end of this trend of increased scrutiny and regulation.

BRINK Asia spoke with Jim Fitzsimmons, director of Cyber Consulting at Control Risks, about the evolving nature of cyber risks and regulations in the region and how businesses are coping with the pressures stemming from both heightened cyber risks and increased compliance and reporting requirements.

BRINK Asia: How is the cyber and data risk landscape in Asia changing?

Jim Fitzsimmons: As more advances are made in technology, more aspects of businesses are becoming digital. More avenues can be targeted by cyber criminals, and they are faced with greater opportunities to find ways of stealing information or IP or indulging in fraudulent transactions. We see an increase in such activities in Asia. Additionally, there are more general risks around ransomware, where malicious software is installed on computers and people are extorted to avoid their personal information being compromised. Asia has generally embraced technology pretty rapidly—both among individuals and companies—and its use has been amplified in the past few years. In keeping with that, we see the cyber risk landscape broadening quickly, and most of it is indiscriminate. We also see more sophisticated targeted attacks against certain companies and sectors.

BRINK Asia: What are your views on the recent SingHealth breach?

Mr. Fitzsimmons: Attacks such as this one underscore what kind of information is considered important and of value to the attacker. Those health records may include all sorts of information that can inform a profile of a Singaporean. In isolation, the health information of one citizen has little value (including that of the prime minister), but in aggregation, that information is very valuable as it can be combined with other information to create a database of profiles on 1.5 million Singaporeans.

These profiles can then be used to develop and deliver personally targeted attacks on Singaporeans via phishing emails, messages, and on social media. No matter who the attackers are—whether cybercriminals or a foreign government—this attack was not the end goal. It was only to gather resources to facilitate more complex attacks.

BRINK Asia: How are companies responding?

Mr. Fitzsimmons: The challenge is that most multinational companies have moved to a more shared services model for various things, including for things such as security. So, systems are heavily centralized, and there are strong governance and security standards in place; these are best practices, and they are good. But the challenge is a company’s operational scope is across many different countries in the region, and many of these issues manifest themselves differently in different countries. In Singapore, for example, you need to make sure that finance people have extra training about anti-phishing. In Thailand, in manufacturing, you need to make sure that digital hygiene—such as downloads and patching, for example—is followed very closely because those are environments that don’t necessarily have long-standing experience in enterprise IT operations or enterprise IT security. If you’re operating in Vietnam, you need to make sure you understand the risks around you, for example, there are numerous unlicensed computers running older versions of Windows. As such, while your computers may have all the necessary patches up to date, the others around are likely to not have them, and with files being sent back and forth via email and people plugging and unplugging USB drives and other such devices, malicious software can easily migrate from one system to another as it is designed to do. It’s like a huge petri dish for malicious software.

The challenge for MNCs is that security is not about one approach; there are different administrative abilities, different functions, and they depend on the markets they operate in. Companies need to make sure they have a country-level view to mitigate risk. Threat actors look for different ways to inflict damage. If they are trying to affect a business in Taiwan, they may go through a sales office in Thailand, for instance. The threat actors are increasingly more sophisticated with strong capabilities.

Most organizations are weak when it comes to responding to breaches. They only realize what needs to be done after an attack happens.

BRINK Asia: What are some of the challenges posed to businesses by evolving cybersecurity laws across Asian countries?

Mr. Fitzsimmons: Regulations around how information is handled are only increasing in breadth and coverage, and this is only the beginning of this trend. Fundamentally, regulations around information handling generally fall into two big buckets—one relates to personal information and data, and the second is around critical digital infrastructure. Some sectors, such as financial services, have been subjected to these regulations for a few years now; and there have been guidelines or regulations on how information is handled in the health care sector in some geographies such as the U.S. Therefore, this is something some industries are familiar with and deal with already on a global basis. For others, however, it is viewed as a hassle. The challenge for these other industries is to now adapt to the new regulations, in terms of allocating resources, manpower and expertise. Most have the capability to deal with these challenges that are being faced or will be faced, but the test for them is that they’ve just begun to get their heads around what the requirements are.

The risk is that the legal requirements are changing quickly, and secondly, there isn’t enough information around them easily available. A lot of companies operating in the region are uncomfortable to report anything to the authorities, because there are no clear guidelines around reporting—so companies could be underreporting or over-reporting. That is a key regulatory risk. It is hard to find out who is the right person to report a breach to, and can it be reported in the right manner? The police sometimes do not respond fast enough in many jurisdictions around the region. We support clients in response cases—we get calls after the barn door has been left open.

China has taken rapid strides in implementing laws around data protection and cybersecurity, but its laws are a challenge for everyone, including Chinese companies. From a policy perspective, it is important for the government. By no means does it want to stifle innovation, but it has rolled out a raft of regulations that companies are struggling to comply with. This is in contrast to Singapore, where the government also regulates, but with lighter touch and more clarity, so that the cybersecurity environment does not become onerous. The Philippines, Hong Kong, Japan and South Korea all have privacy regulations of some kind or another. Many countries have laws in their books, but there are differences in how they are applied. This makes a huge difference.

BRINK Asia: How can businesses in Asia prepare for the regulatory changes being seen/expected?

Mr. Fitzsimmons: The first thing for companies is to understand what information they have and how is this information being regulated? The second is the response to incidents—this goes back to reporting requirements—if a breach of some sort occurs, do you have to report to the police, or some other agency, and what does the reporting and action process look like? Most organizations are weak when it comes to responding to breaches and attacks, and that is only because they realize what needs to be done only when it happens for the first time. Organizations need to be savvier—they need to understand the processes around what needs to be done in case something has been stolen, altered or destroyed. That has always been a best practice in the IP world, but the challenge is that we are reaching a stage where technology is now ubiquitous, and people have not been able to think over all that is really needed.

We would say that this is not just an IT issue, because it involves legal, management and in some cases HR and enterprise risk—various parts of the organization can be impacted by these risks and need to be on the same page in order to respond effectively.

BRINK Asia: Is the lack of harmonization of cybersecurity laws across ASEAN a concern for businesses with operations in multiple jurisdictions?

Mr. Fitzsimmons: Large MNCs with global experience have the resources and operations to manage the differences. For medium-sized companies, however, it can be a challenge because they may not have the resources. They may not be aware of what the requirements are in different countries and are therefore unable to apply them. We are just at the beginning of this trend around regulations and information handling. Governments are responding to this and responding to big data breaches by increasing regulation. The big organizations may have reasonably strong IT teams, but they don’t have teams that understand the regulatory requirements very well. Will that change? Yes. Though I do think we are a long way off from some ASEAN-level regulation yet.