Robotics Improves the Fate of Demographic Decline in Japan

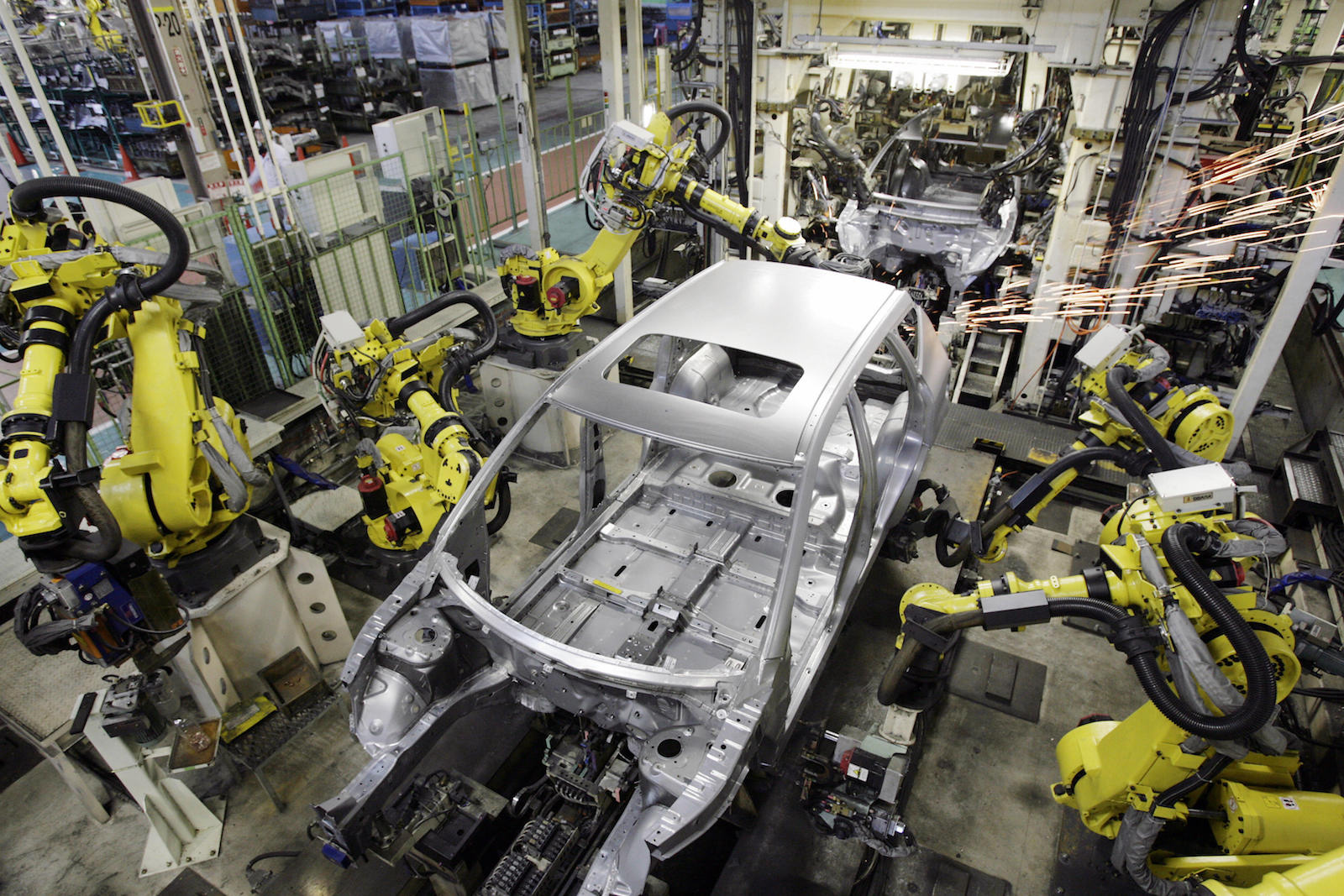

Welding robots work on vehicles at an assembly line in the town of Karita, on Japan's southern island of Kyushu. In Japan, advanced robotics is helpful in dealing with demographic decline.

Photo: Yoshikazu Tsuno/AFP/Getty Images

Advanced robotics and other technologies of the Fourth Industrial Revolution are striking fear among workers in many Western countries. Rapid technological change and globalization have been displacing jobs and contributing to income inequality—and the concern is that this will only continue.

It has even been argued that robots could spell the end of the Asian Century. Indeed, as the labor component in production is increasingly replaced by robots and other technologies, the incentive to outsource production to emerging Asian economies to take advantage of low labor costs will be reduced.

Robotics in Japan

In sharp contrast, the case of Japan seems more positive. Indeed, advanced robotics is proving to be very helpful in dealing with its demographic decline; and all the more so since the cost of robots has been falling and their sophistication improving.

Japan’s fertility rate has been significantly below the “replacement rate” of 2.1 children per woman since 1974 and is currently only 1.4. As a consequence, its working age population has been declining since 1995 and is projected by the United Nations to fall by 24 million between now and the year 2050—a figure well in excess of Japan’s traditionally very low levels of immigration.

This is where advanced robotics come in. Robotics played a critical role in Japan’s postwar economic rise, especially in the automotive and electronics sectors. More recently, robotics have been filling some of the gap in Japan’s shrinking working age population, especially in the country’s highly efficient manufacturing sector. And, robotics may even be lifting GDP and wages.

Indeed, the OECD estimates that Japan has the second most robot-intensive economy in the world, in terms of industrial robots measured against manufacturing value added. It is well ahead of Europe, the U.S. and China and is only surpassed by South Korea. And according to the International Federation of Robotics, Japan is the world’s predominant industrial robot manufacturer, producing 55 percent of the global supply, with companies like FANUC, Kawasaki Heavy Industries, Sony and the Yaskawa Electric Corporation leading the way.

Robotics Pervading Critical Sectors

Convinced that robotics can play a key role in responding to the country’s aging population, the government launched Japan’s Robot Strategy as part of the revised 2014 Japan Revitalization Strategy, with a clear focus on speeding the adoption of robots in sectors with low productivity, particularly nursing, agriculture and infrastructure construction.

While robotics have long been part of Japan’s world class manufacturing sector, robotics are beginning to sweep other parts of the economy and society, like Japan’s highly protected and inefficient agricultural sector. This is of critical importance as Japanese agriculture is facing impending extinction, with a growing number of fallow and abandoned agricultural fields.

Working with robots means education and training systems need to adapt, and workers need to be willing to continue with education and training.

Since 1985 Japan’s farming population has shrunk by around 60 percent, while the average age of people primarily engaged in agriculture has increased by 7.2 years over the past decade to 67. These trends are pushing robotization and automation into the agricultural sector. For example, Spread Co., Ltd’s Techno Farm Keihanna is reportedly the largest automated vertical farm in the world, with an automated cultivation system capable of producing 30,000 heads of lettuce every day. It started shipping its products in November 2018.

Japan’s services sector, whose productivity lags far behind the manufacturing sector, is also being transformed by robotics, in sectors such as finance, retail and hospitality. For example, there are reports of hotels being staffed by robots, like the Henn na Hotel, east of Tokyo, where there have been robots operating the front desk. But the Henn na group has also encountered some challenges in the robotization of its hotels. Following numerous complaints from staff and customers, the chain has now culled over half of its 243 robots, because they created work rather than reduced it.

Robots are also being used in Japanese hospitals and elsewhere in the health care industry. And humanoid social robots, like Softbank’s “Pepper,” are being promoted as social partners for Japan’s aging population, as well as people in need of a friend.

Finding the Sweet Spot

Has Japan found a sweet spot with the coincidence of its aging population and its robotics revolution?

Advanced robotics do hold great promise for dealing with the country’s demographic dilemmas, as they can fill the gap left by Japan’s declining workforce, perform new and varied services required in an aging society and offer improvements in productivity. But robotics also presents new challenges.

In particular, people working with robots will often require new, different and more sophisticated skills. And in rapidly aging Japan, this will require retraining of older workers. This means that education and training systems need to adapt, and workers themselves will need to be willing and able to continue with education and training.

As daunting as this might seem, in Japan’s case, the prospects are relatively positive, based on the OECD’s survey of adult skills. Adults in Japan displayed the highest levels of proficiency in literacy and numeracy among adults in all countries participating in the survey. In the assessment of problem solving in technology-rich environments, the performance of Japanese adults was around average, while younger adults performed lower than average in this domain.

The OECD also noted two other concerns that should be addressed. First, Japanese women with their high levels of proficiency in literacy and numeracy remain an underused resource, despite the government’s chanting of “womenomics.” Second, Japanese employers do not appear to be making the best use of their workforce’s competencies.

In other words, Japan still has much to do to realize a robotics sweet spot.