Hong Kong and Singapore: The Quest for Regional Education Hub Status

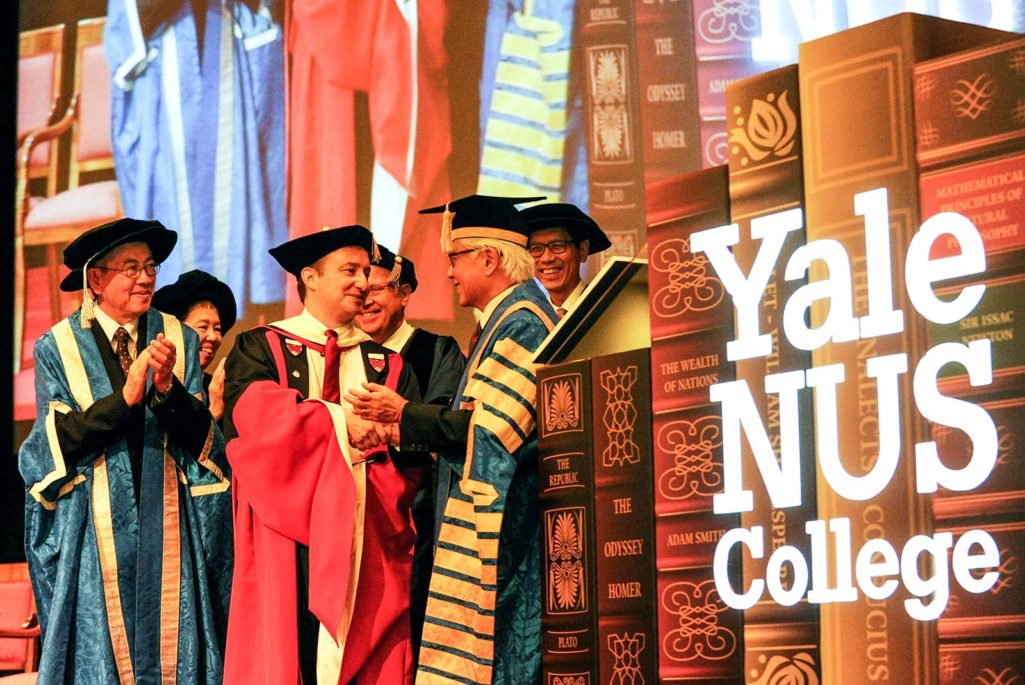

Singapore President Tony Tan Keng Yam shakes hands with Professor Pericles Lewis, president of Yale-NUS college after officiating the inauguration ceremony to mark the start of the Yale-NUS College in SIngapore on August 27, 2013. Yale-NUS College is Singapore's first liberal arts college with a full residential program.

Photo: Roslan Rahman/AFP/Getty Images

Singapore and Hong Kong have long aspired to be regional education hubs and have pursued policies to that effect. However, changing socioeconomic contexts dictate flexible approaches, and how the two states respond to their economies’ evolving requirements will determine their success.

Growing global interdependence within higher education has been recognized for decades, usually seen as “international education” and having its primary manifestations in student and faculty exchanges between countries. Over the last decade, especially after the General Agreement on Trade in Services—which all members of the World Trade Organization are signatories to—came into effect, higher education has been refined in part as a tradable commodity, and the amount of “globalized education” is increasing.

With a strong intention to enhance the competitiveness of their higher education systems, governments across the world, and especially those in Asia, have engaged in the quest to achieve different forms of hub status such as hubs for education, talent and knowledge/information.

As small states in the context of highly competitive knowledge-based economies, Singapore and Hong Kong place particular emphasis on enhancing the quality of higher education for their citizens, especially as improved research capacity and high quality talent will support their standing in the globalizing economy. Nevertheless, it can take a long time for higher education requirements to be fulfilled if only local universities are relied upon. Instead, opening up the education market and allowing leading nonlocal institutions to offer programs or run offshore campuses can act as a catalyst.

To meet its objective of becoming an education hub, the Singapore government has invited foreign universities to set up local campuses and provide more higher education programs. Similarly, the Hong Kong government also encourages overseas universities to offer different kinds of higher education programs in Hong Kong to meet the pressing demand for higher learning, given that the publicly funded universities still maintain a stringent quota of control over student enrollments.

Similar Directions, Different Strategies

While Singapore and Hong Kong are leaders in higher education, the strategies and approaches adopted by the two are different. Aspiring to become the Boston of the East, the Singapore government launched the Global Schoolhouse project about two decades ago. It provides well-articulated policy objectives and strategies by offering handsome packages attracting leading universities/institutions from overseas to develop their campuses in the country.

To assert Singapore’s regional leadership in higher education, the government carefully identifies major gaps and crucial disciplinary areas that Singapore lacks but will need for future development. It then strategically invites world-renowned universities in those fields to set up local programs or campuses. Areas of study that Singapore lagged behind in in the past such as international business and finance, creative arts and culture, and liberal arts education, have been strengthened through partnering and cobranding with leading global institutions. Examples include programs with MIT and Yale universities and an INSEAD campus.

The Singapore government has played a strategic role from planning to implementation in the regional education hub project, appropriately using resources and measures to achieve its policy goals. It has played the role of “market generator,” not only in setting out the strategic direction, but also by proactively orchestrating developments in transnational higher education to meet its national agenda.

The future of Hong Kong and Singapore in education depends on how they adapt to changing socioeconomic contexts.

Meanwhile, the Hong Kong government has been far more committed to free market principles and has taken a hands-off approach, performing the role of market facilitator. Its government has just set out the macro policy direction aspiring to become a regional education hub. However, concrete measures have not been rolled out by the government to achieve such a policy objective. The government believes in the importance of institutional autonomy and academic freedom for universities to run their business and they encourage universities to identify areas and overseas partners to provide programs that could fill the gap and help strengthen Hong Kong’s leadership role in transnational higher education.

Making particular reference to Singapore and Malaysia, critical reviews of the regional education hub project in Hong Kong have revealed no major overseas universities setting up major offshore campuses in the city-state with only a few exceptions, such as the University of Chicago Booth School of Business. Compared to Singapore, and even Malaysia (which has a similar regional education hub project), the project in Hong Kong is more unorganized in terms of comprehensive planning and concrete strategies.

Challenges Ahead

After roughly two decades of experiencing and adjusting to the rapid development of transnational higher education, Singapore and Hong Kong may now have to adopt somewhat different approaches toward one of midlevel state involvement. On the one hand, we may see lesser state intervention in Singapore, and on the other, greater state intervention in Hong Kong may be warranted.

Singapore may need to reduce the state’s role to maintain the vitality and efficiency of its transnational higher education sector. Indeed, in Singapore’s case, there are signs this is already happening. But the Hong Kong government may have to wield its state capacity more proactively in industrializing the sector, so as to make it more conducive to the territory’s economic needs.

The hub projects in these city-states can face challenges when local and regional educational needs start fluctuating. The success and sustainability of these hub projects, for example, depend heavily on the changing political economy context.

In recent times, the Singapore government has faced the dilemma of balancing its Global Schoolhouse aspirations against locals’ complaints of heightened competition for positions at educational institutions. At the same time, Singapore has made policy adjustments not only to the education hub project but also immigration policy, using the education hub project as a policy instrument for the attraction and retention of talent and to supplement its working population. As such, there are different push and pull factors influencing policies relating to the education sector. For example, there were 50,000 foreign students in Singapore in 2002, and while Singapore aimed to draw 150,000 students by 2015, and the number did increase to 97,000 by 2008, it started declining thereafter to reach 75,000 as of September 2014.

Hong Kong, meanwhile, has not given the education hub project such high prominence in its recent policy agendas, especially as the government has placed greater emphasis on meeting its citizens’ housing needs. In fact, recognizing the shortage of land for housing, the government has determined to use land—originally planned for attracting overseas institutions to offer transnational higher education learning in the city-state—as venues for public and/or private housing estates. The hub project has therefore been scaled back, especially as Hong Kong has also experienced a decline in its youth population.

More recently, because students from mainland China—one of the primary sources of foreign students—also have plenty of other options for overseas studies, coupled with challenges related to integrating local and nonlocal students in the city, the government’s push of the education hub project is slowing down.

The future of these two city-states in the global education sector continues to be promising, but only time will tell how well they adapt to the changing circumstances that will influence policies relating to the education sector. How they address these challenges will determine their prospects as regional or even global education hubs in the years to come, and will also have a broader impact on their respective knowledge economies.