Detecting Bribery of Foreign Officials: An Elusive Pursuit

Demonstrators protest in Sao Paulo, Brazil in December 2016 against corruption.

Photo: Miguel Schincariol/AFP/Getty Images

The number of worldwide prosecutions for bribery of foreign officials is increasing. However, a recent report by the OECD suggests that considerable challenges remain in trying to root out such practices.

The oil and gas industry is the latest to come under prosecutors’ crosshairs. Last year, two Houston-based oil equipment firms agreed to pay the U.S. Department of Justice $660 million for bribery of officials. Next month, two other oil companies will go on trial, alleged to have paid more than $1.1 billion to officials to access an offshore oil field.

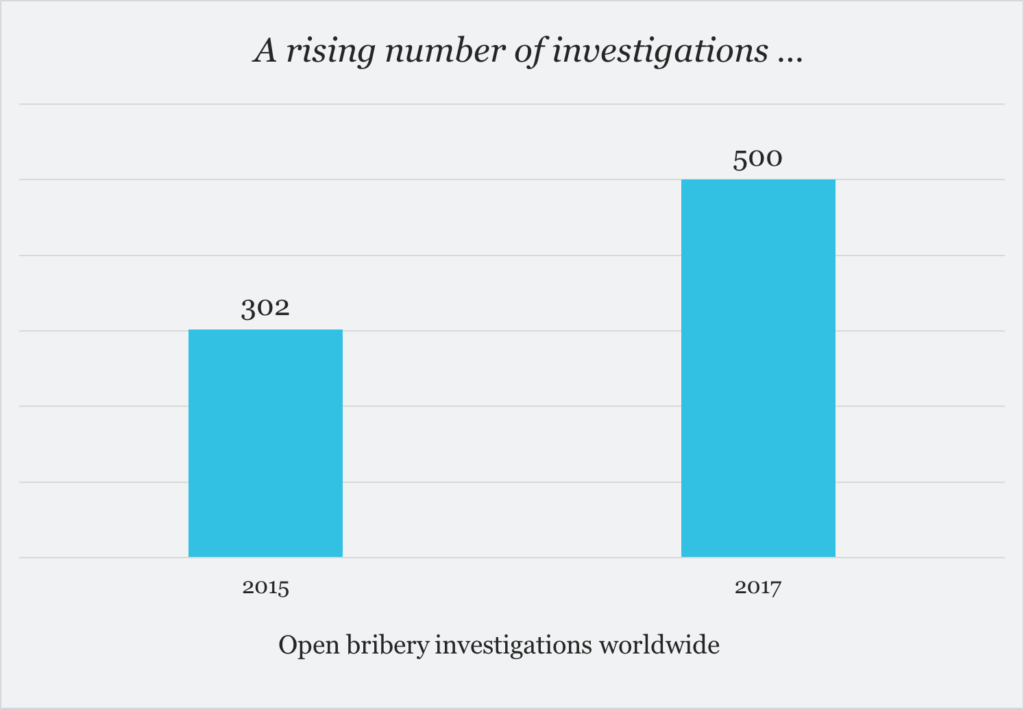

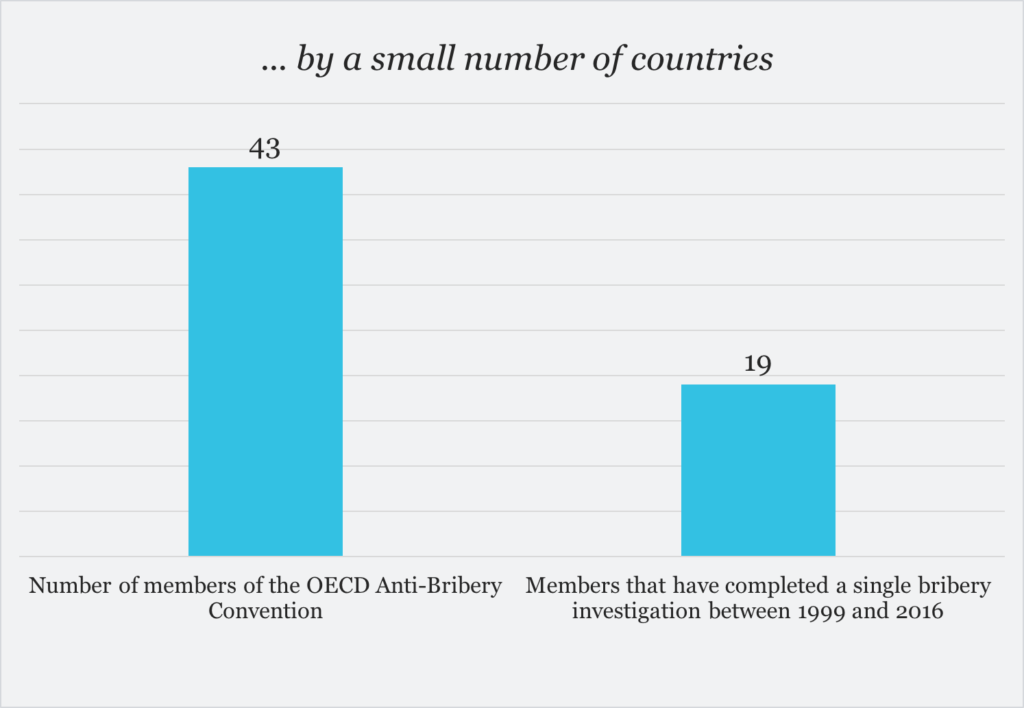

While the number of open bribery investigations has increased sharply over the past two years, fewer than half of the countries that signed the 1999 OECD Anti-Bribery Convention have concluded even a single foreign bribery enforcement action.

Source: OECD, The Detection of Foreign Bribery, 2015 Data on Enforcement of the Anti-Bribery Convention

Tough To Detect

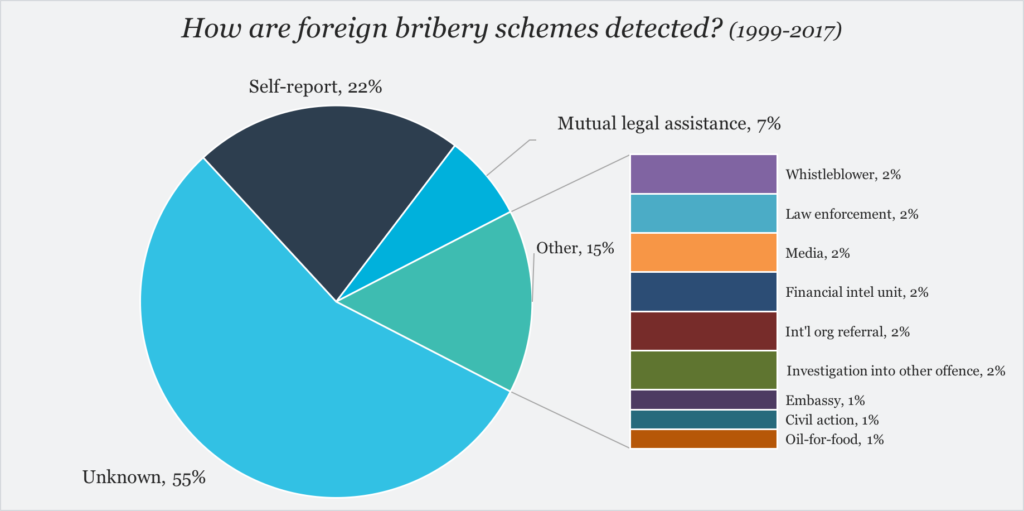

Part of the problem, the OECD acknowledges, is that foreign bribery is extremely difficult to detect. For its report, the organization reviewed hundreds of recent bribery schemes. In most cases, the original source of detection was unknown. The most common known source was self-reporting by the offending company.

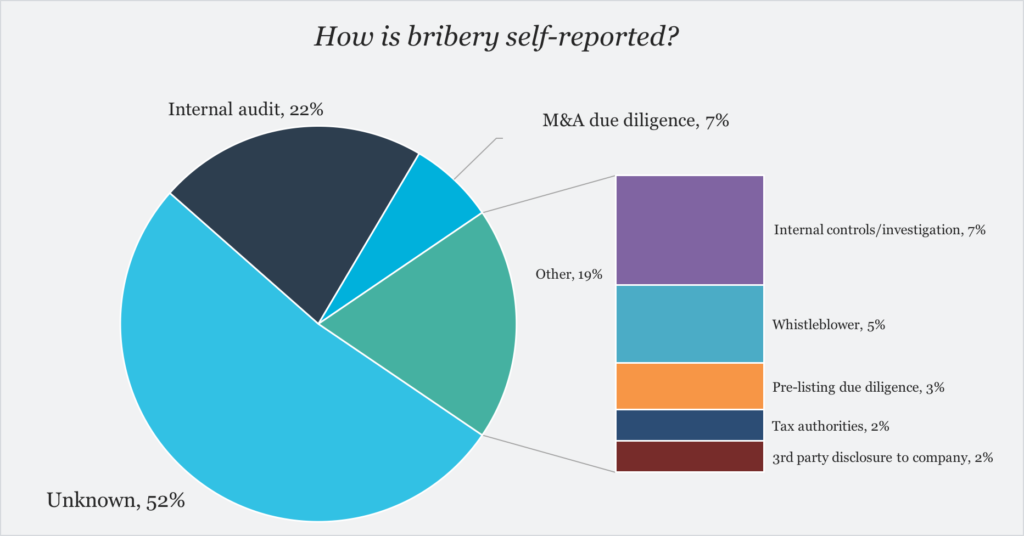

The commonest way for companies to learn about bribery was via an internal audit.

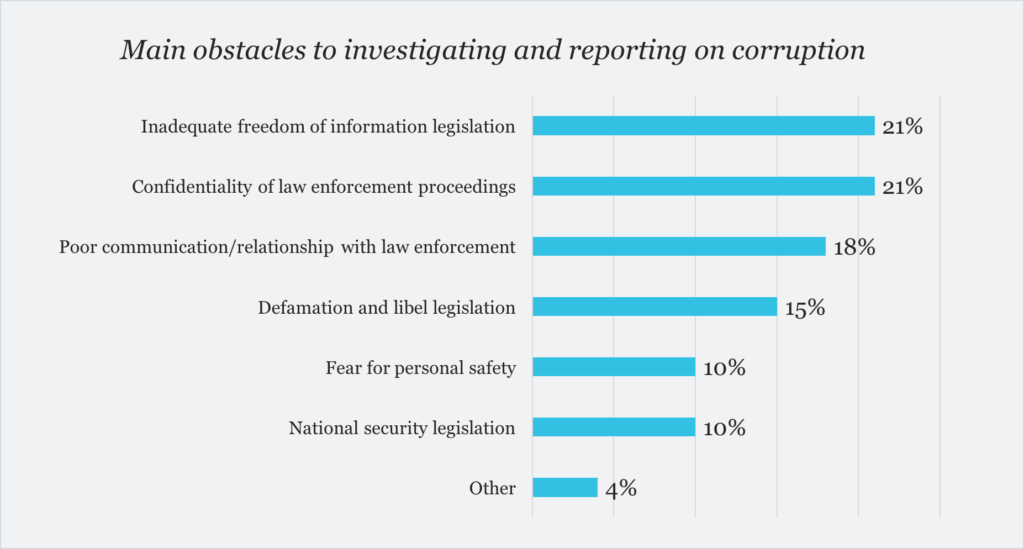

Why isn’t more foreign bribery being detected by entities other than the companies themselves, such as the media, whistleblowers, financial intelligence units and other sources?

The OECD report points to a number of obstacles. For example, in the case of the media, it is often because countries lack adequate freedom of information legislation and inadequate protection of whistleblowers.

Professional advisers such as accountants and legal counsel are in a key position to detect foreign bribery. But these advisers can also be a source of problems. In-house legal and compliance officers are often wary of external legal counsel, who they think can pose a risk of bribery or corruption, usually stemming from their relationships with government officials or the judiciary.

While the OECD report is primarily aimed at policymakers seeking to root out foreign bribery, it also contains recommendations for corporate executives on the question of self-reporting. Among the factors that it says organisations should consider are:

- which jurisdiction to report in

- at what stage in an internal investigation to report to outside authorities

- the possibility of reputational damage if the issue emerges in the media

- the possibility that information provided to authorities may not be protected by legal privilege

- the costs on employees in time and effort

Foreign bribery is hard to detect, the authors say, in large part because “neither the bribe payer nor the bribe recipient has any interest in disclosing the offense.” Most countries have yet to develop the “adequate protection, incentives, and support” required to promote detection by a variety of sources.