The Great Decoupling: Are Asian Central Banks Breaking from the Fed?

The seal of the Federal Reserve is seen on a U.S. banknote in Washington, DC. During this current Fed hiking cycle (100 basis points since December 2015), no Asian central bank has followed the Fed yet.

Photo: Mandel Ngan/AFP/Getty Images

For a long time now—and particularly since the onset of the global financial crisis—there has been talk about whether Asian economies have started decoupling from the West. With the latest round of rate hikes by the U.S. Federal Reserve Bank, the decoupling phenomenon seems to be finally coming to fruition. However, this may not last.

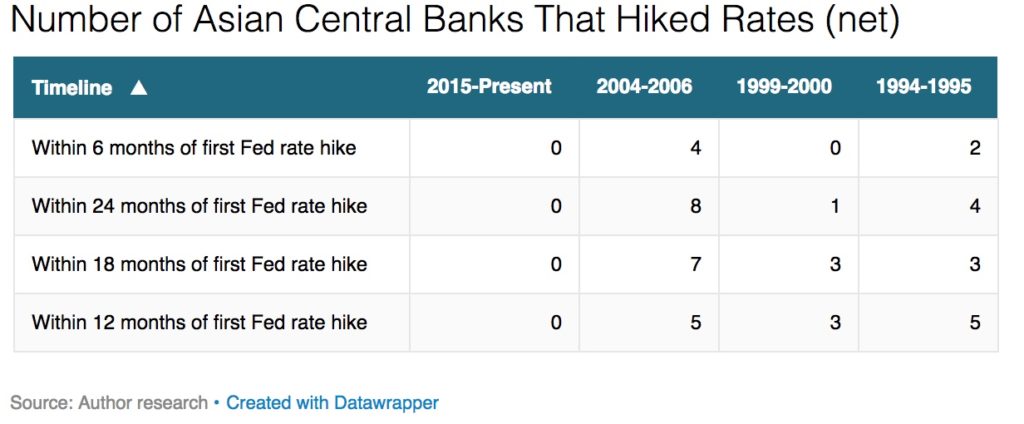

The Fed’s 1994-95 hiking cycle (300 basis points) lasted 13 months, during which time five of the eight major central banks in Asia ex-Japan followed suit. The 1999-2000 Fed hiking cycle (175 basis points) lasted 12 months, with three Asian central banks hiking rates. The 2004-06 hiking cycle (425 basis points) was much longer, lasting 25 months and, by the end, eight Asian central banks had hiked.*

By contrast, during this current Fed hiking cycle (100 basis points since December 2015), no Asian central bank has followed the Fed yet, even though many Asian policy rates are at historically low levels; in fact, this year, the central banks of India and Indonesia cut rates further. This lack of Asian central bank action is an extraordinary departure from past Fed hiking cycles.

Why has Asia Decoupled?

We can think of six factors contributing to Asia’s decoupling:

Low inflation. It could continue as global market competition, automation and so-called “Amazonification” intensify, in line with Asia’s rising technology penetration rates. These structural disinflationary forces, which many attribute to “lowflation” in the West, could be in the early stages in emerging Asia.

More flexible exchange rates. This has been a clear pattern in Asia, and it gives its central banks more leeway to have monetary policies that are independent from the Fed. Asian central banks have become less willing to raise rates to defend exchange rate levels than in the past.

Tighter macroprudential policies. Rather than hiking interest rates, Asia has heavily deployed tools like caps on the ratios of property loan-to-value and household debt-to-income, to contain credit and property market booms.

The European Central Bank and Bank of Japan are still in quantitative easing mode. Amid a slow Fed hiking cycle, this could sustain the global hunt for yield and strong capital inflows to Asia, keeping liquidity flush.

Tail risks. Asia is arguably the most exposed region to a China setback, North Korea or U.S. protectionism. Asia’s central banks may want to take out insurance by keeping rates low.

Debt overhang. The large buildup of private domestic debt in Asia may have lowered central banks’ willingness to hike rates over fears of triggering a wave of credit defaults. A striking fact is that despite policy interest rates being lower now than in 2007, private debt servicing costs are higher today than in 2007 in all major Asian economies.

Asia’s historically low bond yields suggest that these factors are largely priced in. However, with stronger and more synchronized global growth, some of these factors—particularly low inflation and quantitative easing in the EU and Japan—could start to fade. Separately, the recent rise in oil prices could spread to other commodity prices and lift headline consumer price index inflation, which, with mostly adaptive inflation expectations in Asia, could cause core inflation to creep over time. If this occurs, and if Asia’s central banks remain on hold—perhaps due to tail risks and the debt overhang—bond markets may start perceiving them as falling behind the curve.

South Korea—the Canary in Asia’s Coal Mine

The thinking among some Asian central banks is shifting to one of using this window of strong economic growth to raise—or in central-bank speak, “normalize”—interest rates from their current historically low levels, in part to help reduce financial stability risks but also to provide more space to cut rates whenever the next downturn comes.

We recently pulled forward our forecast timing for the Bank of Korea’s first rate hike to November 30, 2017 from the first quarter of 2018. And this week, following Malaysian central bank Bank Negara Malaysia’s more hawkish monetary policy statement, we penciled in a 25 basis point hike by the central bank in January; previously we had no hikes through to 2019.

At this stage, we have no other central bank raising rates until the second half of 2018 (Philippines’ Bangko Sentral ng Pilipinas +50 basis points, Bank of Korea +25 basis points and Central Bank of the Republic of China (Taiwan) +12.5 basis points), but our view is clearly moving in the direction of earlier and more widespread rate hikes in Asia.

If our Bank of Korea call is right, this could mark the start of a hawkish turn by Asia’s central banks. After all, in terms of changing economic trends, Korea is often the canary in Asia’s coal mine.

Testing Times for Asia’s Central Bankers

This is a very challenging period for Asian central banks, as Asia’s business cycle (that is, solid GDP growth but low consumer price index inflation) is fairly muted by historical standards; but thanks to quantitative easing by the world’s main central banks, Asia’s financial cycle (that is, elevated debt levels and property and equity prices) is oversized by historical standards.

It can be difficult to communicate the rationale for monetary policy tightening to the public when consumer price index inflation is low, especially when Asian central banks have for the most part been inflation targeters. However, in our view, Asian central banks need to adapt their policies and “get on” with monetary policy normalization. Otherwise, the next financial crisis could be in Asia.

*We excluded the monetary authorities of Hong Kong and Singapore as, strictly speaking, they are not central banks; due to their managed exchange rate regimes they do not have independent monetary policies.