The Great Economic Inversion: Why Balance Sheets Have Been Turned Upside Down

Shoppers pass by a luxury retail store along Orchard road in Singapore. Balance sheets today are dominated by intangible assets such as brand, IP, code rather than physical assets.

Photo: Roslan Rahman/AFP/Getty Images

Four simple statements I read recently got me thinking:

- Alibaba, the world’s most valuable retailer, has no inventory

- Uber, the world’s largest taxi company, owns no vehicles

- Facebook, the world’s most popular media owner, creates no content

- Airbnb, the world’s largest accommodation provider, owns no real estate

These four statements neatly capture one of the mega trends revolutionizing the global economy. Over the last 40 years, the world has undergone a massive economic inversion. Corporate balance sheets, once cluttered with tangible assets such as property, plants and equipment, have been inverted. Airlines don’t own airplanes anymore. Hotels don’t own their own buildings. Even car manufacturers are now outsourcing production lines.

If all the heavy and tangible assets are gone, what replaces them?

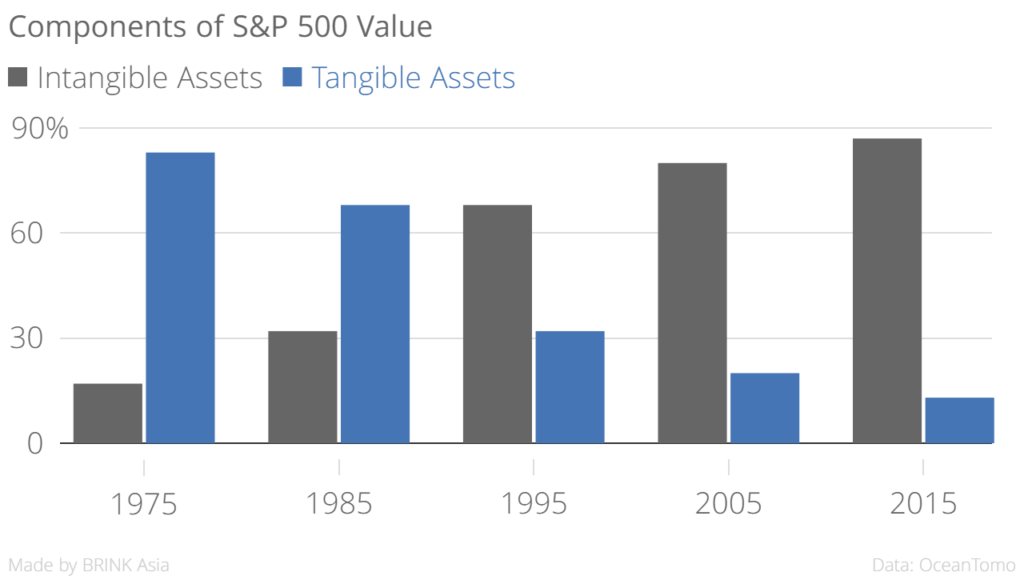

The answer is both profound and simple. Balance sheets today are dominated by intangible assets: brand, content, data, know-how, confidential information, design, inventions, code—in short, intellectual property. A 2015 survey by OceanTomo found that roughly 87 percent of the value of the S&P500 is now in intangible assets.

This makes sense on a microeconomic level, too. Take a company such as Apple or Alibaba or Baidu and calculate the value of all their fixed assets (desks, chairs, laptops and anything else you can physically touch) and it soon becomes clear that all the real value is somewhere else entirely.

It is happening in value chains, too: In a backstreet in China or Indonesia, a T-shirt can be purchased for $1. Sew on a Calvin Klein or D&G label, and the same T-shirt now costs $100. Where did the $99 in value come from? Branding (supported by content, design, innovation, marketing and distribution know-how, which are all intangible assets), yet the “$99 brand contribution” won’t be found in the P&L.

Opportunities and Risks Abound

Despite the enormous impact of this inversion, the financial, legal, accounting and regulatory world is still playing catch up. Hundreds of years of the preeminence of “real” assets in accounting and humans’ innate tendency to focus on the tangible over the intangible means we still tend to concentrate on things we can physically stub our toes on and ignore far more valuable (or dangerous) intangibles.

For example, in due diligence, audit or financing, the counter party or investor typically focuses on what the fixed asset register looks like, yet in many cases it is now largely irrelevant. Traditional company accounts frequently fail to show where real company value now lies. On the balance sheet, intangible asset value—the underside of the proverbial iceberg—is often missing altogether or unceremoniously lumped together under the blunt term “goodwill.”

As management guru Peter Drucker identified: What cannot be measured cannot be managed. Consequently, much intangible asset value goes under-reported, under-valued and misunderstood.

This economic inversion—the movement from heavy (tangible) to light (intangible) balance sheets—presents enormous opportunities and risks, and its effects are rippling—seen and unseen—through the global economy.

The Unintended Consequences of Outsourcing

The outsourcing of manufacturing to Asia that began in the 1990s has been both a driver and reflection of the fact that intangible assets are the most important assets companies own. Faced with declining earnings, Western companies realized that of the three core business functions (design, manufacture, sell), design and sale added the most value, while manufacturing enterprises required significant capital, were prone to volatility and traded at discounts on exchanges.

The solution was to outsource manufacturing to lower cost centers, thereby increasing earnings and freeing up capital. What many did not realize at the time was that this transfer involved more than just physical manufacturing. It also included transfer of critical but underappreciated industrial know-how and design expertise. These intangible assets have subsequently been rapidly utilized, leveraged, and then frequently surpassed by Asian manufacturers to enable them to compete head-to-head in the West’s home markets.

New Forms of Risk

Risks exist as well and can be identified once investors and management begin to investigate the previously unseen.

Many companies and their investors are exposed to currently un-priced or under-priced risk from infringement of third-party intellectual property; failure to own or control intangible assets critical to delivery of major revenue streams; the loss of key intangible assets through theft or lack of management (data, content, confidential information); or are vulnerable to new technology and innovation that threatens core business.

The inversion’s ripples don’t just stop at operating companies, they affect financial institutions as well.

Banks, for example, have traditionally made loans to businesses secured against tangible assets (plant, equipment, real estate). These assets are increasingly irrelevant to company performance. Over time, banks face a stark choice: Either don’t bank a progressively large portion of the market (and watch your book shrink), or figure out how to ascribe value to the intangible assets of your customers. The same assets that current thinking and accounting rules tell you to put a line through are ironically where the real value lies. Investors face similar challenges with banks: Often, modern company performance cannot be fully understood without also understanding the management, risks and opportunities baked into the investee’s intangible assets.

What Are the Implications for Companies?

The great economic inversion that began 40 years ago has profound implications for management, boards, investors and financial institutions.

Management teams need to recognize that intangible assets are the most important assets they control, regardless of what the balance sheet or P&L might say. It is these assets the C-suite needs to leverage to drive growth and increase shareholder returns. Boards need to begin by adding intangible asset risks to the audit and risk committee agenda—to understand that if 87 percent of our assets are intangible, these are also where our largest and most significant risks will emerge from.

Financial Institutions Need To Rethink Existing Credit Models

Current models often fail to reflect the reality of where cashflow really comes from (hint: unless it’s real estate, it’s not the tangible assets), what constitutes “security” and how to recover value from intangible assets in distressed situations. Investors need to understand that existing company reporting is based on accounting standards that were fundamentally designed for a 19th century industrial economy and therefore frequently under-, over- or misstate company performance.

Like boards, investors also need to reconsider risk: Intangible asset risks are materially different from those associated with fixed or tangible assets and need to assessed, managed and mitigated differently. Regrettably, much modern due diligence continues to see intangible asset risk as a small and tangential area. The explosion of cyber risk (just one subset of intangible asset risk) belies that notion.

There Is No Going Back

In a knowledge economy, intangible assets will only become more important. As with any fundamental shift, those who see further and embrace the change are best-prepared to profit from it.