What Kind of High-Income Country will Malaysia Become?

The skyline of Kuala Lumpur from the observation deck of the KL Tower. Malaysia is becoming a center for sustainable investment.

Photo: Mohd Rasfan/AFP/Getty Images

Malaysia is no longer stuck in the middle-income trap, given the steady growth of its gross national income (GNI). Malaysia’s GNI per capita in 2015 was $10,570. It is just short of the World Bank’s benchmark of $12,475 per capita for high-income nations and should achieve this by 2020. Yet, Malaysia is confronted with one key question—what type of high-income country will it be?

Will resource-rich Malaysia, like South Korea, be a progressive liberal democracy where high incomes are sustained by innovation-induced productivity based on strong human capital development, or one that relies on revenue growth from natural resources, such as Saudi Arabia?

Comparing Malaysia to these two economies provides an idea about the kind of high income country it could become in the next few years.

Components of Growth (2010-2015)*

In 2015, South Korea was the 11th largest economy in the world (1.89 percent share of the world economy), Saudi Arabia was ranked 20th (0.86 percent share of the world economy) and Malaysia 33rd (0.43 percent).

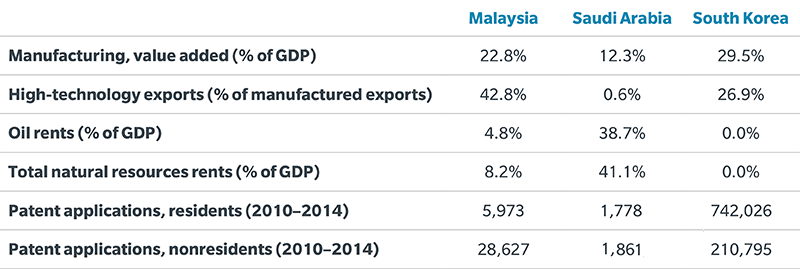

In Saudi Arabia, the manufacturing sector’s value add as a percent of GDP peaked at just 12.3 percent in 2015, while high-technology exports contributed less than 1 percent of the country’s manufactured exports, illustrating a lack of innovation and productivity improvements.

However, total natural resources rents as a percent of GDP in Saudi Arabia stood at 41 percent in 2014. Though lower than the 52 percent in 2011, it was still relatively very high. Similarly, oil rents as a percent of GDP fell from 49 percent in 2011 to 39 percent (still high) in 2014.

In South Korea, the value added from the manufacturing sector hovered at about 30 percent between 2011 and 2015, and high technology exports constituted around a quarter of the manufacturing exports. Not surprisingly, South Korea derives no revenue from resources or oil.

It is clear that these two countries stand in contrasting positions when considering the chief contributors to economic growth. While Saudi Arabia depends on natural resources, South Korea depends on high technology exports and greater value added.

Malaysia currently finds itself somewhere in the middle of these two divergent examples. In 2015, the country’s manufacturing sector value added was 23 percent of GDP. Strikingly, high-tech exports accounted for 43 percent of its total manufacturing exports. Malaysia has also been gradually reducing its reliance on resources as a source of growth, with natural resources rents as a percentage of GDP declining from 11 percent in 2010 to 8 percent in 2014, and oil rents as a percent of GDP decreasing from 6 percent in 2010 to 4.8 percent in 2014.

The Malaysian economy’s structure is transitioning toward that of South Korea with high-tech exports and services.

Links with Innovation and Human Capital Development

South Korea had 6,899 researchers and 1,241 technicians in R&D per million people, while Malaysia had 2,052 researchers and 212 technicians per million people, respectively (there was no data available on the number of researchers and technicians in R&D for Saudi Arabia). This illustrates that Malaysia still has a long way to go to catch up with South Korea in terms of its R&D human capital and skills capabilities.

The issue is exacerbated given that while South Korea invested 4.3 percent of its GDP toward R&D in 2014, Malaysia invested just 1.2 percent. For Malaysia to move toward more innovation-led growth, it needs to increase its expenditure on R&D and education.

Similarly, the total number of patent applications registered in Saudi Arabia in 2010-2014 was by far the lowest among the three countries in question. In the same period, Malaysia saw a total of 34,600 patent applications, whereas the number of patents in South Korea was a whopping 27 times greater.

Where is Malaysia Headed?

These numbers provide a clear illustration that Malaysia needs to do a lot more if it is to become a high-income country in the footsteps of South Korea. It needs to increase expenditure on R&D and promote human capital development, both of which will be critical to its economic performance.

The Malaysian economy’s structure is transitioning toward that of South Korea with high-tech exports and services being on par with South Korea. Yet, Malaysia is certainly not investing in its human capital in the same way that South Korea has done; and in terms of outcomes of innovation (as measured by patent applications), Malaysia is far behind South Korea. For example, patent applications submitted by Malaysian residents were only 1 percent of those submitted by South Korean residents.

At the same time, Malaysia does not have the luxury of relying on natural resources rent as Saudi Arabia has done and cannot afford to support high levels of income through social transfers.

In fact, Saudi Arabia, too, is trying to step away from its resource-driven growth model, cognizant of its limitations. In October, Saudi Arabia’s Public Investment Fund teamed up with Japan’s SoftBank to create a $100 billion technology-investment fund that could become the world’s biggest tech investment in the coming decade.

This is one of the initiatives to support the country’s “Vision 2030” plan, according to which, the country is looking to raise non-oil revenue to $160 billion by 2020 and $267 billion by 2030. In 2015, non-oil revenue contributed only $43.6 billion.

It will be interesting to see whether Malaysia’s government will go the desired way of innovation-driven growth as it leads the country’s economic reform, or whether Malaysians will accept high income alone as a final outcome.

* All data from World Development Indicators.