South Korea Once Recycled 2% of Its Food Waste. Now It Recycles 95%.

A man walks past separated dustbin for the recycling of waste materials at a rest stop of an expressway in southern Seoul.

Photo: Jung Yeon-Je/AFP/Getty Images

The world wastes more than 1.3 billion tons of food each year. The planet’s 1 billion hungry people could be fed on less than a quarter of the food wasted in the U.S. and Europe.

In a recent report, the World Economic Forum identified cutting food waste by up to 20 million tons as one of 12 measures that could help transform global food systems by 2030. And South Korea stands out — taking the lead by recycling 95% of its food waste.

But it wasn’t always this way.

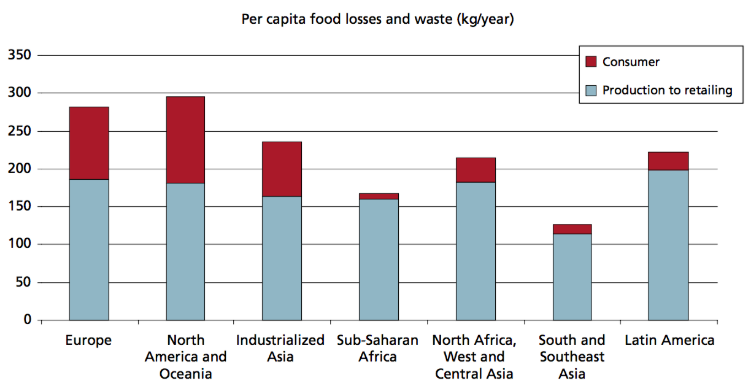

The mouth-watering array of side dishes that accompany a traditional South Korean meal — called “banchan” — are often left unfinished, contributing to one of the world’s highest rates of food waste. South Koreans each generate more than 130 kg of food waste each year. By comparison, per capita food waste in Europe and North America is 95 to 115 kg a year, according to the Food and Agricultural Organization of the United Nations.

But the South Korean government has taken radical action to ensure that the mountain of wasted food was recycled.

What Changed?

As far back as 2005, dumping food in landfills was banned, and in 2013 the government introduced compulsory food waste recycling using special biodegradable bags. An average four-person family pays $6 a month for the bags, a fee that helps encourage home composting. The bag charges also meet 60% of the cost of running the scheme, which has increased the amount of food waste recycled from 2% in 1995 to 95% today. The government has approved the use of recycled food waste as fertilizer, although some becomes animal feed.

Technology has also played a leading part in the success of the scheme. In the country’s capital, Seoul, 6,000 automated bins equipped with scales and radio frequency identification weigh food waste as it is deposited and charge residents using an ID card. The pay-as-you-recycle machines have reduced food waste in the city by 47,000 tons in six years, according to city officials.

Residents are urged to reduce the weight of the waste they deposit by removing moisture first. Not only does this cut the charges they pay — food waste is around 80% moisture — but it also saved the city $8.4 million in collection charges over the same period.

Waste collected using the biodegradable bag scheme is squeezed at the processing plant to remove moisture, which is used to create biogas and bio oil. Dry waste is turned into fertilizer that is, in turn, helping to drive the country’s burgeoning urban farm movement.

Urban Farms

The number of urban farms or community gardens in Seoul has increased sixfold in the past seven years. They now total 170 hectares — roughly the size of 240 football fields. Most are sandwiched between apartment blocks or on top of schools and municipal buildings. One is even located in the basement of an apartment block. It is used to grow mushrooms.

The city government provides between 80% and 100% of the start-up costs. As well as providing food, proponents of the scheme say urban farms bring people together as a community in areas where residents are often isolated from one another. The city authorities are planning to install food waste composters to support urban farms.

Which brings us back to banchan. In the long term, some people argue South Koreans will need to change their eating habits if they are really going to make a dent in their food waste.

Kim Mi-hwa, chair of the Korea Zero Waste Movement Network, told Huffington Post: “There’s a limit to how much food waste fertilizer can actually be used. This means there has to be a change in our dining habits, such as shifting to a one-plate culinary culture like other countries, or at least reducing the amount of banchan that we lay out.”

This piece previously appeared on the World Economic Forum.