How Is Working From Home Working Out?

Although COVID-19 has battered the economy, things would have been far worse without the ability to work from home. Working from home is not only economically essential, it is a critical weapon in combating the pandemic.

Photo: Unsplash

This is the first of two pieces about how working from home is changing the employment landscape. The second piece was published on September 1st.

Working from home is dominating our lives. If you haven’t experienced the phenomenon directly, you’ve undoubtedly heard all about it, as U.S. media coverage of working from home jumped 12,000% since January 1.

But the trend toward working from home is nothing new. In 2014, I published a study of a Chinese travel company, Ctrip, that looked at the benefits of its work-from-home policies. And in the past several months, as the coronavirus pandemic has forced millions of workers to set up home offices, I have been advising dozens of firms and analyzing four large surveys covering working from home.

The recent work has highlighted several recurring themes, each of which carries policy questions — either for businesses or public officials. But the bottom line is clear: Working from home will be very much a part of our post-COVID economy. So the sooner policymakers and business leaders think of the implications of a home-based workforce, the better our firms and communities will be positioned when the pandemic subsides.

The US Economy Is Now a Working-From-Home Economy

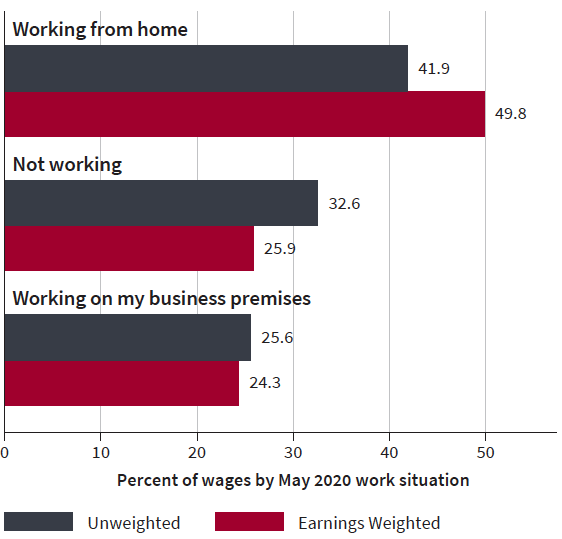

Figure 1 shows the work status of the 2,500 Americans that my colleagues Jose Barrero (ITAM), Steve Davis and I surveyed between May 21-25. The responders were between the ages of 20 and 64, had worked full time in 2019 and earned more than $20,000. The participants were weighted to represent the U.S. by state, industry and income.

We find that 42% of the U.S. labor force are now working from home full time, while another 33% are not working — a testament to the savage impact of the lockdown recession. The remaining 26% are working on their business’s premises, primarily as essential service workers. Almost twice as many employees are working from home than at a workplace.

If we weight these employees by their earnings in 2019 as an indicator of their contribution to the country’s GDP, we see that these at-home workers now account for more than two-thirds of economic activity. In a matter of weeks, we have transformed into a working-from-home economy.

Although the pandemic has battered the economy to a point where we likely won’t see a return to trend until 2022, things would have been far worse without the ability to work from home. Remote working has allowed us to maintain social distancing in our fight against COVID-19. So, working from home is not only economically essential, it is a critical weapon in combating the pandemic.

Figure 1: Working From Home Now Accounts for Over 60% of U.S. Economic Activity

The Inequality Time Bomb

But it is important to understand the potential downsides of a working-from-home economy and take steps to mitigate them.

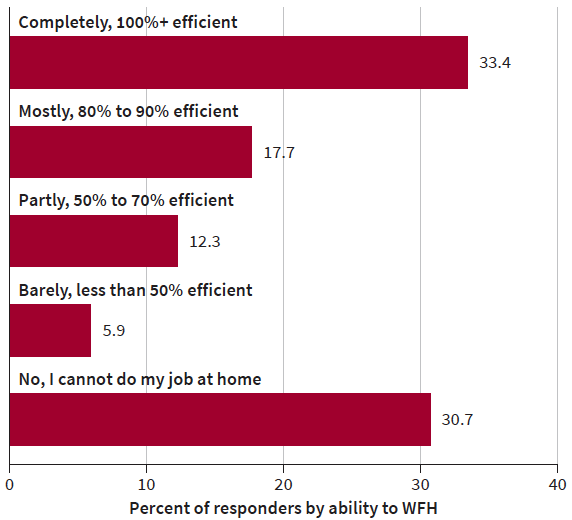

Figure 2 shows not everyone can work from home. Only 51% of our survey respondents reported being able to work from home at an efficiency rate of 80% or more. These are mostly managers, professionals and financial workers who can easily carry out their work on their computers by videoconference, phone and email.

The remaining half of Americans don’t benefit from those technological workarounds — many employees in retail, health care, transportation and business services cannot do their jobs anywhere other than a traditional workplace. They need to see customers or work with products or equipment. As such, they face a nasty choice between enduring greater health risks by going to work or forgoing earnings and experience by staying at home.

Figure 2: Not All Jobs Can Be Carried Out Working From Home

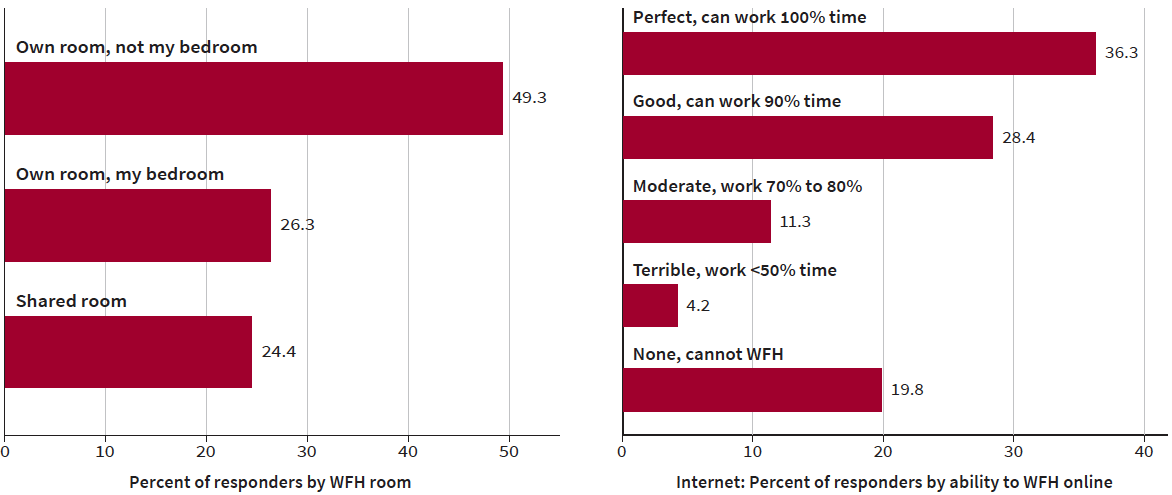

In Figure 3, we see that many Americans also lack the facilities to effectively work from home. Only 49% of responders can work privately in a room other than their bedroom. The figure displays another big challenge — online connectivity. Internet connectivity for video calls has to be 90% or greater, which only two-thirds of those surveyed reported having. The remaining third have such poor internet service that it prevents them from effectively working from home.

Figure 3: Working From Home Under COVID-19 Is Challenging for Many Employees

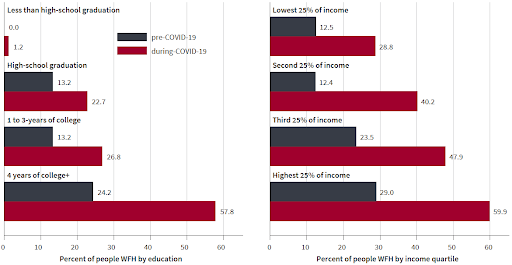

In Figure 4, we see that educated, higher-earning employees are far more likely to work from home. These employees continue to earn, develop skills and advance careers. Those unable to work from home — either because of the nature of their jobs or because they lack suitable space or internet connections — are being left behind. They face bleak prospects if their skills erode during the shutdown.

Taken together, these findings point to a ticking inequality time bomb.

Figure 4: Working From Home Is Much More Common Among Educated Higher-Income Employees

So as we move forward to restart the U.S. economy, investing in broadband expansion should be a major priority. During the last Great Depression, the U.S. government launched one of the great infrastructure projects in American history when it approved the Rural Electrification Act in 1936. Over the following 25 years, access to electricity by rural Americans increased from just 10% to nearly 100%. The long-term benefits included higher rates of growth in employment, population, income and property values.

Today, as policymakers consider how to focus stimulus spending to revive growth, a significant increase in broadband spending is crucial to ensuring that all of the United States has a fair chance to bounce back from COVID-19.

Trouble For Cities?

Understanding the lasting impacts of working from home in a post-COVID world requires taking a look back at the pre-pandemic work world. Back when people went to work, they typically commuted to offices in the center of cities. Our survey showed 58% of those who are now working from home had worked in a city before the coronavirus shutdown, and 61% of respondents said they worked in an office.

Since these employees also tend to be well-paid, I estimate this could remove from city centers up to 50% of total daily spending in bars, restaurants and shops. This is already having a depressing impact on the vitality of the downtowns of our major cities. And, as I argue below, this upsurge in working from home is largely here to stay. So I see a longer-run decline in city centers.

The largest American cities have seen incredible growth since the 1980s as younger, educated Americans have flocked into revitalized downtowns. But it looks like 2020 will reverse that trend, with a flight of economic activity from city centers.

Of course, the upside is that this will be a boom for suburbs and rural areas.