Inner-city Cooking Threatens Asia’s Future Forests

An Indian woman cooks food using cow-dung patties and twigs for fuel in New Delhi. New Delhi is now officially the world's most polluted capital, a problem compounded by cooking in the open using solid biomass like cow-dung patties or wood as fuel.

Photo: Money Sharma/AFP/Getty Images

Aerial photos of Asia’s massive urban slums are noteworthy for a distinct lack of greenery in the vast expanse of tin roofs. Yet most slum dwellers still rely on biomass as their primary source of energy for cooking and heating.

While substantial efforts are underway to rapidly deploy clean cooking stoves, the more urgent and “under-our-noses” risk is that as access to wood declines, the urban poor are more likely to buy charcoal when and where they can instead of investing in a stove that they perceive as extravagant and unnecessary.

Improving energy efficiency was a key element of commitments many countries made to reduce carbon dioxide (CO2) emissions in support of the COP21 Paris Agreement. To date, very few are giving any serious attention to the reality that rapid urbanization is likely to drive their most vulnerable people further into energy poverty, as they pay ever-higher prices for the least efficient fuel available.

In the process, we will all pay the cost of losing the valuable ecosystem services that healthy forests provide, including mitigating climate change by serving as carbon sinks.

The charcoal industry warrants immediate, aggressive action.

Urbanization, Energy Poverty and Deforestation

Globally, 32 percent of urban dwellers live in slums; the absolute number of 1 billion is projected to double by 2040, with 38 percent of urban growth being in the slum areas. Sixty percent of the world’s urban slums are in Asia. In South Asia alone, five megacities—Karachi, Mumbai, Delhi, Kolkata and Dhaka—contain about 15,000 distinct slum communities with a total population of more than 20 million. In the past 10 years, China has seen 100 million people migrate from rural to urban areas; by 2020, the number is expected to reach 500 million.

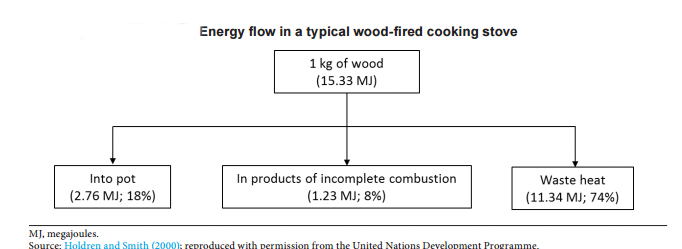

Approximately 3 billion people in the world still rely on biomass for cooking and heating, meaning about 2 million tons (Mt) of it goes up in smoke every day. Those who migrate to urban slums quickly find that collecting wood is no longer an option, and end up spending 20 percent (or more) of their meager incomes on this basic energy need. The value derived from wood as an energy source is remarkably low: on a typical three-stone fire pit, only 18 percent of energy available in the wood makes its way into the cooking pot.

A large part of charcoal’s appeal is that it weighs a fraction of a similar volume of wood and is easy to break into small pieces, making transport and use much easier.

Traditional charcoal production processes, which involve a slow wood burn, effectively remove water and impurities. The downside is that a mere 20 percent of the wood’s original energy remains in the end product. Additionally, most stoves designed for charcoal have efficiency rates of 20 percent to 30 percent. In effect, production and use of charcoal leave an overall efficiency of just 4 percent; some 96 percent of the initial wood energy is lost.

Put another way, for every 100 trees harvested, end-users in the city are able to access the energy content of just four. Globally, demand for biomass is expected to triple in the next 30 years. Urbanization is likely to push up charcoal’s share.

Other Issues Along the Charcoal Supply Chain

At present, some 90 percent of wood consumed is used for fuel wood and charcoal production. In 2012, official charcoal production of 30.6 Mt was worth approximately $9.2 to $24.5 billion annually. Yet these figures likely grossly underestimate reality.

In many places, charcoal production and trade is largely an informal industry, with poor and landless people in rural, unprotected forested areas producing small volumes, which they sell to local markets or to intermediaries. Some Asian countries (Bhutan, India, Indonesia, Philippines and Thailand) have scaled up production to commercial scales, with wood being supplied through commercial trade. In either case, getting the charcoal to end-users may be a complex system, involving a large number of actors, each of which adds a profit margin ultimately driving up the end price.

While supply and demand for charcoal is largely a local concern, the associated deforestation has negative global consequences for the climate, biodiversity, rainfall patterns and the livelihoods of local populations, among others. The World Wildlife Fund estimates that up to 420 million acres of forest could be lost between 2010 and 2030—equivalent to the landmass of Germany, France, Spain and Portugal combined. Use of wood for cooking or industry is one element, along with deforestation for agriculture, mining, etc., that will rob the world of large sinks for CO2, and further accelerate global climate change.

Time for Strategic Action

To end energy poverty and reduce climate change impacts, governments must act quickly to regulate charcoal production and trade as an intermediate step toward accelerating the deployment of cleaner cooking fuels and clean, improved cook stoves.

Effective action will require parallel effort across three areas:

Technical solutions to improve methods to produce, supply and use charcoal and to develop and deploy improved and clean cook stoves, as well as alternative fuels.

Policy solutions to impose norms (minimum efficiencies, etc.) and controls on charcoal producers and on cooking stoves (minimum efficiencies, exhaust of the smoke, ventilation, etc.).

Market solutions to support deployment of proven technology solutions, such as building markets, scaling production (manufacturing, distribution, etc.), financing for enterprises and establishing micro-credit for households.

Together, such actions could deliver multiple benefits to households, to countries and to the world:

- At the household level, reduce energy costs of poor households, improve the health and well-being of occupants (particularly women and children), and allow for other economic activity or education.

- At the national level, reduced demand for fuelwood, charcoal and primary wood for charcoal production can reduce the rate of deforestation, lower the incidence of illegal production and trade, and deliver additional revenues through more effectively regulated energy supply.

- At the world level, reduced deforestation due to more efficient charcoal production and reduced fuelwood and charcoal consumption will increase the global area of forest available for contributing to achieving the goals of the COP21.