Should AI be Treated the Same as Humans Legally?

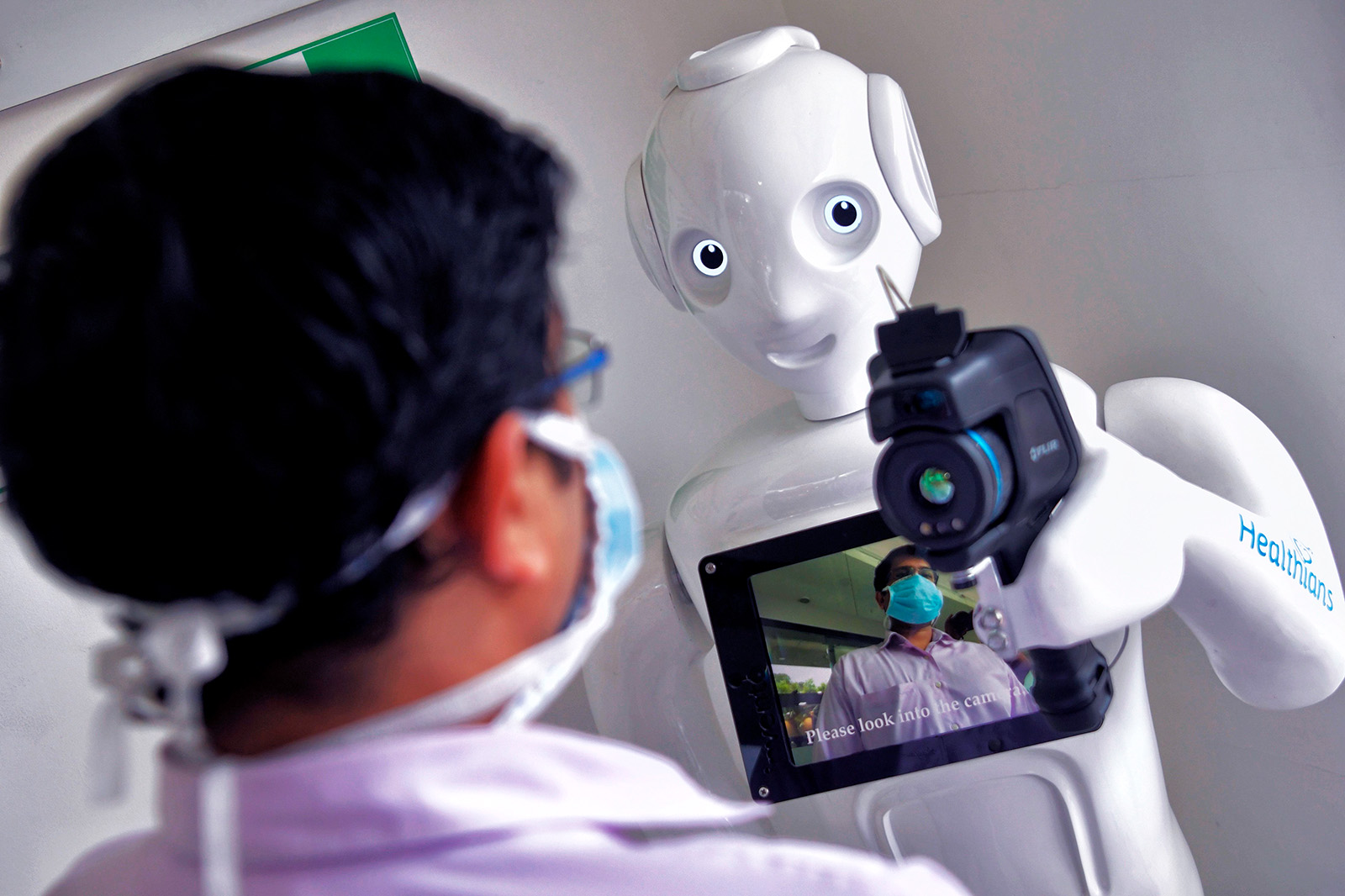

A hospital worker stands in front of a robot equipped with a thermal camera installed to conduct preliminary screenings to help prevent the spread of COVID-19. Currently, different legal standards apply to humans and AI that perform the same tasks.

Photo: Manjunath Kiran/AFP via Getty Images

Artificial intelligence and humans are increasingly performing the same tasks, yet their behavior is treated very differently under the law.

Ryan Abbott is the professor of Law and Health Sciences at the University of Surrey School of Law in the United Kingdom, and author of The Reasonable Robot. Abbott argues that holding AI and humans to similar standards in areas such as tax policy, accident law and intellectual property would help us better prepare for a future that is becoming increasingly automated.

ABBOTT: AI is automating more and more human activities, like working as a cashier, manufacturing vehicles and making new songs or music. Yet when you have a machine, and a person doing the same sorts of things, different legal rules currently apply.

The Law is Discriminating

This creates a system where the law is essentially discriminating between either AI or human behavior in one way or another, without necessarily having intended to. My book argues that it would be socially advantageous to regulate human and AI behavior more neutrally.

That isn’t to say that an AI machine would have rights, and it certainly isn’t morally entitled to rights. AI behaves like a person, but it is not like a person.

BRINK: So how would this play out in practice? What might be the implications for someone who is running a company with an AI component?

ABBOTT: Let me give you an example that will make it more concrete. For several decades, AI has been generating new creative works, like articles and songs, without necessarily having a person involved who traditionally qualifies as an author.

But in the U.S., a human author is needed for copyrights to exist. If a person writes an article, they get copyright protection — copyright is the primary legal framework by which we encourage people to generate creative writings.

But what if you use a machine to generate an article that has commercial value, like what the Washington Post does with HelioGraf? In the United States, because you don’t have a human author, the article gets no protection. So, your competitors may be able to simply copy and reuse that article, without crediting you.

We need copyright protection because we think that, without it, there won’t be adequate incentives for people to be creative. In the case of an AI-generated work, you wouldn’t have the machine owning the copyright because it doesn’t have legal status and it wouldn’t know or care what to do with property. Instead, you would have the person who owns the machine own any related copyright. That would encourage the development of machines that can produce commercially valuable creative output and ultimately result in more creative output for society at large.

The U.S. has a corporate work-for-hire doctrine, under which an artificial person in the form of a corporation can be deemed an author. That’s the case for works generated within the scope of employment even though, obviously, the corporation itself didn’t literally write anything. I’m arguing in favor of a similar sort of regime where the machine’s owner would be entitled to copyright in an article, by virtue of ownership of the machine.

Filing Patents for Robots

To bring this to life, I assembled and worked with a team of international patent attorneys and together we filed the world’s first legal test case for two inventions made autonomously by AI without a traditional human inventor.

These two inventions have already been found, essentially, to be patentable by the U.K. and European Patent Offices, but the offices are now objecting to them on the basis that they don’t disclose a traditional human inventor.

We listed AI as the inventor on these applications, again not to give it credit or rights, but to inform the public how the invention was generated and to keep people from claiming credit for work done by machines. Because if I had an AI machine that makes music, and it makes a hundred thousand songs for which I claimed to be the writer, it would change what it means to be a human artist, and it would devalue human creativity.

Labor and Robots are Not Taxed Equally

BRINK: One of the most striking aspects of this issue is how it impacts taxation.

ABBOTT: There is a need for more neutral treatment of taxes between AI and people. For example, if you have a robot working in McDonald’s as a cashier, replacing a human being, tax policies currently encourage McDonald’s to automate. That’s the case for several reasons, but the most obvious is that McDonald’s doesn’t have to pay payroll taxes on the AI, but they do on a person. Or in the U.K., they’d have to make national insurance contributions.

In some areas of the law, we are preventing machines from doing a better job than people, but in other areas, we are preventing people from doing a better job than machines.

You can also more favorably accelerate deductions from any types of AI, and there’s indirect tax benefits to automating. So, our current tax policies encourage businesses to automate even when it isn’t otherwise efficient.

That’s a problem. The even bigger problem may be that automation can dramatically reduce tax revenue. That’s because 90% of the U.S. federal government’s revenue comes from payroll and income taxes. A relatively small amount, less than 10%, comes from company taxes.

Rebalancing the Tax Equation

When McDonald’s automates, we will lose the payroll taxes on the person, their income taxes, and even if McDonald’s becomes a little more profitable, a relatively small amount of that is remitted in taxes.

I’m not suggesting that we literally tax robots because it would be very difficult and counterproductive. What I’m suggesting is that we decrease the extent to which we’re taxing human labor, and tax capital more than we do currently.

Right now, most of our taxes target labor in large part because we think capital is mobile, and it will leave jurisdictions where we tax it, but in reality there’s a lot of reasons for people to invest in the United States. Having a system that is more balanced between how we tax workers and businesses would promote economic efficiency and also promote a fairer distribution of wealth.

The Problem with Tort Law

BRINK: The third area is where there’s a discrimination is tort law, but this time it is discriminating against the AI as opposed to against humans.

ABBOTT: In some areas of the law, we are preventing machines from doing a better job than people. In other areas, we are preventing people from doing a better job than machines.

With tort liability, when a person causes an accident, we ask whether a reasonable person would have caused that accident. That’s our basic negligence standard. If a kid jumps in front of your car and a reasonable driver couldn’t have stopped, you wouldn’t be liable for causing an accident. If we think that a reasonable person would’ve slammed on the brakes faster and avoided a collision, then you would be liable.

Yet because machines are commercial products, they are generally evaluated under product liability law, which has a higher “strict” standard for liability.

That means that, even if you have a machine that tends to be safer than a human driver, we are subjecting it to heightened liability standards which results in greater cost. And that’s not good if we want to encourage people to adopt safer technologies.

BRINK: So would the liability flow to the owner of the car, or the manufacturer of the AI in the car?

ABBOTT: The best party for liability remains the manufacturer of the car, rather than its owner. Because that’s something they can insure against. Also, they are in the best position to improve the car’s safety.

Using Humans for Certain Tasks

Not only are driverless cars going to be safer than people, they are almost certain to be much safer than people, potentially to the point where they almost never cause accidents.

BRINK: At that stage we’re holding humans to AI standards, rather than the other way around.

Exactly. A better standard might be to say to a person: You’re allowed to drive, but if you cause an accident that a self-driving car would not have caused, you’re going to be liable for it. Just as we’re holding machines to human standards when people are the standard way things are done, we may have to hold people to a machine standard once machines are the standard way things are done. That’s not just in driving, but in everything, like practicing medicine or law.

If a surgical robot could remove a human cancer twice as effectively as a human doctor and in half the time with fewer complications, it would be concerning to let people continue to competitively practice surgery. More than financial liability, for physicians who swear to do no harm, that sort of activity may even be unethical.

Right now, we’re setting the bar for machines at the level of human activity, because that’s what we want them to improve on. But once they get over that bar, you’re not going to want to have a person doing the job an AI machine could do better in a number of areas.

That isn’t to say that people won’t want to do those activities for fun or personal satisfaction. But they won’t be needed to do it for work.