Most People in Asia Now Living Longer, Healthier Lives

A hospital staff member escorts a patient at the Beijing Friendship Hospital during a government supervised media tour on February 29, 2012. The tour aimed to showcase improved hospital facilities and highlight the progress of country-wide healthcare reforms.

Photo: Ed Jones/AFP/Getty Images

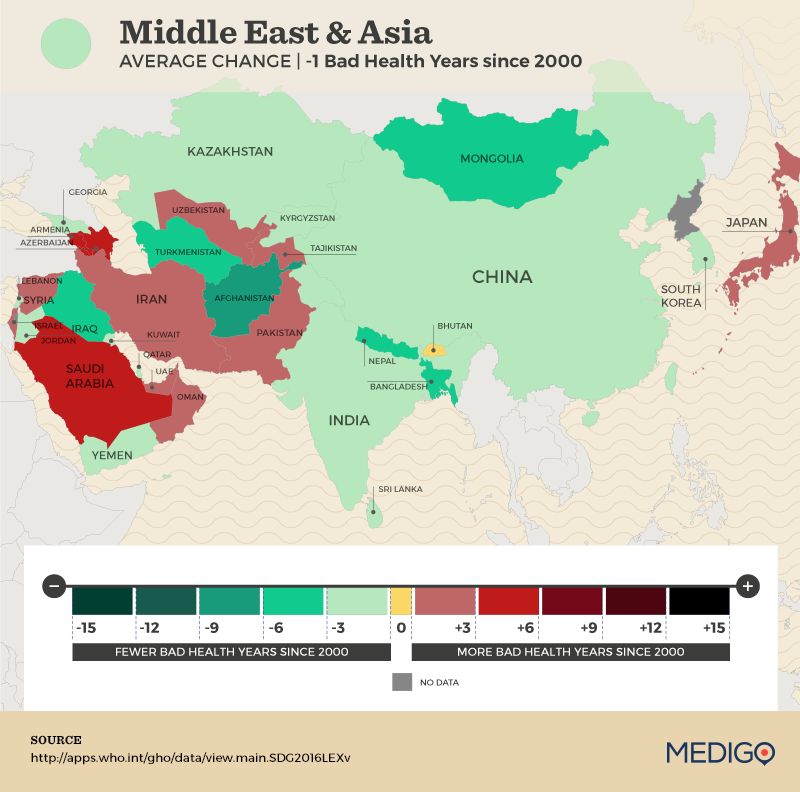

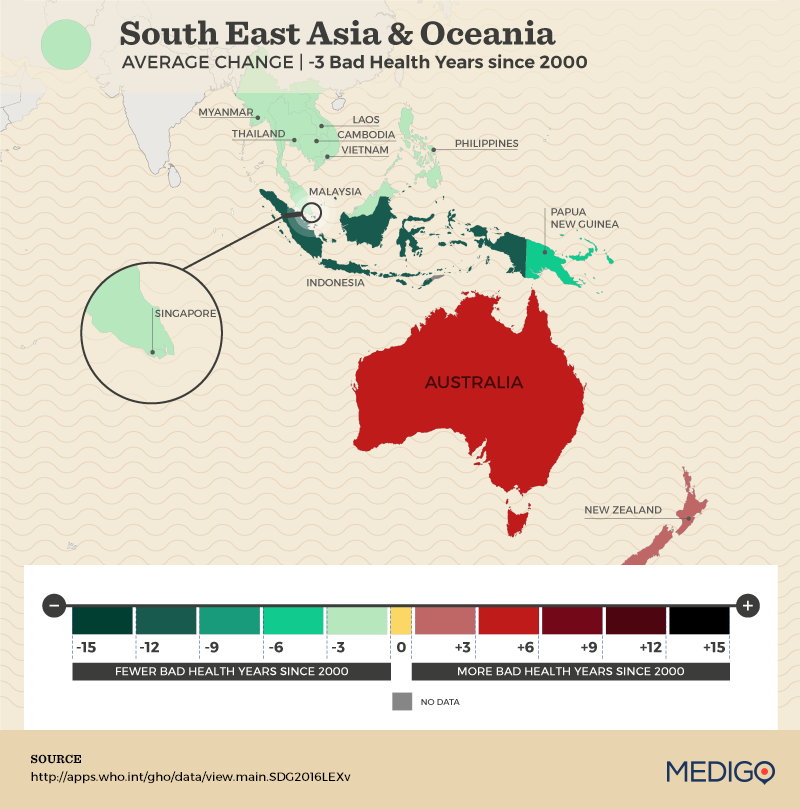

Since the turn of the 21st century, many Asian populations have seen a significant increase in life expectancy and a decrease in the number of years they can expect to live in bad health. This is in stark contrast to much of Europe and North America, where the number of years lived in ill health has increased since the year 2000. These findings are part of a recent study on the concept of “bad health years.”

What are Bad Health Years?

The average life expectancy of a human being is the highest it has ever been and will continue to rise in coming years. By 2030, the average female born in South Korea can expect to live to an astonishing 91 years of age. After seeing these studies on our increasingly longer lives, a deeper look at the idea of life expectancy and what this means for health is warranted.

Healthy life expectancy (HALE) is a metric used by the World Health Organization to define how many years a person will live without disease or disability, taking into account social, economic and political factors, as well as rates of disease. By subtracting healthy life expectancy from actual life expectancy, we see the number of years lived in bad health. The most interesting part of this analysis is the change in the number of bad health years since the year 2000, which reveals that most citizens in Asia are now living healthier lives.

The reasons behind the decrease in bad health years are complex and multifaceted and can vary dramatically country-by-country. But there are several general regional trends that help explain why populations in Asia are living fewer years in bad health.

Disease Prevention

Prevention of disease is arguably the primary factor that influences the number of years people live in bad health. One of the foremost causes of disease in the developing world is the lack of adequate sanitation, with diarrheal diseases among the leading causes of child mortality in the Asia-Pacific region.

It is estimated that 564 million people in India still openly defecate, exposing people to bugs and harmful bacteria that can lead to intestinal illnesses. Despite this, India has made huge strides toward bringing down the number of deaths caused by diarrhea and other related diseases caused by poor hygiene. In 2004 around 535,000 child deaths in India could be attributed to diarrhea. In 2015, an estimated 117,000 Indian children were killed by the disease. While this is still a shockingly high number, the slow push toward greater sanitation and hygiene education is having a positive effect on bad health years in the country. On a global scale, deaths caused by diarrhea are projected to decrease by six percent between now and 2030.

Access to Health care

Access to health care can also reduce bad health years. In 2012, the United Nations passed a resolution on Universal Health Coverage, stressing “the importance of universal access to health services for saving lives, ending extreme poverty, building resilience against the health effects of climate change and ending deadly epidemics.”

Many nations in Asia have made steps toward universal health coverage in recent years. China embarked on a series of health reforms in 2009, and while there have been a number of initial problems, it is now estimated that around 96 percent of the population has access to health insurance. Put into perspective, only 21 percent of China’s rural population had health insurance in 2003.

In Southeast Asia, Indonesia introduced a universal system of health coverage in 2014, and the Philippines and Vietnam have begun putting similar systems in place. Although these systems are far from perfect, improvements in accessibility to health care have no doubt contributed to the decrease in bad health years.

Paradoxically, in some cases, greater access to health care could see bad health years increase in future. When people receive treatment that suppresses disease but does not cure it, they will still live more years in bad health.

Economic Development

Economic development is another key factor in the reduction of bad health years. Between 2002 and 2013 alone, the number of people in Asia living in extreme poverty (on less than $1.90 a day, in purchasing power parity terms) fell by 707 million. In the same period, the number of people living on under $1.90 a day in South Asia alone declined by almost 300 million (from 36 percent of the population to 16 percent); In East Asia, the number stands at just 1.8 percent. The rise of the middle class across Asia is one of the defining demographic shifts of the 21st century.

This is primarily owing to free-market reforms, industrialization, greater education, few military conflicts, and advancements in science and technology, among other factors. Poverty alleviation is accompanied by a rise in living standards, removing people from environments that could potentially lead to them living in bad health due to lack of shelter or adequate sanitation, and providing people with the opportunity to improve their diet and nutrition.

Future Challenges

While most of Asia is seeing fewer bad health years, outcomes elsewhere are less than favorable. In the world’s most developed regions, such as Europe and North America, bad health years have increased on average since 2000. It is important to note that these regions already have some of the highest life expectancy in the world.

As life expectancy increases in these regions, so too do bad health years. This is most likely due to lifestyle factors resulting in people living a greater proportion of their lives with disease or disability, which raises an interesting question: Can Asia prepare now for the challenges that increasing life expectancy and living standards will bring?

In 2010, heart disease was the fourth biggest killer in Southeast Asia. By 2030, however, heart disease will have overtaken pneumonia, stroke and tuberculosis to become the number one cause of death in the region. Deaths caused by heart disease will also increase in the Middle East and Pacific regions. Changes in lifestyle, owing to further economic growth and demographic shifts, will play a huge role in these increases.

The reduction of bad health years in Asia since the start of the new millennium is a fantastic achievement. The big challenge now is maintaining this level of social and economic progress while at the same time avoiding the increase in bad health years found in Europe and North America.