To Switch or Not To Switch: Australia’s Big EV Question

Data shows not only that Australian sales of EVs are insignificant but that they are also declining.

Photo: Cameron Spencer/Getty Images

Australians have been keen adopters of many innovative technologies but not the electric vehicle (EV). Data shows not only that Australian sales of EVs are insignificant but also that they have been declining.

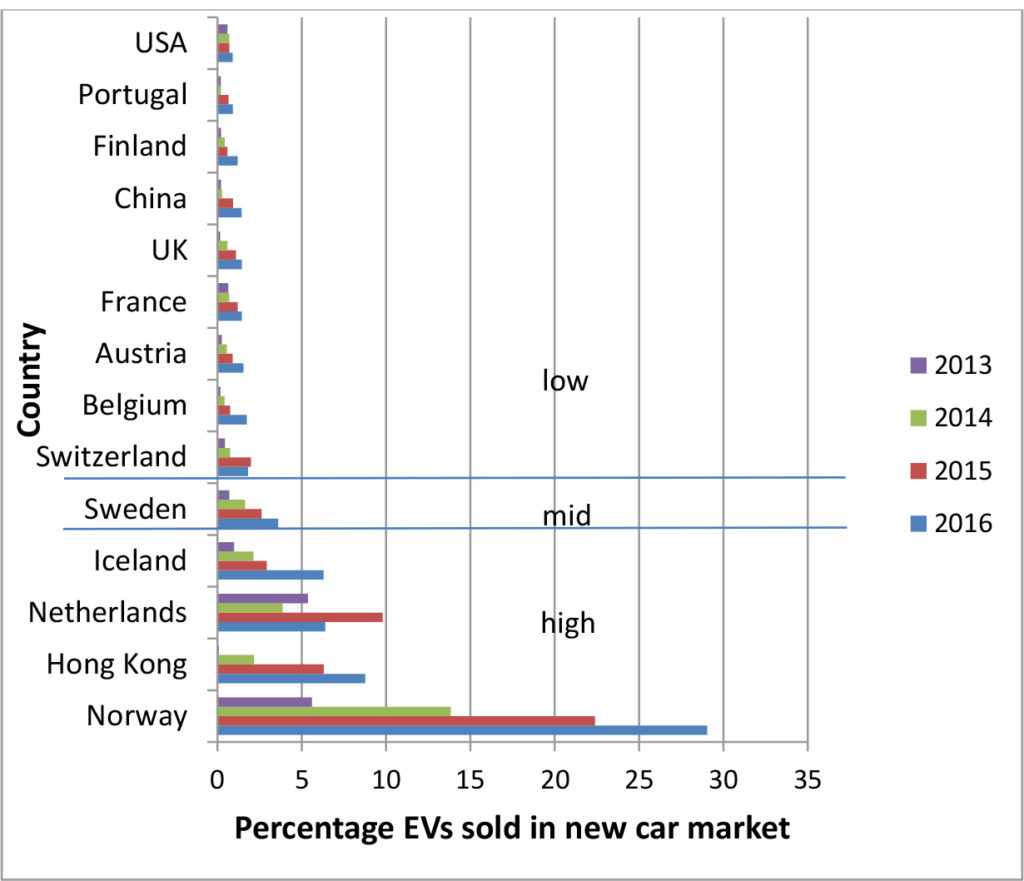

This is in direct contrast to many European countries, especially Norway, and some states of the U.S., such as California, where new car sales are increasingly electric (see exhibit). The figures for Australia, at less than 0.1 percent, are so low that they wouldn’t be apparent on this graph.

Exhibit: Percentage of EVs Sold in Select Car Markets

So what is stopping Australian consumers from taking up this opportunity to rein in their weekly transport bills?

The Reasons and Potential Solutions

Current research has demonstrated three main factors that hinder EV uptake: high vehicle price, lack of recharging opportunities and lack of consumer knowledge about alternatives to conventional vehicles.

High vehicle prices are an obvious barrier, but our surveys of Australian motorists’ attitudes using online questionnaires have shown this is not the most important consideration. The essential ingredient that could encourage uptake is the rollout of a comprehensive network of recharging stations, particularly on the popular intercity routes, and it seems to be more important than subsidizing vehicle purchase price.

Rechargers on highways, at service centers and in country towns will need to be fast and convenient so that motorists can continue their journeys without undue delay, and there should be no need to join a network—just tap and go.

California is the model for this legislation. We will also need an app so that motorists can use their phone to locate charging stations. Without the right charging infrastructure to provide the necessary market co-conditions there would be no basis for Australians to go electric with confidence.

Australians usually drive short distances on a day-to-day basis, with daily averages of just 36 kilometers, well within the range of modern fully electric vehicles on offer today. However, many Australians go for the occasional long trip throughout the year, and they want to be able to continue to do so without having to be unduly inconvenienced. By comparison, Norwegians—the most enthusiastic EV adopters—drive an average of 40 kilometers a day. The Norwegian government has supported the necessary infrastructure, and now Norwegian EV drivers can access the highest proportion of public rechargers in the world. But the world leader in recharger rollout is Estonia. It is credited as the first nation to build a country-wide network with a recharging station every 50 kilometers on major roads and at least one in every town with a population over 5,000.

To be ready for the transition to electric driving, we not only need an adequate network, we need standards for the recharging plug hardware. There are quite a few plug types, so to avoid unhappy investors and motorists, who don’t want to fuss about finding a recharger with the right plug type, this issue needs to be resolved.

As battery developments continue, the driving range of newer model EVs will keep increasing. However, due to the unique journey of every motorist, rechargers will be needed every 100 kilometers or so. In Europe, recharge stations return any investment due to allied sales when motorists stop for a break, and there is no reason why Australia can’t follow suit.

While a nationwide network of rechargers will be essential, most people will recharge at home overnight. So we need to reassure potential EV customers that they will be able to arrange for this. Not everyone has a garage or parking space with easy access to a power point to enable overnight recharging. With apartment living on the rise, we need to ensure that access to a power point is a given. Ideally, federal government regulations would be put in place so that apartment dwellers don’t become the electric car have-nots. California has legislation that is inspirational in this regard.

Furthermore if electricity is cheaper at night, ensuring that consumers can access off-peak pricing could allay any fears about EVs overloading the grid during times of peak electricity demand. With off-peak pricing, people will act in their own financial self-interest and get into the habit of turning on the recharger switch when they go to bed. Some federal regulation would be welcome to ensure this service would be available to all.

Australia Needs To Switch to EV

Getting everyone to go electric as quickly as possible will save billions in imported oil. In 2016, refined petroleum imports cost Australia almost AU$15 billion ($12 billion), and much of it was used for road transport. The money saved would help reduce foreign debt and would fund infrastructure.

Recently, Josh Frydenberg, the Australian minister for the Department of the Environment and Energy, wrote that while electric cars are getting cheaper, the single biggest factor affecting EV purchase price is the cost of the battery. With improvements in technology and falling production costs, it is predicted that EVs will be equivalent in price to similar-model conventional combustion cars within a few years. Charging with electricity is cheaper than filling up with petrol or diesel, especially if home solar is taken into account.

Other hidden costs from using fossil fuels to propel cars also need to be factored in. Hospital costs from illnesses caused by using petroleum, such as cancer and asthma, is just one example. Australia is one of the only developed countries in the world to not have minimum fuel efficiency standards, and this has a direct impact on the type of vehicles imported into the country. Australia continues to act as a dumping ground for inefficient models and provides no incentive for brands to increase sales of EVs to meet standards.

For years, Norway has led the charge toward electrification of the car fleet. In 2017, EVs comprised an astonishing 35 percent of new car sales in Norway—in no small part due to an excellent public recharge network.

Yet, even in a country that has supported the transition to EVs for more than two decades, owners of conventional cars without any exposure to EVs are three times more concerned about running out of charge on a long trip than EV owners. Moreover, Norwegians who didn’t have any friends who owned an EV were far less likely to consider buying one.

This highlights the importance of providing practical exposure to electric cars and increasing consumer awareness about alternatives to traditional vehicles. Providing basic experiences driving a car, as well as accurate information about costs and driving range well before car customers arrive at the point of sale, is likely to increase adoption.

The market can’t be relied on to create an EV revolution in Australia. Funding infrastructure and making it easier to use, creating standards, implementing legislation to reward cheaper and less polluting cars, and providing opportunities for people to learn about exciting developments will be part of the challenge.

The authors would like to acknowledge the contribution of Dr. Danielle Drozdzewski to this article.