Paris Climate Agreement and Making Sure Climate Finance Reaches the Poorest

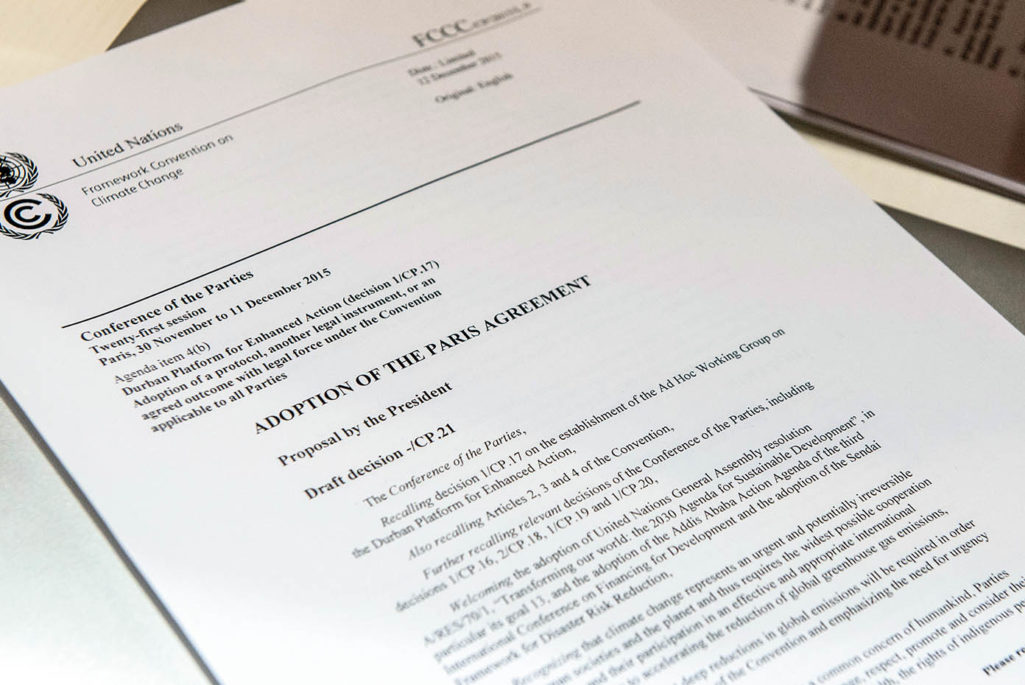

A copy of 'The adoption of the Paris agreement' is pictured after the announcement of the final draft by French Foreign Affairs minister Laurent Fabius at the COP21 Climate Conference in Le Bourget, north of Paris, on December 12, 2015.

Photo: Miguel Medina/AFP/Getty Images

The recent Paris climate agreement universally signed by more than 190 countries was generally tougher in signaling the end of fossil fuels than many had expected:

- The agreement signals a commitment “to reach global peaking of greenhouse gas emissions as soon as possible” and “balance” emissions with sinks (systems for storing carbon) by the second half of this century. This can be interpreted to mean that global emissions of greenhouse gases will need to peak within a generation.

- The agreement also limited temperature increase to 2 degrees above pre-industrial levels, but would “pursue efforts” to limit that increase to 1.5 degrees. This latter target is considered vital to safeguard some of the most vulnerable nations; most negotiators had not expected this target would be included in the final agreement.

- Despite the emission reduction commitments of almost 190 countries, estimates still point to a warming of more than 2.7 degrees. To try and mitigate this shortfall of hitting the 2 degree temperature target, the agreement includes provisions that require all countries to revisit their emission plans every five years. These will then be assessed before that five-year commitment is finalized. This five-year revision mechanism and public review will allow countries to become more ambitious in terms of reducing greenhouse gases over time as technologies develop.

Far-Reaching Commitments on Climate Finance

The agreement also makes far-reaching commitments on climate finance:

- It commits developed countries to “take the lead in mobilizing climate finance from a wide variety of sources.” This finance “should represent a progression beyond previous efforts” so there is a guarantee that finance will increase over time.

- The agreement also says, “other parties are encouraged to provide or continue to provide such resources voluntarily.” These other parties include countries such as China that are already providing significant sums of international climate finance but do not want it counted in the same way as developed country finance.

The poorest countries have very low emission levels, but have huge needs to adapt to climate vulnerability.

Making Sure Finance Reaches Poor Countries

While much attention has been focused on climate finance and the symbolic number of $100 billion per year, it is also important to make sure that this money reaches poor countries.

The poorest least developed countries have very low emission levels, but have huge needs to adapt to climate vulnerability. These nations have also outlined how they plan to contribute to post-2020 global climate action through ambitious climate action plans also known as intended nationally determined contributions (INDCs). To implement the action plans, these poor countries will need around $93.7 billion each year, according to a recent IIED estimate.

If all the climate finance goes to renewable power projects in China and other emerging economies, this will not help the poorest countries to transition to low carbon resilient pathways.

Importantly, the agreement also states that finance should “aim to achieve a balance between adaptation and mitigation” and take account of “the priorities and needs of developing country parties, especially those that are particularly vulnerable to the adverse effects of climate change and have significant capacity constraints, such as the least developed countries and small island developing States.”

Finally, the agreement acknowledges that while private sector finance is more likely to flow to mitigation (for example, through energy and transport investments), it is important to consider “the need for public and grant-based resources for adaptation.”

Making Sure Climate Finance Reaches Poor People

Once climate finance gets down to the country level, it is vital to make sure it reaches poor people. Strikingly, poor people are already expending their own limited resources to adapt to climate change. This includes risk-reduction investments, post-disaster spending, investment in temporary or permanent migration from areas hit by climate variability and climate change and expenditures on products and technologies that help households adapt and respond to climate change. International finance needs to complete this spending by poor people themselves.

Another channel for finance is for low-income groups to be mobilized and organized to manage development finance and now climate finance themselves. Support is now needed to facilitate these low-income groups to deliver climate finance directly to poor households.

Social protection is one of the largest public policy responses aimed at poverty eradication. It has evolved from a focus on safety nets to include both short-term interventions to reduce the impacts of shocks and longer-term mechanisms that impact chronic poverty. Social protection can be redesigned to be climate-resilient and avoid promoting maladaptation. Already many of Bangladesh’s and Ethiopia’s social protection schemes support climate-vulnerable households, while India’s Rural Employment Guarantee Scheme provides jobs to clean up ecosystems and invest in climate-resilient infrastructure. The social protection schemes provide an innovative delivery channel for the flow of climate finance.

Local governments are at the forefront of interacting with citizens, providing local level infrastructure such as roads and managing local natural resources. So local government is key to supporting poor households to adapt to climate change. Natural resources such as water are coming under pressure from climate change and local governments can play a key role in managing conflict and sustainable use. Local governments also can provide seed funds for local level energy infrastructure such as off-grid hydro and solar technology. So channelling climate finance through local government can provide an effective way to help poor households adapt and mitigate climate change.

National Development Banks are government-backed financial institutions that have a specific public policy mandate to provide long-term financing to risky sectors that remain uncatered to by commercial banks. They are increasingly being used to channel climate finance. For instance, the National Bank for Agriculture and Rural Development is the accredited national implementing entity under the Adaptation Fund in India. The Development Bank of Rwanda is responsible for channeling climate finance to private sector investors in Rwanda and Bangladesh’s Central Bank is catalyzing financial institutions to provide green lending to the private sector. However, the focus areas, capacities, instruments and structures of national development banks differ, particularly in new areas of climate finance.

Harnessing innovative private sector support: Countries have begun investing through innovative instruments targeting climate and energy financed on the most poor. Special purpose agencies have been set up by some countries to ensure finance builds resilience of the most poor. The Infrastructure Development Company Limited (IDCOL) in Bangladesh is one such example of a financial entity that has succeeded in providing 2.5 million Solar Home Systems (SHS) in Bangladesh. Although initially criticized for excluding the poorest, the changes in IDCOL policies—offering low-interest loans and smaller cost-effective SHS products—have helped distribute small SHS to around 83 percent of people living below the poverty line in the sample study area.