Collaboration, Research are Keys to Successful Integration of Commercial Drones

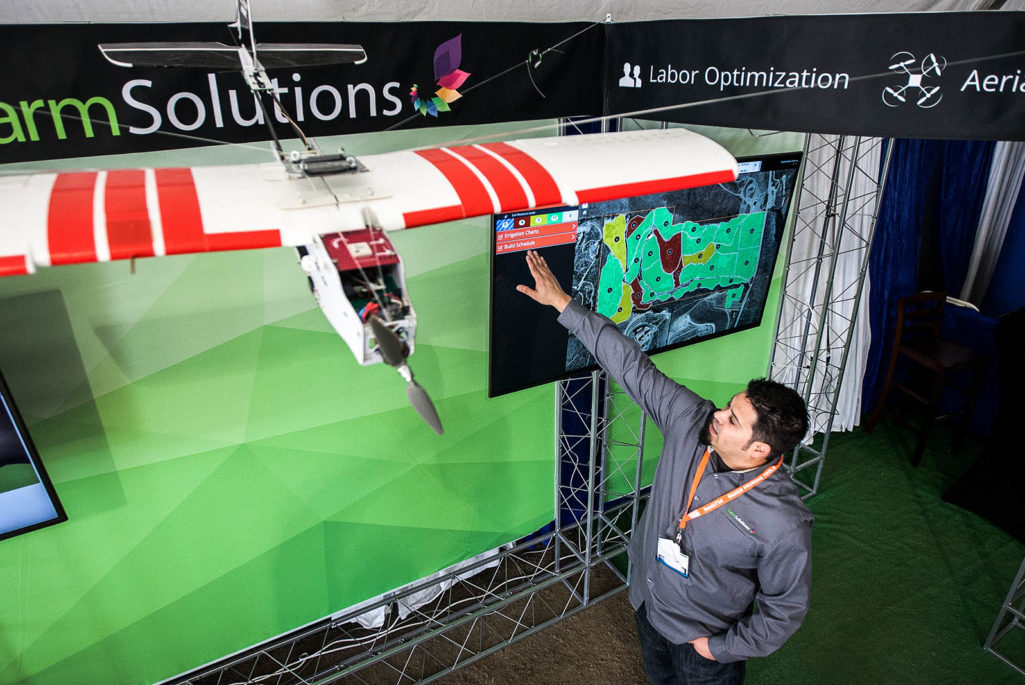

A drone hangs above Vincent Rodriguez as he explains how it can be used to monitor field health at the FarmSolutions exhibit on opening day of the World Ag Expo on February 10, 2015 in Tulare, California.

Photo: David McNew/Getty Images

The U.S. aerospace industry is on the brink of a revolution that will have almost nothing to do with airlines and everything to do with Unmanned Aircraft Systems (UAS), popularly known as “drones.”

Within ten years the drone market will create 104,000 new jobs. The economic impact of drone integration into the U.S. airspace will total more than $13.6 billion in first three years, growing to a total of $82 billion between the years 2015 and 2025, according to a report from the Association for Unmanned Vehicle Systems International.

Estimates for drone operations over the next two decades sound like science fiction. In a 2013 U.S. Air Force report public sector drone use was estimated at 55,000 by 2035, up from the roughly 2,000 flying in the national airspace (NAS) today, jumping to a staggering 175,000 unmanned systems within 20 years. The Department of Defense estimates it will be operating 18,000 drones by 2035, up from 8,000 today, with over half of all military aircraft flying with UAS technology.

While the military has been successfully operating drones for more than a decade in the areas of intelligence, surveillance, and reconnaissance, the U.S. commercial and public sectors are in a holding pattern due to the ongoing development of rules allowing for their commercial operations. In 2012, Congress mandated the Federal Aviation Administration (FAA) to develop a plan to safely integrate civil drones into U.S. airspace and to establish operational and certification requirements for public use by 2015.

Progress has been careful but slow. At the end of 2013, the FAA selected six public entities as official UAS research and development test sites. This past February, the FAA released its proposed rules that would allow routine use of certain small, unmanned aircraft systems in today’s airspace, while “maintaining flexibility to accommodate future technological innovations.”

Still, most UAS insiders are concerned that the FAA will not meet the 2015 deadline and that the adoption of final rules may still be years away. The U.S. has led the world in the development of drone technology, but many in the industry feel the country is falling behind in their use. A National Public Radio report in December noted that several European countries have granted commercial permits to more than 1,000 drone operators for safety inspections of private infrastructure such as railroad tracks or to support commercial agriculture.

Australia issues permits to businesses engaged in using drones for aerial surveying, photography and other activities and makes allowances for such flights in lightly populated areas. Small, unmanned helicopters have been used to monitor and spray crops in Japan for more than a decade. Canada recently revised its regulations to grant blanket permission for flights of drones weighing less than five pounds and loosened restrictions on UAS up to 55 pounds.

“We’re going to miss out on the capabilities, benefits and advantages this technology can bring if we don’t start to understand how it can best be leveraged,” says Brent Bowen, Embry-Riddle professor and dean of the College of Aviation. Bowen warns that some U.S. companies are not waiting for the FAA: “U.S. companies are leaving to go [to] places like Mexico, Brazil, the Philippines and Japan to fly their devices.”

Up to now, only public entities could apply for an FAA Certificate of Authorization (COA) to operate UAS although it is now possible for organizations to apply for an exemption to allow for commercial use. The only other authorized users are hobbyists. Private organizations must partner with a public entity with an approved COA or acquire an exemption in order to operate drones legally. Other alternatives are to fly drones through student clubs or test larger aircraft with a pilot in the cockpit.

Drone Integration Issues

The slow integration of drones into U.S. airspace may be a good thing. “People are really worried about privacy and safety,” says Richard Stansbury, Embry-Riddle associate professor of computer engineering and computer science and coordinator of the Master of Science in Unmanned and Autonomous Systems Engineering program. “The worry is if it opens up too quickly and there is a major disaster, it could set the whole unmanned aircraft industry back.”

Waiting on the FAA isn’t necessarily a bad thing, because it gives industry leaders time to consider the unintended consequences of the technology, says Anke Arnaud, an ethicist and associate professor of management at Embry-Riddle. Arnaud supports careful consideration of any new technology that could adversely affect people or the environment. She is not alone. There are plenty who worry about drone use in law enforcement and its capability to invade personal privacy.

“Recent public discourse on privacy being breached by the government has delayed public acceptance of UAS and fueled a sense of paranoia,” says Stansbury. While he believes the paranoia is unfounded and that there is adequate case law related to surveillance from helicopters and remote cameras that can apply to UAS technologies, Stansbury acknowledges that “a helicopter hovering above you is something you can tell is there. These unmanned aircraft have the ability to blend in very well with the sky, especially because they’re very small and very quiet.”

The privacy issue should be moot, says Charlie Reinholtz, Embry-Riddle professor and department chair of Mechanical Engineering. “I believe its phones, not drones, that we need to be worried about,” he says, while noting that privacy in America is largely an illusion, given the abundance of cell phone cameras and location services, as well as public video cameras monitoring everything from traffic to security.

According to Ken Witcher, Embry-Riddle Worldwide Dean of College of Aeronautics, most people, if asked, would not give up their cell phone even if there is a privacy or security risk; the value of cell phone technology is clearly understood.

“The public perception challenging small UAS operators is due to the lack of perceived value,” Witcher says. “Once UAS are able to reduce the cost of delivering fresh products, provide real-time traffic updates to reduce your commute, reduce the amount of chemicals we use in U.S. agriculture, find lost hikers quicker and cheaper even in weather conditions manned aircraft could not safely operate in; the value of this technology will become evident,” says Witcher. “To do this, we need to educate and train a new type of operator; one who understands the U.S. aviation safety culture and how to operate within the national airspace system, but also understands how to apply this technology in non-traditional roles.”

“Drone terrorism,” however, is another story, Reinholtz says. “There are hobbyists that clearly have the ability to build an autonomous aircraft that can fly several miles and hit a target for less than $1,000. And everything you need to do that can be purchased off the Internet and nobody is monitoring it,” he says. “That’s a pretty significant potential concern.”

Regardless, Reinholtz says there’s no stopping it. “This is pervasive technology, whether it is unmanned autonomous aircraft or cars, it’s really the same,” Reinholtz says. “It is starting to surround us and people have no idea. It’s here. It’s coming. It’s going to continue to come,” he says. “[And] from a liability viewpoint, you can’t ignore technology that’s going to save lives.”

Stansbury is optimistic for the future of UAS, given his role in managing the Embry-Riddle team at the FAA Center of Excellence that will be the technical lead in UAS airport ground operations, and co-lead in UAS pilot and crew training and command and communication research. “Embry-Riddle helped develop the ASSURE Coalition to create the best collaboration between academia and industry to support research in unmanned aircraft systems,” says Stansbury. “We are eager to begin working with the FAA to solve these technical challenges by conducting research that quickly, safely and effectively gets UAS flying alongside manned aircraft around the world.”