How did China Increase the Incomes of its Poor?

Students from the Shaolin Temple Tagou Wushu School form the Chinese flag and slogan which translates as "Win glory for the nation" during their annual spring training at the school in Dengfeng, central China's Henan province on April 7, 2016.

Photo: STR/AFP/Getty Images

While some countries can reduce poverty and fight income inequality, most can achieve just one of these important socioeconomic policy objectives. China is a special case in that it reduced poverty but saw an increase in income inequality over the last two decades.

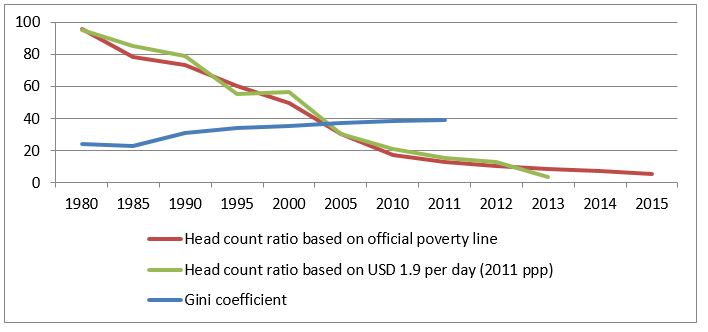

Since 1980, the country has made remarkable progress in reducing poverty. Graphic 1 shows the head count ratio of poverty by the official poverty line, which is about 21 percent higher than the line that is set at USD 1.9 per day (2011 PPP), has been reduced by 94 percent from 1980 to 2015 in rural China.

In contrast, income distribution (the Gini coefficient) among rural residents in China rose by 62 percent, according to official estimates, though it once declined between 1980 and 1985 and was said to decline slightly after 2012.

Change in poverty head count ratio and Gini coefficient in rural China since 1980. Source: China National Bureau of Statistics, the World Bank

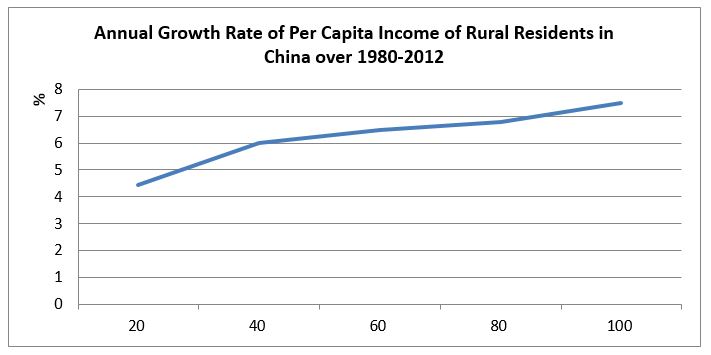

The immediate underlying reason the mismatched change in poverty reduction and income inequality in rural China, however, is not difficult to understand using the growth incidence curve presented in Graphic 2. In the 32 years between 1980 and 2012, per capita net income among the rural population rose by an annual average of 6.9 percent. During those years, the income for the bottom 20 percent and 40 percent of households increased 4.5 percent and 6 percent each year, respectively, while the top quintile of households increased their income at an annual rate of 7.5 percent.

Growth incidence curve of income per capita in rural China over 1980-2012. Source: Author’s own calculation based on data from China’s National Bureau of Statistics.

It is clear that the marked reduction of poverty in rural China is because the bottom households increased their income at a high annual rate over a long time. On the other hand, income inequality had been rising largely because the top quintile of households had increased their income much faster than their poor counterparts.

But how did the bottom 60 percent of households in rural China increase their income at a considerably high rate over such a long period? There are at least four factors underlying the income growth of the poor.

First, the benefits of China’s sustained economic growth have trickled down. Accelerating industrialization and urbanization in a country of over one billion people has transformed a large number of the agricultural surplus labor in the countryside into urban employment in China.

Between 1978 and 2015, the number of people in nonfarm jobs as a percentage of total employment increased from 29 percent to 70 percent. This change also occurred in poor areas and to poor households. Official data indicates that while the number of those that moved away for nonfarm jobs, as a percentage of the total size of the local labor populations, was slightly lower in poverty-stricken areas than in the nation as a whole, the gap between the growth rates of the number of people shifting to nonfarm jobs in poor areas, and in the nation as a whole, was reduced nearly to zero for the period between 1996-2009.

Between 2002 and the end of 2012, earnings from wage and salaries as a percentage of total household income rose from 26 percent to 43 percent for rural households in the bottom 20 percentile, at a rate that was roughly comparable to the national average. Evidently, low-income rural households have benefitted proportionally from the changes in the country’s employment pattern, engendered by the dual process of industrialization and urbanization.

Second, the system of land ownership has notable consequences for both the occurrence and the mitigation of poverty in rural China. The distribution of cultivated land in rural China has been more proportionate, with bottom quintile households owning about 90 percent of land areas as the top quintile owned, much more balanced than income and consumption per capita. On average, each of the bottom quintile households owns 0.6 hectare of cultivated land. The relatively equal distribution of land enables the bottom poor to proportionally benefit, not only from development and reform in agriculture, but also from the transfer payments the state provids to support agricultural development.

Third, universal social development programs made contributions to the income growth of the bottom households. China has implemented a couple of social development programs in rural areas since 2000, including universal compulsory education up to grade nine, rural medical cooperative system, social pension system for rural residents, and a minimum living allowance scheme. With these programs in place, low income households secured a share of benefits larger than their part in other sources of income, which helps the poor increase their disposable income at a higher rate than that of their productive income. Official data indicates that increased transfer income for the bottom quintile households between 2002 and 2012 contributed 21 percent of their increased disposable income during the period.

Finally, targeted poverty reduction programs, in place nationally since 1986, played an important role. The Chinese government launched a package of targeted poverty reduction programs covering broad areas, from physical infrastructure and social development, to industrial development and income generation to assist poor households and poor areas and improve their ability to share the benefits of national growth and generate more income by themselves. An incomplete official statistic shows that earmarked funding input from central government totaled 469 billion yuan (~US $70 billion) between 1980 and 2016.

Given the central government’s commitment to ending extreme poverty by 2020, one can gather that going forward these programs will make a larger contribution to poverty reduction in China, with the introduction of more precise poverty reduction interventions.

This piece first appeared on East Asia & Pacific on the Rise, a World Bank blog.