It’s Past Time to Build Better Mental Health in the Construction Industry

A worker prepares an area for a concrete pour at a the site of a new housing development in San Francisco, California. Construction workers continue to pay a price due to the industry’s outdated attitudes toward mental health.

Photo: Justin Sullivan/Getty Images

In the dwindling list of industries that maintain a macho, male-dominated culture, construction is certainly near the top. One unfortunate consequence is that construction workers continue to pay a price due to the industry’s outdated attitudes toward mental health.

Given that May is Mental Health Awareness month in the United States and elsewhere, it’s an appropriate time to take a look at some of the issues facing the construction industry. Thankfully, mental health is starting to come to the fore in conversations around construction. Contractors, developers and civil engineers are committing themselves to increasing their workers’ well-being. It’s not a moment too soon.

Construction’s Poor Mental Health Record

Globally, the construction industry has one of the worst records for employee mental health and suicides. In the United Kingdom, for example, about 400 workers in the construction and engineering sectors take their own lives each year.

Construction suicide rates globally were described as alarming in the 2017 conference paper, Suicide in the Construction Industry: It’s Time to Talk. The paper detailed that, in many countries, the suicide rates for those in the building trades were higher than the general population.

Several risk factors combine to make construction such a damaging profession for worker mental health. They also present challenges to organizations attempting to effect changes, including:

- Construction’s workforce is predominantly male, and despite some changes, still retains a traditional, macho “don’t-ask-for-help” culture. Consider that the most common cause of death for men aged 20 to 49 years in England and Wales is suicide, according to the UK Mental Health Foundation. The higher risk factor for males is amplified by construction’s “don’t-ask-don’t-tell” approach to mental health issues.

- Construction is a tough job that has the potential to trigger and exacerbate anxiety and depression, with long hours, irregular pay and working conditions that have traditionally been cold and dirty. Additionally, the job’s “hire-and-fire” nature can leave workers worried about their ability to support themselves and their families.

- Bullying is another factor. Employees who experience workplace bullying are twice as likely to experience suicidal thoughts, according to the Workplace Bullying Institute. In construction, about 60 percent of employees experience bullying.

- The lack of support networks is also an important element. Working in the construction industry can involve a lot of long-distance travel and extended time spent away from families, friends and other support networks.

In the UK, 1,419 construction employees took their own lives between 2011 and 2015, with low-skilled male construction workers having the greatest risk, at 3.7 times the national average. Indeed, workers in the building trade are six times more likely to take their own life than be killed in a fall from height. Employees in the building finishing trades—including plasterers, painters and decorators—have a risk twice the national average.

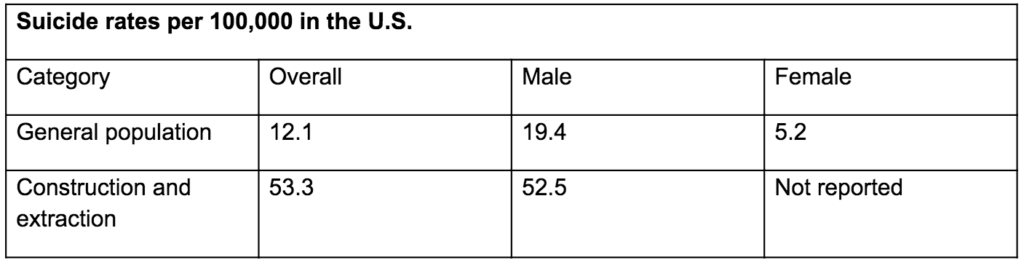

In the U.S., suicide rates are highest among men in the construction and extraction (mining) sectors, according to a 2018 report from the Centers for Disease Control. In Canada, suicide is the second leading cause of death in the construction industry in men aged 25 to 59, with the highest rates in male workers aged between 40 and 59.

In Australia, construction workers are 70 percent more likely to take their lives than males employed in other industries in Australia. Builders, laborers and operators have an elevated risk of suicide. Each year in New Zealand, about 75 percent of all suicides in the country are committed by men, with those of working age being the most vulnerable. Construction workers are more at risk than any other employed men in the country, working in a culture on site that has been described as macho, bullying and intolerant of diversity.

Business Concerns

Failure to address mental health issues can, first off, lead to poor outcomes for workers. If stress becomes excessive and prolonged, mental and physical illness may develop. High job demands increase a worker’s odds of being diagnosed with a medical condition by 35 percent, and if they consistently work more than 40 hours a week (perhaps to meet those high demands), they are almost 20 percent more likely to die a premature death.

For a company, there are additional considerations. At minimum, stress, anxiety and poor mental health within a construction firm’s workforce can result in falling productivity, worker absence and poor staff retention rates. Beyond that, employers’ liability and other legal issues can stem from a failure to attend to workers’ mental health.

In England, for example, courts have held that employers can be liable for a suicide and its financial effects if they are found to be in breach of duty for an original physical injury or bullying/harassment that led to the depression that triggered the suicide. In such cases, it is common for a civil claim to be launched by the family or dependents. Additionally, employers might also be found liable for breaches of health and safety law, resulting in regulatory unlimited fines, publicity notices and even prison sentences for individuals convicted of gross negligence manslaughter.

Employers must also be aware of the possibility for insurance claims to made against them related to suicide and mental health issues. Currently, the number of employers’ liability (EL) claims against contractors’ or developers’ insurance is low, relative to the amount of suicide-related deaths within the construction workforce. Employers should be mindful that the statistics could be higher than published figures due to the difficulty of ascertaining whether an on-site death was suicide or an accident.

The increased potential of claims—coupled with developments in the way the “chain of causation” is interpreted and the developing duty of care owed by an employer—means the issue of workplace suicide could result in a future increase in EL claims and payouts.

The Benefits of Good Mental Health in Construction

Globally, the construction industry’s governing bodies are introducing initiatives to boost mental health and provide advice and support to workers who are in distress. While the level of uptake varies from country to country, construction firms are getting with the program. They are beginning to destigmatize mental health issues and discover ancillary benefits that could avert future deaths, while also reducing the legal, financial and reputational considerations that inevitably flow from such tragedies.

Construction companies that adopt a progressive approach to worker mental health are putting themselves on the front foot, both legally and morally.