The Global Internet Is Fracturing

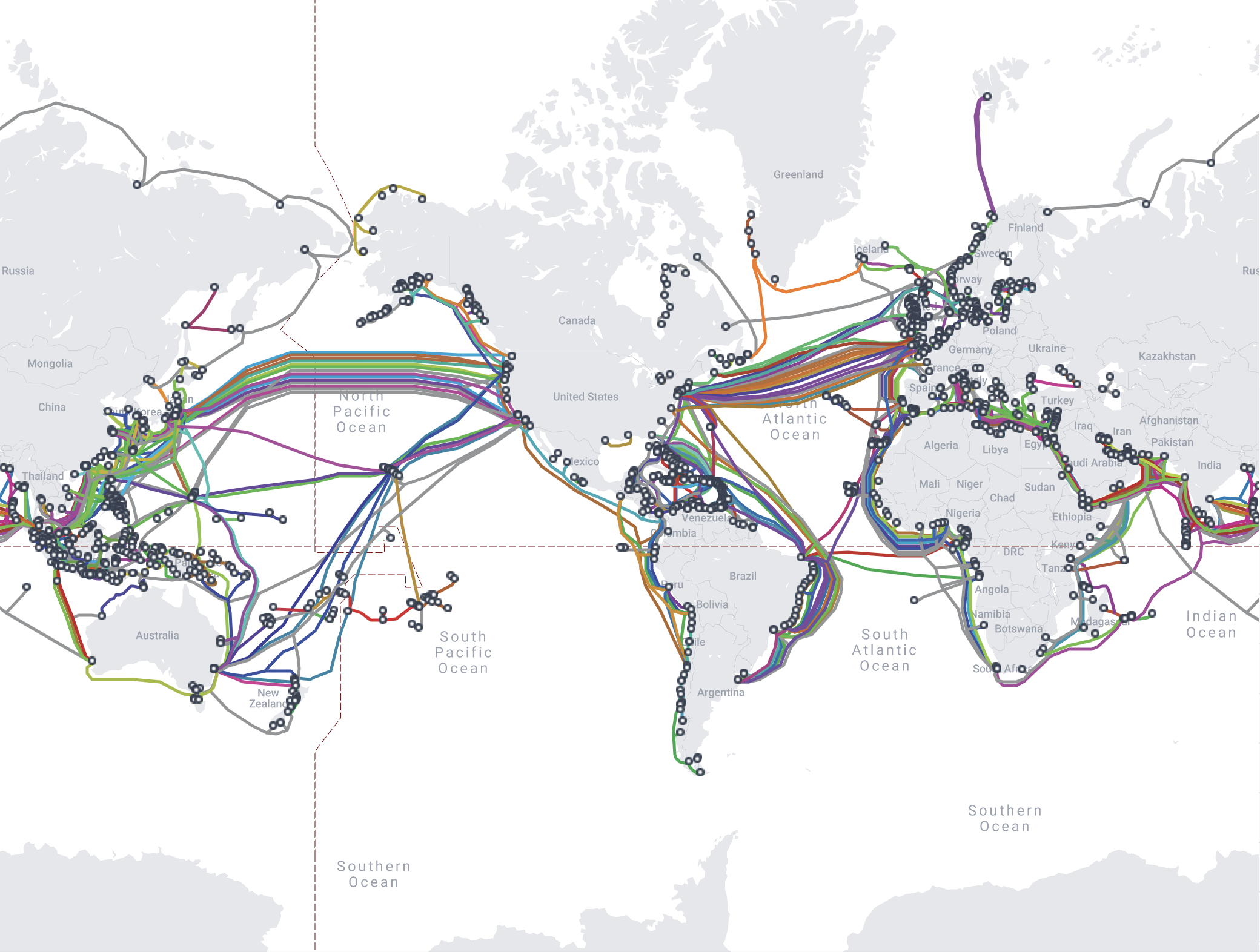

The underlying backbone of this is the global network of undersea fiber optic cables.

Source: Getty Images

The concept of a single global internet is breaking down. At the digital level, this is because of efforts by countries like China and Russia to build national firewalls. But there is also a major change happening to the internet’s physical backbone, particularly the fiber optic cables that cross international borders.

BRINK sat down with Steve Song, policy adviser with the Mozilla Corporation, for his perspective on how the internet — and its power dynamics — are changing.

SONG: The popular notion of a splintered or balkanized internet first emerged with China’s attempts to control information flows in and out of its country and the creation of the Great Firewall of China. That was followed by other countries determined to be able to operate the internet independently of the rest of the world, where we have seen a rise in internet shutdowns and social media shutdowns.

This is surprisingly easy for governments to do because every telecommunications operator is dependent on a license issued by the country they offer services in to continue business. The risk of not complying with a request from a government to stop the internet flow puts their entire country’s operation at risk. Internet shutdowns are very, very tricky to deal with.

The internet is composed of layers. And the layers that we’re talking about in terms of the Great Firewall are at the digital level. But below the digital level is the infrastructure layer of the internet — the physical cables and wireless technologies that carry internet traffic. The underlying backbone of this is the global network of undersea fiber optic cables.

Power Is Shifting On the Sea Bed

Historically, these cables have been owned by telecommunications companies or consortia of telecommunications companies, which has enabled the international growth of the internet in quite a spectacular way.

What’s changing now is that Silicon Valley giants have become such large consumers and movers of data, especially between and among their data centers, that they’ve begun to invest in their own undersea cables.

And that’s bringing about a real shift in power, in terms of global internet infrastructure, because the Silicon Valley giants like Facebook, Google, Microsoft, Amazon and others have comparatively much larger amounts of money to invest compared to traditional telecommunications companies. They can afford to invest in undersea cables at a level that significantly eclipses the resources of telecommunications companies.

At the same time, you’ve also got undersea fiber optic infrastructure being financed/built by national governments like China that is intended to facilitate its political and economic ambitions, in terms of cementing its connections with other countries around the world.

That affects everything, especially in cybersecurity. Geopolitics is increasingly a factor for countries making strategic choices about which cables should land on their shores. Governments may be more comfortable and confident in infrastructure that they or their allies own or operate, versus infrastructure operated by political or economic competitors.

A Concentration of Power in the Hands of a Few

BRINK: What are the implications of all this?

SONG: The effects, at least initially, are likely to be subtle. If you think about trade in the 16th, 17th century with sailing ships, the direction of trade was affected by the wind and the continental currents. Currents influenced the way that trade evolved. And similar things are happening with the internet’s physical infrastructure: If there’s a shorter path with faster response times from one particular piece of infrastructure, there’s going to be a bias toward using it.

Ultimately, technology is a magnifier. It can magnify economic growth, but it can also magnify inequality. We are seeing the results of that with the concentration of internet economic power in Silicon Valley. Having a company like Google own the undersea cable and own the higher-level digital infrastructure that services companies creates a level of vertical integration, which is going to make it very difficult to sort out whether internet infrastructure is enabling a level playing field.

Falling Outside Internet Governance

BRINK: Are they just as accountable as telcos to the internet’s international bodies and international law, or do they have a different standing?

SONG: That is a very interesting question, if Google, for instance, has a connection from its data center in California over its own undersea cable to its data center in Johannesburg, the data moving between those centers may not be traveling over the internet at all. That means it falls outside of the realm of conventional governance mechanisms in some ways.

Certainly institutions like ICANN and the ITU are aware of this. But from a jurisdiction perspective, it’s not clear that either institution has an appropriate mechanism or mandate to deal with it.

I think the most significant opportunity for regulation is actually at the landing points for undersea cables. For any country, if a Facebook or Google seeks to land an undersea cable, then setting the terms on which that cable is allowed to land I think is the biggest opportunity for regulation and for intervention and ensuring fair play. Governments need to ensure that new undersea capacity is going to amplify equitable digital development in their country; that the benefits flow equally in both directions.

BRINK: What is the risk from this to a company that operates internationally?

SONG: Significant concentration of power in digital services makes it difficult for new competition to emerge. If a company was attempting to launch a service in competition with Google, for example, the combination of their ownership of both global infrastructure and services may give them an unbeatable edge.

One of the keys to addressing this potential risk is to ensure that cables that are permitted to land, do so on terms that guarantee “open access,” the principle that any licensed terrestrial operator may purchase capacity and on equal terms.