The Missing Link: Financial Development and Technology in Southeast Asia

This picture shows a general view of traffic as Manila's financial district is seen in the background.

Photo: Noel Celis/AFP/Getty Images

Over the past three decades, the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) region has become an important destination for foreign direct investment (FDI) as companies and investors have sought to capitalize on a growing market, and as the regional economies have become more embedded in global production chains. At the same time, the persistent current account surplus in the region indicates that domestic savings exceed domestic investments, and therefore the region is exporting capital to the rest of the world.

The Investment Flow Paradox

Key ASEAN economies such as Singapore, Malaysia and the Philippines, for example, have maintained current account surpluses from 2003 to 2015. In fact, over the past few years, the six largest ASEAN countries, with the exception of Indonesia, have largely recorded current account surpluses far more often than not.

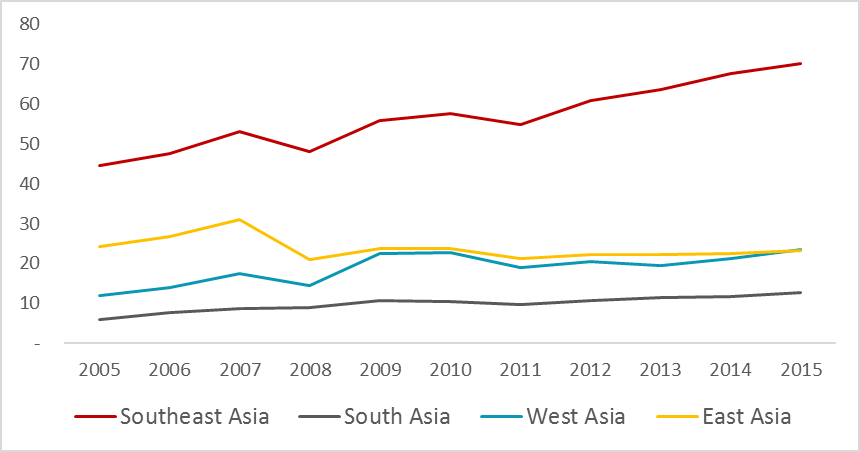

The ASEAN economies heavily rely on FDI as a source of capital. Compared to other parts of Asia, the ratio of inward FDI stock to GDP in the region remains high and has been climbing. In 2015, it reached 70 percent (Exhibit 1). Singapore, Thailand and Malaysia are the three largest recipients of FDI in the region.

Exhibit 1: Inward FDI stock as a percentage of gross domestic product

In short, Southeast Asian economies typically run a current account surplus but receive large amounts of FDI at the same time. This is puzzling. Why is it that the region relies so much on foreign savings (inward FDI) when there is an abundance of domestic savings (current account surplus)?

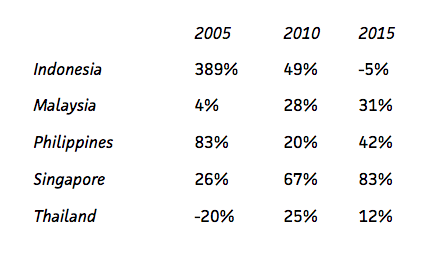

According to the data, a large proportion of domestic savings flow out of ASEAN in the form of foreign portfolio investment (FPI), and is thus invested in foreign financial assets such as stocks and bonds. Popular destinations for portfolio investment are the U.S. and Europe.

Exhibit 2: FPI net outflow as a percentage of current account balance

The constant inflow of FDI into Southeast Asia indicates abundant investment opportunities and growth potential. Paradoxically, a current account surplus combined with an FPI outflow reflects a lack of domestic investment opportunities in financial assets.

This paradox can be unpacked by presenting a link between financial development and technological progress.

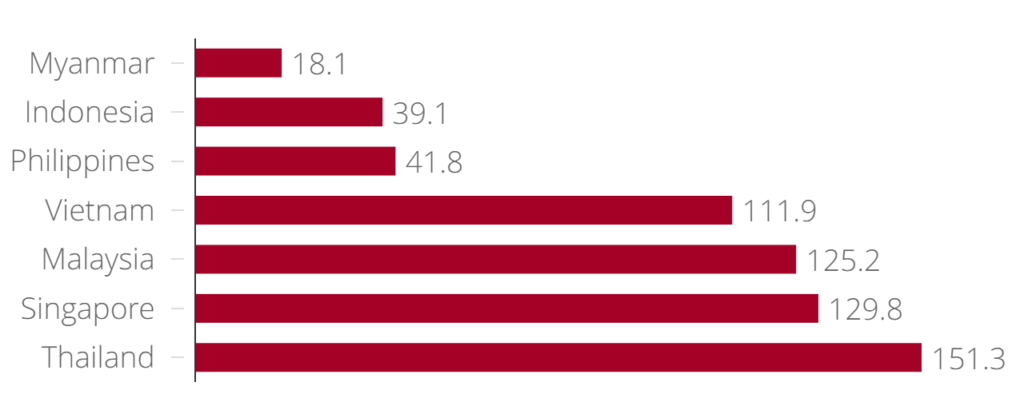

The level of financial development in Southeast Asia varies from country to country. While Singapore stands out as a financial hub, countries such as Myanmar, Indonesia and the Philippines are severely underbanked and underfinanced. The underdeveloped financial markets in the region cannot channel the excess savings into domestic investment, whereas developed markets such as the U.S. and Europe can absorb the excess savings. For example, in Myanmar, Indonesia and the Philippines, domestic credit to the private sector constitutes just 18.1, 39.1 and 41.8 percent of GDP respectively, compared to 188.9 percent in the U.S and 97.9 percent in the EU.

Exhibit 3: Domestic credit to private sector (as a % of GDP, 2015)

Extra ASEAN FDI inflows comprised more than 80 percent of total FDI inflows into the region from 2013 to 2015. Around half of the inflows are from advanced economies and target investments in ASEAN for labor-intensive production, to secure natural resources, and to tap into the growing regional markets. On the other hand, the host countries expect the FDI to contribute to technological transfer and industrial restructuring.

According to the United Nations Conference on Trade and Development, 80 percent of international trade today takes place in global value chains (GVCs) linked to multinational corporations (MNCs). Most Southeast Asian economies specialize largely in low-risk and labor-intensive production and occupy the low value-added segments of GVCs. To manage and operate the GVCs, MNCs need to reduce trade costs and hedge various risks associated with clearing and settling trade. Therefore, they are unlikely to expand the high value-added operations of the GVCs to Southeast Asia in the absence of a more developed financial market. This hints at a link between technology and financial development in Southeast Asia.

To achieve technological progress, a country can either breed its own technological innovation by intensive R&D investment, or transfer foreign technologies home through trade and FDI. What we observe is that both channels don’t work sufficiently without a developed financial market.

Southeast Asian economies could attract more MNCs and benefit directly from technology spillovers if its financial markets were more developed. R&D investment, workforce training and education would spur local innovation and strengthen the spillover effect. Finally, more MNC activities and investment in technology and innovation would broaden investment opportunities for both financial and non-financial assets. The excess savings in the region can then be better utilized for investment within the region. Moreover, financial development can complement and reinforce technological progress and vice versa.

Despite the increasing importance of Asia in international trade, the huge FPI outflow to U.S. dollar-denominated assets reflects the dominance of the U.S. dollar in regional trade settlement, financial transactions and portfolio investment. As a result, high exchange risks and transaction costs hinder the promotion of Asian financial markets. More investment, finance and banking in local currencies will reduce the exchange rate risks and transaction costs, although the size of the market matters.

Coming Together

United efforts to promote local currency financing were made after the Asian Financial Crisis in 1997, involving the ASEAN grouping and others. For example, the ASEAN +3 countries (China, Japan and South Korea) launched the Asian Bond Markets Initiative to develop Asian bond markets in 2002. Since then, local bond markets have grown significantly.

The ASEAN +3 Macroeconomic Research Office (AMRO), which is an international organization based in Singapore, has strengthened the regional financial cooperation of the Chiang Mai Initiative Multilateralization—a multilateral currency swap arrangement between ASEAN +3 members.

That notwithstanding, regional cooperation in Asia is a complex issue as illustrated by recent events. For example, the Trans-Pacific Partnership excluded China, while Japan is reluctant to join the China-initiated Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank. While political and security issues between China and Japan complicate their bilateral relations, Sino-Japan cooperation—which is seen in multilateral groupings such as ASEAN +3—will only help to create a more efficient regional financial system that is beneficial to ASEAN and the wider Asia-Pacific region as a whole.