Working From Home Is Here to Stay

People stand on designated squares in an elevator to ensure social distancing. Strictly enforcing six feet of social distancing, could decrease the maximum capacity of elevators by 90%.

Photo by Ivan Damanik/AFP via Getty Images

This is the second of two pieces about how working from home is changing the employment landscape. Part 1 was published on August 31, 2020.

Working from home is a play in three parts, each totally different from the other. The first part is pre-COVID. This was an era in which working from home was both rare and stigmatized. A survey of 10,000 salaried workers conducted by the Bureau of Labor Statistics showed only 15% of employees ever had a full day working from home. Indeed, only 2% of workers ever worked from home full time.

Often Stigmatized

Working from home before the pandemic was also hugely stigmatized — often mocked and ridiculed as “shirking from home” or “working remotely, remotely working.” In a 2017 TEDx Talk, I showed the result from an online image search for the words “working from home” which pulled up hundreds of negative images of cartoons, semi-naked people or parents holding a laptop in one hand and a baby in the other.

Working from home during the pandemic is very different. It is now extremely common, without the stigma, but under challenging conditions. Many workers have kids at home with them. There’s a lack of quiet space, a lack of choice over having to work from home and no option other than to do so full time. Having four kids myself, I have definitely experienced this. COVID-19 has forced many of us to work from home under the worst circumstances.

Working From Home Post Pandemic

But working from home post-COVID-19 should be what we look forward to. Of the dozens of firms I have talked to, the typical plan is that employees will work from home between one and three days a week and come into the office the rest of the time. This is supported by our evidence on about 1,000 firms from the Survey of Business Uncertainty that I run with the Atlanta Fed and the University of Chicago.

Before COVID-19, 5% of working days were spent at home. During the pandemic, this increased eightfold to 40% a day. And post-pandemic, the number will likely drop to 20%. But that 20% still represents a fourfold increase of the pre-COVID level, highlighting that working from home is here to stay. While few firms are planning to continue full-time WFH after the pandemic ends, nearly every firm I have talked to has been positively surprised by how well it has worked.

The Office Will Survive, But It May Look Different

“Should we get rid of our office?” I get that question a lot.

The answer is “No. But you might want to move it.”

Although firms plan to reduce the time their employees spend at work, this will not reduce the demand for total office space given the need for social distancing. The firms I talk to are typically thinking about halving the density of offices, which is leading to an increase in the overall demand for office space. That is, the 15% drop in working days in the office is more than offset by the 50% increase in demand for space per employee.

What is happening, however, is offices are moving from skyscrapers to industrial parks. Another dominant theme of the last 40 years of American cities was the shift of office space into high-rise buildings in city centers. COVID-19 is dramatically reversing this trend as high rises face two massive problems in a post-COVID-19 world.

Just consider mass transit and elevators in a time of mandatory social distancing. How can you get several million workers in and out of major cities like New York, London or Tokyo every day keeping everyone six feet apart? And think of the last elevator you were in. If we strictly enforce six feet of social distancing, the maximum capacity of elevators could fall by 90%, making it impossible for employees working in a skyscraper to expediently reach their desks.

Accustomed to Social Distancing

Of course, if social distancing disappears post-COVID, this may not matter. But given all the uncertainty, my prediction is that when a vaccine eventually comes out in a year or so, society will have become accustomed to social distancing. And given recent nearly missed pandemics like SARS, Ebola, MERS and avian flu, many firms and employees may be preparing for another outbreak and another need for social distancing. So my guess is many firms will be reluctant to return to dense offices.

So what is the solution? Firms may be wise to turn their attention from downtown buildings to industrial park offices, or “campuses” — as high-tech companies in Silicon Valley like to call them. These have the huge benefits of ample parking for all employees and spacious low-rise buildings that are accessible by stairs.

Two types of policies can be explored to address this challenge. First, towns and cities should be flexible on zoning, allowing struggling shopping malls, cinemas, gyms and hotels to be converted into offices. These are almost all low-rise structures with ample parking, perfect for office development.

Second, we need to think more like economists by introducing airline-style pricing for mass transit and elevators. The challenges with social distancing arise during peak capacity, so we need to cut peak loads. For public transportation this means steeply increasing peak-time fares and cutting off-peak fares to encourage riders to spread out through the day.

Making a Smooth Transition

From all my conversations and research, I have three pieces of advice for anyone crafting work-from-home policies.

First, working from home should be part time.

Full-time working from home is problematic for three reasons: It is hard to be creative at a distance, it is hard to be inspired and motivated at home and employee loyalty is strained without social interaction.

My experiment at Ctrip in China followed 250 employees working from home for four days a week for nine months and saw the challenges of isolation and loneliness this created. For the first three months, employees were happy — it was the euphoric honeymoon period. But by the time the experiment had run its full length, two-thirds of the employees requested to return to the office. They needed human company.

Currently, we are in a similar honeymoon phase of full-time working from home. But as with any relationship, things can get rocky, and I see increasing numbers of firms and employees turning against this practice.

So the best advice is to plan to work from home about one to three days a week. It’ll ease the stress of commuting, allow for employees to use their at-home days for quiet, thoughtful work, and let them use their in-office days for meetings and collaborations.

Second, working from home should be optional.

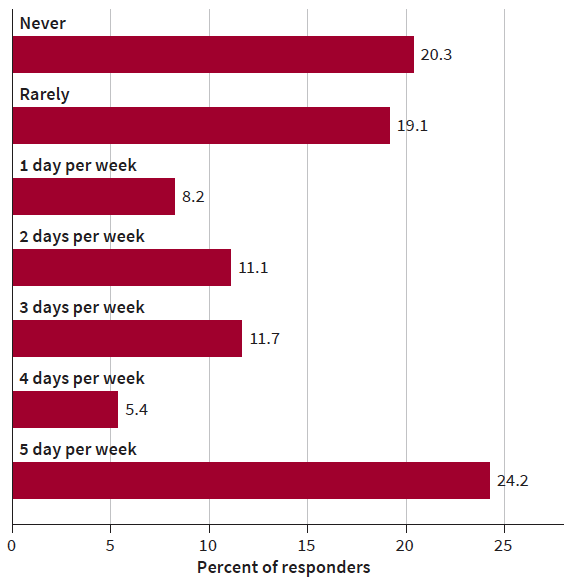

The figure below shows the choice of how many days per week our survey of 2,500 American workers preferred. While the median responder wants to work from home two days a week, there is a striking range of views. A full 20% of workers never want to do it, while another 25% want to do it full time.

The remaining 55% want some mix of office and home time. I saw similarly large variations in views in my China experiment, which often changed over time. Employees would try working from home and then discover after a few months it was too lonely or that they fell victim to one of the three enemies of the practice — the fridge, the bed and the television — and would decide to return to the office.

There Is Wide Variation in Employee Demand for Working From Home Post-COVID-19

Let Employees Choose

So the simple advice is to let employees choose, within limits. Nobody should be forced to work from home full time, and nobody should be forced to work in the office full time. Choice is key — let employees pick their schedules and let them change as their views evolve. The two exceptions are new hires, for whom maybe one or two years full time in the office makes sense, and under-performers, who are the subject of my final tip.

Third, working from home is a privilege, not an entitlement.

For working from home to succeed, it is essential to have an effective performance review system. If you can evaluate employees based on output — what they accomplish — they can easily work from home. If they are effective and productive, great; if not, warn them, and if they continue to underperform, haul them back to the office.

This, of course, requires effective performance management. In firms that do not have effective employee appraisal systems management, I would caution against working from home. The COVID-19 pandemic has challenged and changed our relationships with work and how many of us do our jobs. There’s no real going back, and that means policymakers and business leaders need to plan and prepare so workers and firms are not sidelined by otherwise avoidable problems. With a thoughtful approach to a post-pandemic world, working from home can be a change for good.