The Bigger Risks to Business

A general view of the BHS store on Commercial Street in Newport, Wales. The store is one of 20 stores across the UK that closed. The collapse of BHS put 11,000 UK jobs at risk and left a £571m pension deficit.

Photo: Matthew Horwood/Getty Images

Familiar risks top the agendas of most business leaders. CEOs are preparing for slow economic growth caused by demographic trends, political instability, and the unwinding of unprecedented monetary stimulus. They must respond to the blistering pace of technological change in a way that makes them the disrupters, rather than the disrupted. Additionally, they face talent challenges as the millennial generation gravitates toward technology companies, startups, or nonprofits.

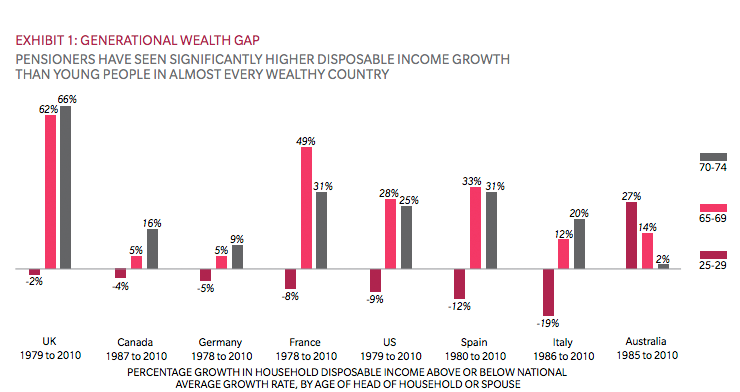

These immediate risks demand attention. Yet, important social trends are also creating structural risks that must be understood and considered in strategic planning: widening gaps in wealth, generational inequality, and shortfalls in retirement funding.

Media outlets warn of alienated populations and the potential consequences, but this has not been a focus for executive suites and boardrooms. That is a mistake. These trends may give rise to global crises that could present much graver threats to business returns than the familiar challenges that most companies grapple with every day.

Revolution in Work

Recent soundings in the United States and United Kingdom show that about half of all voters are hostile to international trade and globalization. Many feel that foreigners are stealing their jobs, both as immigrants and by way of “offshoring.” Yet the frustrations associated with globalization—erroneously, for the most part—may turn out to be minor compared to those caused by the coming revolution in work.

Advances in artificial intelligence and robotics promise to shunt humans out of many jobs, and to profoundly change the kinds of jobs that generate decent incomes. Nearly every company we work with understands that technological advances will allow them to operate with fewer employees, of whom many will need new skills.

The transition to this new world of work will see enormous gains for those with the skills increasingly demanded. But for many, the transition will be painful. It will prematurely end the working lives of those viewed as too old to retrain and impose large adjustment costs on many younger workers. Unemployment is likely to be high until workers made redundant by technology can find new uses for their labor. This revolution in work may create problems of income inequality that dwarf the current challenges.

Intergenerational Inequalities

This will come on top of already emerging intergenerational inequalities in wealth. (See Exhibit 1.) Those entering the workforce today carry more student debt and, in most cities, face higher real housing costs than their parents did—which is why so many do not leave home until almost age 30. Those with parents wealthy enough to pay their university fees and help them buy a home will prosper. Many of the rest will struggle to get ahead and improve on their parents’ standards of living.

Retirement Funding Shortfall

Making matters worse, funds from corporations and governments for future retirements are likely to prove inadequate. With birth rates declining and longevity increasing, each retiree will need to be supported by a diminishing number of workers. According to a UN study, by 2035 the ratio of retirees (those 65 years-old and older) to working-age people will have doubled since 1975.

Such dramatic shifts in the economic fortunes of various groups and the widespread disappointment of expectations are sure to have serious consequences for businesses, not only directly, but also through social and political action.

For example, the looming unemployment risk could encourage politicians and unions to compel firms to limit redundancies in industries being transformed by laborsaving technology. Since this would make production more expensive in countries with such limitations, it would also lead to calls for restrictions on imports from countries that did not impose such limitations on the use of laborsaving technology.

Historically, technological advances that destroy particular jobs, from the mechanical loom to the desktop computer, have not caused long-term unemployment. Labor has quickly been redeployed elsewhere, often to produce what were considered luxuries before new technology increased aggregate output or to supply goods and services not previously imagined (consider the growing number of masseurs and yoga instructors).

Widespread Unemployment

Many commentators familiar with this history nevertheless claim “this time is different,” and that we run the risk of persistent widespread unemployment. These fears will only mount as new technology begins to eliminate jobs in sectors that now employ millions of people—as driverless cars may soon do in the case of taxi, bus, and truck driving.

We can already see glimpses of the way businesses will be affected by skepticism about the capacity of the economy to find new uses for labor. In September, General Motors had to agree to rebuild an assembly line for cars and trucks at a plant in Ontario after Canadian workers threatened to strike. As the “price” for closing one of two assembly lines at its largest plant in Canada, GM moved production of one engine to Ontario from Mexico.

Retraining

Business leaders need to honestly assess how many of their employees will not be gainfully employed in five to 10 years. If they cannot be laid off, they will need to be retrained to do something valuable—a contingency for which firms should have plans.

Governments must also plan for the coming changes, adapting education to the new demands of high-tech economies. But the more rapidly the changes occur, the greater the need for retraining the adult workforce and the greater the role of businesses. Some countries and businesses are already responding. For example, both Singapore and JPMorgan Chase have considered and invested in a number of experimental programs to help people acquire the skills required for decent jobs in the future, preparing them to work in professions experiencing shortages and to obtain skills likely to be in high demand in a digital future.

New outlooks on life may be as important as new skills. Many people gauge progress by their children’s monetary incomes, expecting them to surpass their own. With many of the new digital products becoming so cheap, such as access to almost all of human knowledge via the Internet, monetary income is an increasingly incomplete way of measuring well-being. A more sustainable measure could include some combination of wealth, happiness, leisure, and the state of the environment, for example.

My prognosis may seem gloomy, but only because I have so far ignored the extraordinary growth in problem-solving innovation—itself aided by the technological trends at issue. Consider how well prepared companies and governments have become for complex risks that once seemed similarly insurmountable, such as terrorist attacks, viral outbreaks and volatile energy prices. The Energy Information Administration forecasts that solar and wind power will overtake coal-fired generation in the United States by 2029. Bloomberg Energy estimates that by 2040 electric vehicles may account for one-third of all new vehicle sales globally, having become no more expensive that conventional cars. Only a few years ago, a scenario such as this would have been inconceivable.

What’s needed now is leadership and a sense of urgency about addressing inequality, generational conflict, and obvious retirement funding gaps. It is true that the timing and magnitude of these strategic risks for corporations is uncertain. But unless company leaders plan now, rather than wait for government fixes, they will not be among the winners in the future.

This article is from the sixth edition of the Oliver Wyman Risk Journal.