The Global Potential of Growth Economies: Coming Opportunities and Challenges

This aerial picture shows a general view of the skyline and the Chao Phraya river passing through Bangkok. With an ever-larger and increasingly educated middle class, particularly in Asia and Latin America, growth in consumption and business investment in these regions will not only lead the way as the engines of global economic activity but will contribute to a gradual transition toward higher-end consumer goods and business services.

Photo: Christophe Archambault/AFP/Getty Images

Although the economic story of the 21st century is still very young, its first two decades can arguably be summarized as a period of transition in global economic leadership. The North Atlantic-centric economies (those in North America and Western Europe) that have dominated the global economic landscape for the better part of the past century and a half are being surpassed by the faster-growing economies of Asia, Latin America and Africa.

The transition will likely be complete by the end of 2030, with the anchors of global economic growth cast across the Pacific and the Southern Hemisphere.

With an ever-larger and increasingly educated middle class, particularly in Asia and Latin America, growth in consumption and business investment in these regions will not only lead the way as the engines of global economic activity, but they will contribute to a gradual transition toward higher-end consumer goods and business services, such as health care, insurance and investments.

Transition in Global Economic Leadership

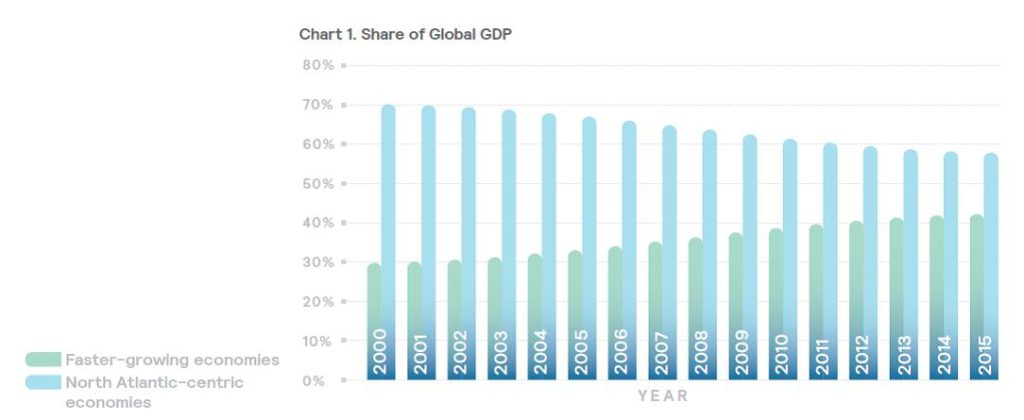

Since 2008 and the peak of the financial crisis, faster-growing economies* have dominated new economic activities globally. According to estimates from the World Bank, the global economy has added $10.655 trillion to its GDP during this period, roughly $8.28 trillion of which—or more than 77 percent—has come from the faster-growing economies. Since the beginning of the century, nearly 65 percent of all new activity has occurred in these economies, which, as of the end of 2015, represent slightly more than 42 percent of the global economy, up from almost 30 percent at the end of 2000 (see Chart 1).

Economic recoveries post financial crisis have, in general, proved to be weaker than other recoveries, impacting investments, employment and regulatory environments disproportionately. However, the outperformance of faster-growth economies over the North Atlantic-centric ones (where the financial crisis originated) since 2008 has been largely due to significantly stronger fiscal balances, favorable demographics and a growing and consuming middle class that is increasingly confident about its future income prospects. Relatively stronger fiscal balances have permitted continued government investment in national and regional housing and transportation infrastructures (especially across Asia, Latin America and the Persian Gulf), contributing to the fast rate of urbanization. Investment in health care and educational infrastructures has continued to increase longevity, contributed toward productivity growth, and improved the relative competitiveness of agriculture, manufacturing and even certain services sectors.

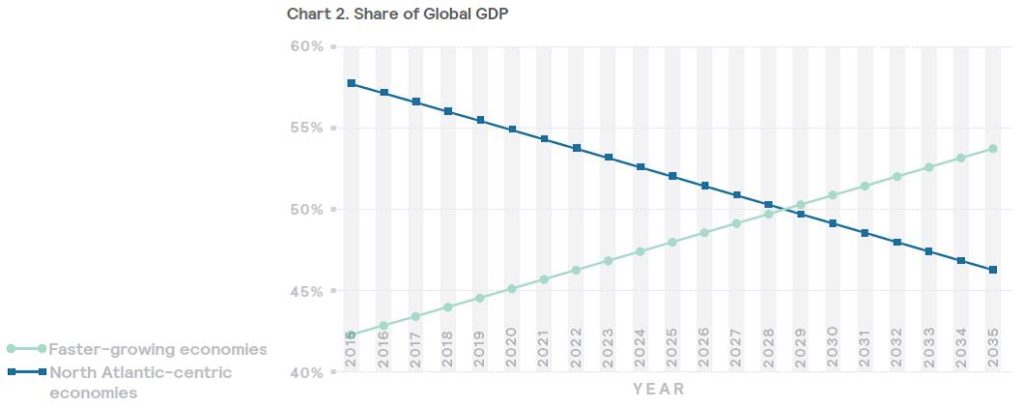

Faster-growing economies are likely to see a slight downtick from their 2000–2015 average as Chinese growth converges to more sustainable levels. But with an average growth of 4.0 percent, we expect the faster-growing economies will surpass their North Atlantic-centric peers and complete the transition to global leadership by 2030 (Chart 2).

The Rising Middle Class

The North Atlantic-centric economies have benefited greatly from their consumers’ size and growth over the past half century. As the transition in global leadership progresses over the coming decades, the faster-growing economies of Asia and Latin America, in particular, will begin to experience this stabilizing economic force as their investment in the infrastructure of consumption begins to pay off.

By 2025, 10 of the top 25 cities ranked by GDP will be located in the faster-growing economies. When measured by the number of individuals making more than $20,000 per year (a figure that could be considered upper middle class even by the higher-cost standards of larger cities by 2025), 14 of the top 25 will likely be cities located in faster-growing economies.

The historical experiences of the North Atlantic-centric economies teach us that, as urbanization evolves and the middle class begins to dominate the landscape of cities and economic activity, growth in demand for services such as health care, education, leisure and finance (that is, insurance and investments) accelerates. But the middle class of Asia, Latin America, the Middle East, Africa and even Eastern Europe will be a different middle class than in the North Atlantic. Cultural, educational, and religious traditions and qualities will need to play a significant role in “new” offerings, particularly in services.

Success for many multinationals in this arena may very well be defined in terms of “innovation differentiation.” Chief among these differentiating factors are:

Investment, financial services and insurance for retirement. Retirees and savers in these countries will play a significant role in the transfer of capital to companies (as they have done in the advanced economies), but meeting their needs will require different innovations and product offerings. To be successful, companies will need to cater to the specific needs of the market instead of relying on the models of advanced economies.

Transition to a service economy. Although much of the infrastructure of the growing economies will still be pivoting off of their competitive advantage in manufacturing and agriculture over the coming years, a larger, better-educated and wealthier middle class will demand more and more services. Human capital plans designed around meeting the labor market needs of just agriculture and manufacturing will thus be grossly inadequate. The new competitive advantage will be a workforce that is prepared for this transition to services.

The enhanced role of technology. Technology is not all about robotics and the assembly line replacing humans. Over the past three decades, technology has contributed to significant productivity gains in growth economies in the agricultural and manufacturing sectors. However, investments in analytics, data gathering and management, e-commerce/marketing, intelligence and security will be just as important in the years to come. Investing in the technology skills of human capital, including in the services sectors via education and training, will be key to earning a competitive advantage over companies in advanced economies.

Today’s Challenges

With tailwinds come headwinds that can disrupt and delay, but not derail this transition story. The relatively anemic economic recoveries from the financial crisis of 2008–09 have left most of the North Atlantic-centric economies reeling, with government deficits and ever-larger debt burdens intensified by pre-recession trends, like the aging workforce and the decline of the manufacturing sector.

The resulting rise of the voices of populism, protectionism and economic nationalism, as exemplified by the results of the Brexit referendum in the UK, elections in the U.S. and constitutional referendum in Italy, are not likely to abate any time soon. The upcoming 2017 elections in the Netherlands, France and Germany will heavily test the staying power of the political movements that support globalization, regional economic unions and looser regulation of the cross-border movement of capital and labor.

How policymakers in Asia, Latin America and elsewhere in the growing economies handle this challenge will be key to their own successes in not only avoiding trade wars but also in how the transition in leadership is completed.

Meeting the challenges of an ever-growing and consuming middle class in the growing economies—while simultaneously steering themselves through the challenges facing globalization in the coming decade or so—will need to be the priorities for multinationals desiring to be one step ahead of competitors.

*Countries outside the European Union, Switzerland, Norway, Iceland, United States, Canada, Japan, Australia and New Zealand

This piece originally appeared as part of the inaugural issue of a new Mercer publication titled “Voice on Growth Economies.”