Reopening Schools Too Early Could Spread COVID-19 Even Faster — Especially in the Developing World

Students wear face masks while a teacher writes on the board in Central Africa in August 2020. COVID-19 deaths in Africa are likely to be severely undercounted due to a lack of COVID-19 testing and unreliable data on deaths generally.

Photo: Arsene Mpiana / AFP via Getty Images

According to the latest UNESCO figures, more than 100 countries are currently implementing nationwide school closures due to COVID-19, affecting more than 60% of the world’s enrolled students. The topic of reopening primary and secondary schools has been heavily politicized in many countries, with parents, teachers and politicians sometimes at odds over when to reopen. Policy decisions are even more challenging given the lack of evidence, especially from developing countries, on how susceptible children are to contracting COVID-19 and transmitting the virus to adults and how to make schools safe enough for students to return.

What we do know is that low-income countries face a different set of circumstances from high-income countries: a higher proportion of households include both children and elderly people, there is difficulty in testing for COVID-19 and enforcing social distancing in existing school settings and there is an urgency in maintaining the livelihoods of working-age adults to prevent hunger and poverty. Our study found that reopening schools too early in developing countries could undermine the gains made so far in containing the spread of the virus. When deciding to reopen schools, policymakers need to weigh these findings against the cost of keeping schools closed for a prolonged period.

We use an economic model that reflects how developing economies differ from advanced economies: They have younger populations; there is more contact between people at home, work, and school; large informal sectors make lockdowns harder to enforce; and there is less fiscal and health care capacity. We find that age-targeted policies (shielding those over 65 and those with severe underlying medical conditions) are the most effective in saving lives and preserving livelihoods.

In Developing Countries, Reopening Schools Significantly Increases the Risk of Spreading COVID-19

A common justification for reopening schools is that children are unlikely to die from COVID-19. Yet, children live with adults and, particularly in developing countries, some of these adults are elderly. According to United Nations data, the proportion of elderly people who live with at least one child under 20 is more than 10% in most African countries, compared to less than 1% in European countries and the United States. This raises the risk that children may contract the virus at school and transmit it to parents and grandparents at home.

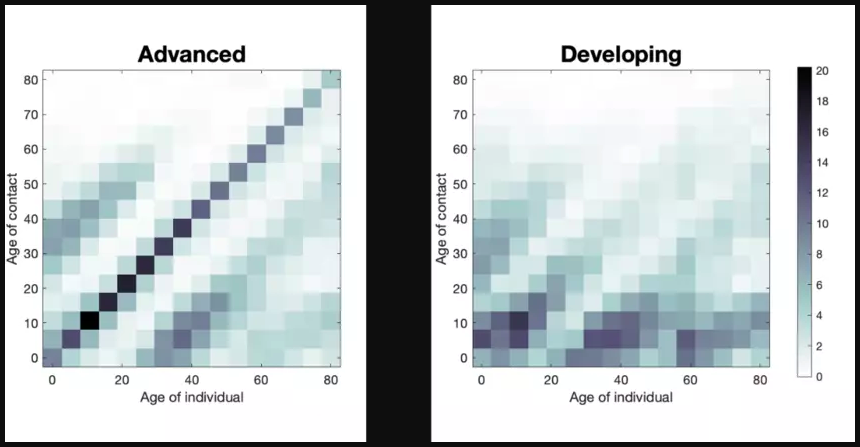

In developing countries, adults and the elderly generally have more contact with children than those in advanced economies due to factors such as more crowded living conditions and bigger households. The darker shaded region on the lower right corners of the figures show that the number of contacts between older adults (age 60-80) and children (under age 20) is substantially larger (darker) in developing countries.

Contact Patterns at Home, Advanced and Developing Economies

Source: How Should Policy Responses to the COVID-19 Pandemic Differ in the Developing World? The National Bureau of Economic Research; Notes: Cohabitation patterns are more crowded in developing countries. The pronounced diagonal entries in the advanced economy’s matrix highlights this point; most people in advanced countries live with others in the same age group — the elderly tend to live separately from younger generations, interacting with them only intermittently.

Our study compares a few scenarios to look at the effect of schools reopening on COVID-19 infection rates and deaths in Nigeria, Africa’s most populous country. While speculative, this simulation gives us a tool to compare the impact of different policy measures in a large developing country. Furthermore, the overall predictions are applicable to many other low-income countries, which share the feature of large families living under one roof, with frequent contact between the young and their older household members. Throughout, we calibrate our economic model based on fatality rates estimated in the famous Imperial College report and a study in Spain suggesting that children get infected by COVID-19 at about two-thirds the rate of adults.

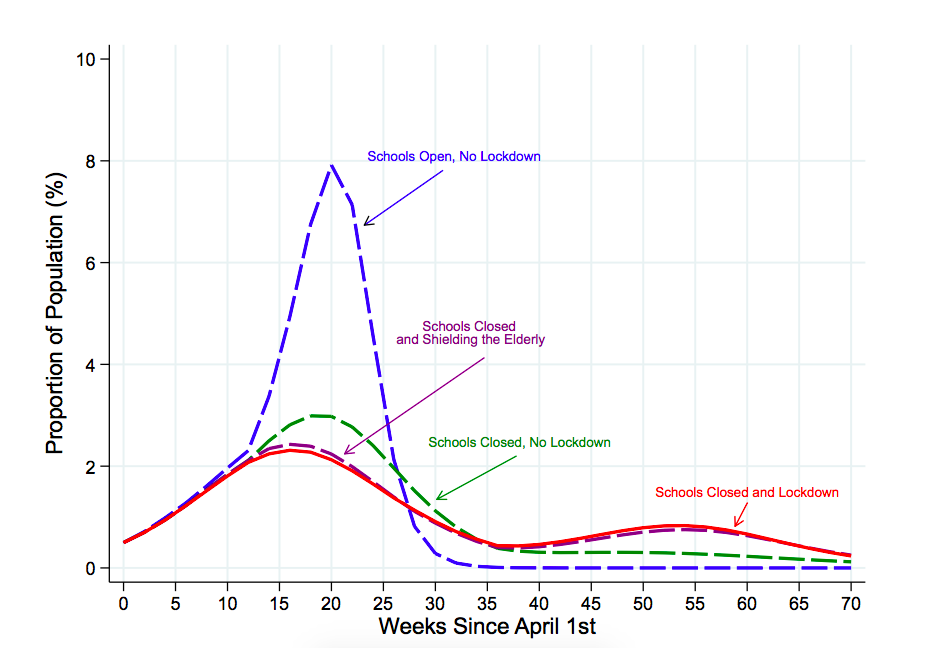

The graph below shows the proportion of the population infected by COVID-19 under four policy scenarios.The blue dashed line simulates the effects of an immediate school reopening; this leads to a large increase in infections. The other scenarios simulate the effects of delaying school reopenings until January 2021; these lead to much flatter curves. We find the most effective policy option (illustrated by the purple dotted line) to control infection rates while avoiding a blanket lockdown is to delay schools reopening until January 2021 while shielding the elderly.

School Closures and Aggregate Infection Dynamics

Source: How Should Policy Responses to the COVID-19 Pandemic Differ in the Developing World? The National Bureau of Economic Research; Notes: The most effective policy option (illustrated by the purple dotted line) to control infection rates while avoiding a blanket lockdown is to delay schools reopening until January 2021 while shielding the elderly.

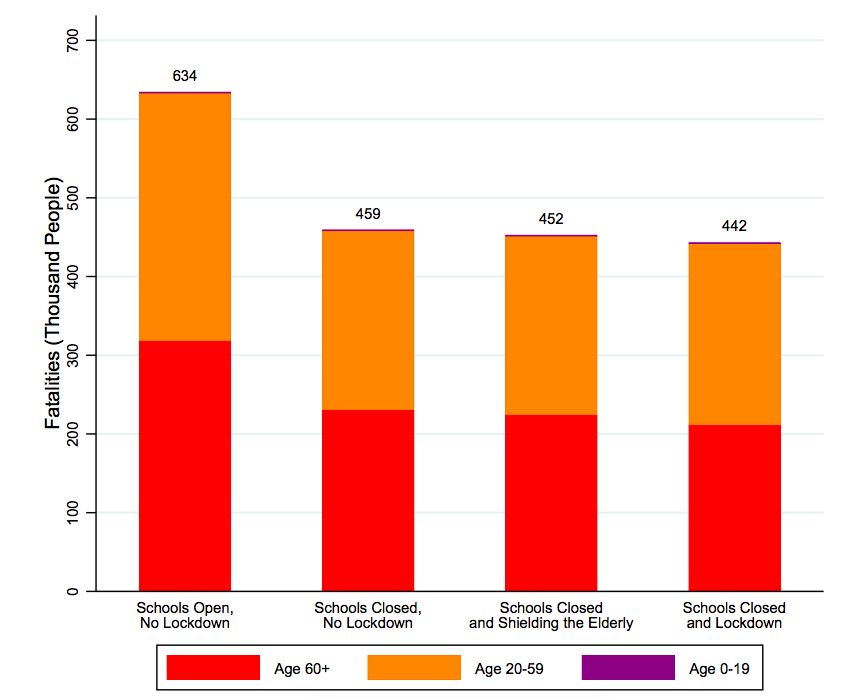

The figure below shows the total number of deaths predicted by our model under the same scenarios. The large fatality numbers are based on the Imperial College study and do not match up to current reported numbers from Nigeria. Though all models are based on assumptions, making perfect predictions impossible, COVID-19 deaths in Africa are likely to be severely undercounted due to lack of COVID-19 testing and unreliable data on deaths generally.

The figure illustrates the breakdown of fatalities by age group. Our model predicts less than 0.1% of deaths in any scenario are children. Opening schools increases fatalities among older adults — and most commonly the elderly. By closing schools alone, our model predicts it could save around 175,000 lives relative to doing nothing. Other additional interventions can do even better, such as shielding the elderly. A blanket lockdown (of the formal sector) would save the most lives, but would lead to large additional declines in GDP, meaning reduced livelihoods for many vulnerable households.

Simulated Deaths by Age Under 36-week School Closure in Nigeria

Source: How Should Policy Responses to the COVID-19 Pandemic Differ in the Developing World? The National Bureau of Economic Research; Notes: This figure plots the number of deaths in total and by age group predicted by the model under various simulations about school closings and lockdown policies.

In all scenarios, the model suggests only modest additional gains in terms of lives saved from delaying school reopenings past January 2021, predicting Nigeria will have achieved substantial herd immunity by then. In the case of closing schools and shielding the elderly, for example, our model predicts that just under half of the population will have been infected by the start of 2021. This is similar to recent studies of COVID-19 prevalence in Mumbai’s slum areas. The biggest gains from school closures come from delaying reopenings this fall with a plan to reopen early the following year.

What About the Costs of Not Reopening Schools?

The single biggest reason to delay school reopenings is to help stop the spread of COVID-19. Our study predicts that delaying school openings can be a potent force for saving lives by reducing the risk of children getting infected at school, and in turn, spreading the virus within their households.

Of course, any policy decisions about delaying school openings must weigh the potential lives saved against the negative impacts of keeping children out of school for a long period. Major issues of concern in developing countries around keeping schools closed for long periods include losses in learning, missed midday meals, availability of childcare for working parents and limited resources for online learning.

While our study does not address all the issues related to schools reopening during the pandemic, we argue that evidence on household spread of the virus needs to be considered by governments when deciding to reopen schools.

A version of this article originally appeared in the World Economic Forum’s Agenda Blog.