These 3 Maps Explain India’s Growing Water Risks

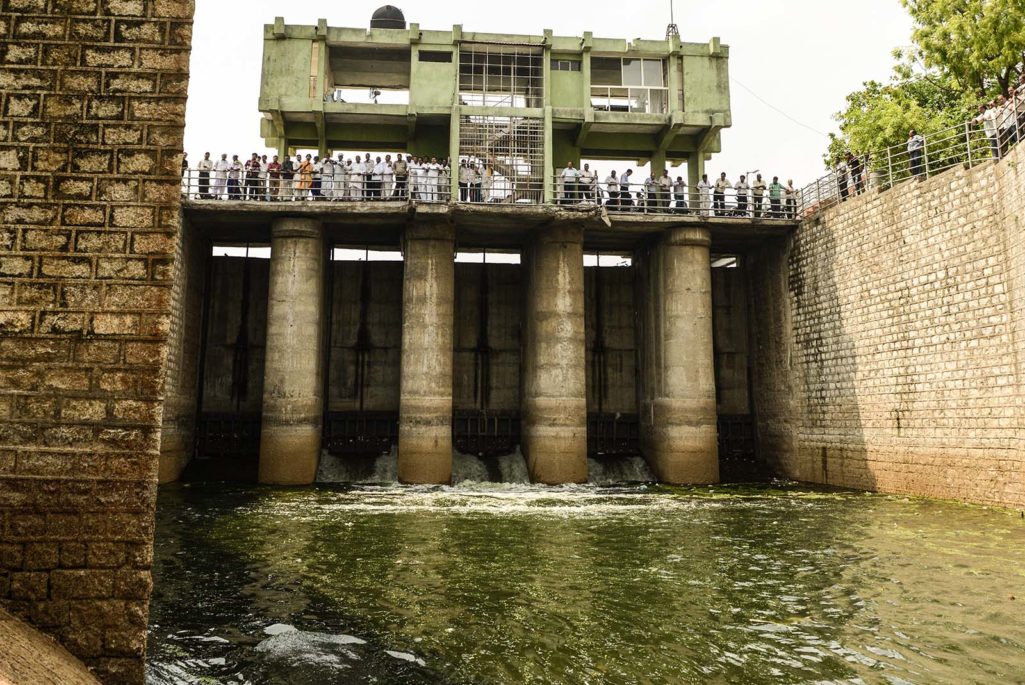

Indian farmers and government officials look on as water is released from the Wasna Barrage for the farming community in Ahmedabad. India's overall annual water consumption is expected to almost double f by 2050, according to the Central Water Commission.

Photo Sam Panthakyd/AFP/Getty Images

India is one of the most water-challenged countries in the world, from its deepest aquifers to its largest rivers.

Groundwater levels are falling as India’s farmers, city residents and industries drain wells and aquifers. What water is available is often severely polluted. And the future may only be worse, with the national supply predicted to fall 50 percent below demand by 2030.

With India’s economic expansion accelerating—its projected 8.5% GDP increase makes it one of the fastest growing economies in the world—companies considering investments there need all manner of tools to help assess the risk of doing business in a land fraught with sustainability challenges. One of those tools is a new, publicly available web platform—the India Water Tool 2. 0—for evaluating India’s water risks. Created by a group of companies, research organizations, and industry associations—including the World Resources Institute and coordinated by the World Business Council for Sustainable Development—the tool can help companies, government agencies, and other water users identify their most pressing challenges and carefully target water-risk management efforts.

Three charts drawn from the tool illustrate trends about the depth and breadth of India’s water-related challenges.

54 Percent of India Faces High to Extremely High Water Stress

This map illustrates competition among companies, farms and people for surface water in rivers, lakes, streams, and shallow groundwater. Red and dark-red areas are highly or extremely highly stressed, meaning that more than 40 percent of the annually available surface water is used every year.

With 54 percent of India’s total area facing high to extremely high stress, almost 600 million people are at higher risk of surface-water supply disruptions.

Note, in particular, the extremely high stress area blanketing Northwest India. The region is India’s breadbasket. The states of Punjab and Haryana alone produce 50 percent of the national government’s rice supply and 85 percent of its wheat stocks. Both crops are highly water intensive.

54 Percent of India’s Groundwater Wells Are Decreasing

Groundwater levels are declining across India. Of the 4,000 wells captured in the IWT showing statistically significant trends, 54 percent dropped over the past seven years, with 16 percent declining by more than 3.2 feet per year.

Farmers in arid areas, or areas with irregular rainfall, depend heavily on groundwater for irrigation. The Indian government subsidizes the farmers’ electric pumps and places no limits on the volumes of groundwater they extract, creating a widespread pattern of excessive water use and strained electrical grids.

Northwestern India again stands out as highly vulnerable. Of the 550 wells studied in the region, 58 percent have declining groundwater levels.

More than 100 Million People Live in Areas of Poor Water Quality

Only 9 percent of India’s 632 groundwater quality districts are at acceptable government levels, as set by the Bureau of Indian Standards (BIS), according to the IWT.

Whenever a particular pollutant concentration exceeds BIS limits, drinking water is considered unsafe. The yellow and red areas on the map below indicate places where chlorine, fluoride, iron, arsenic, nitrate, and/or electrical conductivity exceed national standards.

These districts are also extremely populous; 130.6 million people live in districts where at least one pollutant exceeded national safety standards in 2011. And more than 20 million people lived in the eight districts where at least three pollutants exceeded safe limits. Bagalkot, Karnataka, is the most polluted, with five of six groundwater quality indicators at unsafe levels, only arsenic falls below the government-recommended concentration level.

Proactive, Innovative Management Is Critical

The IWT was specifically designed to help companies, government agencies, civil society organizations, and other stakeholders assess water risks, a critical first step toward reversing the damage already done to India’s water supplies and protecting against chronic struggles.

Users can upload or enter hundreds of GPS-based locations. For each location, the tool will produce values quantifying water stress, groundwater depletion, current and projected groundwater availability, water quality, rainfall and more. The tool can also create a map showing all the uploaded locations, which can either be kept private if the information is sensitive or exported as a communications product or as a visual for a corporate disclosure initiative. For example, India’s state and national governments could use the tool to understand threats to surface and groundwater water security, and therefore support long-term development planning and conservation planning.

Tools like the IWT may only be a first step in a long process of risk reduction and mitigation, but they are essential. Only with ongoing efforts to improve data transparency and accessibility can India advance toward a sustainable water future.

WRI’s Andrew Maddocks, Christopher Carson and Emma Loizeaux also contributed to this piece.

This post is adapted from a blog that originally appeared on WRI Insights.