Digitization Could Finally Transform Japan’s Economy

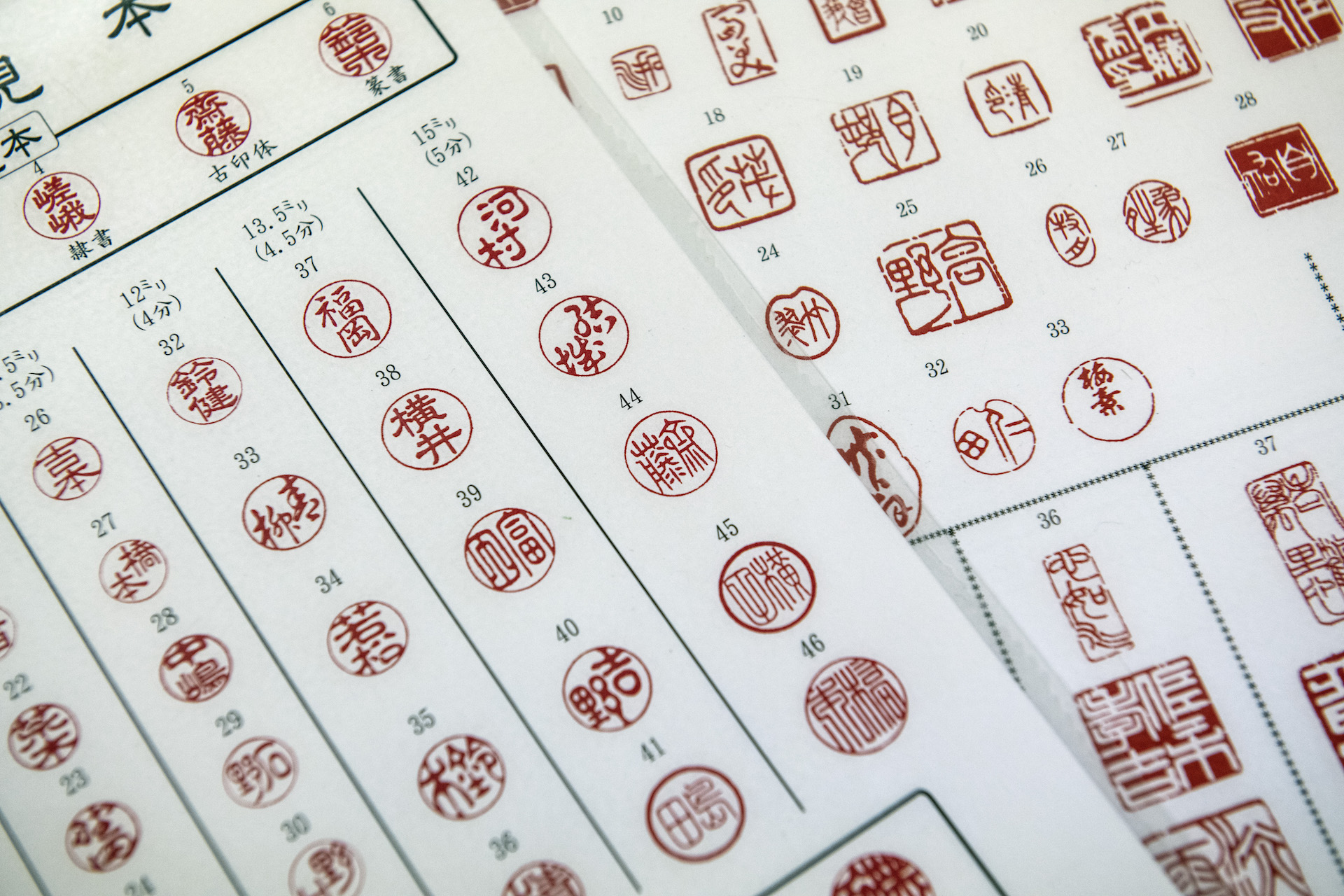

Hanko name stamp designs are displayed in the Sano Inbo hanko shop on October 21, 2020 in Tokyo, Japan. Traditional hanko stamps are still in use in Japan instead of e-signatures.

Photo: Carl Court/Getty Images

Japan is well-known as a high-tech country. It is, after all, the home of bullet trains, robots and computer games. But there is another side of the story: low-tech Japan.

While most of the world communicates by email, our Japanese friends are still hooked on fax machines. While the rest of us use electronic signatures, the ancient tradition of personal red seal stamps (“hanko”) persists in Japan. And cash still dominates consumer purchases to the great surprise of foreign visitors, especially from China whose large cities are increasingly cashless.

COVID Exposed Japan’s Low-Tech Approach

A recent report from the OECD pointed out that in Japan “the pandemic revealed weaknesses as households, firms and government struggled to make use of digital technologies.” Throughout the COVID-19 waves, colleagues of mine in Tokyo rushed to the office, in crowded trains, to pick up faxes or to stamp documents.

In a country where the government has played a leading role in economic development, government use of digital tools is astonishingly low. The OECD reports that less than 10% of individuals use the internet to submit filled forms to public authorities’ websites, compared with 30%, on average, for the G-7 countries. It’s remarkable to see walls upon walls of paper filing systems in my university’s offices.

Many countries fear that digitization will cause their workforces to be replaced by robots and other technologies. But Japan is in a unique — and fortunate — situation. Rather than putting people out of work, digitization could fill labor shortages in the aging economy and give some new momentum to the economy.

Japan’s Aging Population

Japan has led the world in aging due to low fertility and rising life expectancy. Japan’s fertility rate, currently around 1.4 children per woman, has been below 2.1, the rate at which the population replaces itself over time, since 1975. As a result, Japan’s working age population has been declining since 1995, and its total population could fall from today’s 125 million to 75 million by the end of the century.

Naturally, less workers means a weaker economy, and in recent decades, Japan’s economic growth has only averaged about 1% annually, while life expectancy has leapt from 68 in 1960 to 85 years today. This exerts an enormous weight on the government budget and the economy, as Japan now has the highest old-age dependency ratio of all OECD countries.

Social spending has caused Japan’s government debt to balloon to around 250% of GDP, the highest of all OECD countries.

Higher Economic Growth

COVID-19 spurred the adoption of new technologies in Japan. Breaking with the past, growing numbers of Japanese “salarymen” (and increasingly, “salarywomen”) have been working online part of the week from home.

This digital adaptation in the context of COVID-19 is just a beginning. But it has the potential to accelerate and move Japan onto a higher economic growth trajectory.

This could signal the beginning of a performance-based work culture and a welcome end to Japan’s hidebound corporate and bureaucratic ideologies. Electronic commerce is up, with more consumers buying online. Online learning, once a rarity in Japan, is now sweeping through its education sector. Conferences are frequently held by Zoom, exposing Japan’s traditionally insular academic sector to the world.

This digital adaptation in the context of COVID-19 is just a beginning. But it has the potential to accelerate and move Japan onto a higher economic growth trajectory.

A highly educated workforce is key to success in digitization, and Japan ranks very highly in international league tables for education. For example, 15-year-old Japanese students scored particularly well for science, mathematics and, to a lesser extent, reading in the latest OECD’s Program for International Student Assessment (PISA).

Low Levels of English

However, the OECD reports that Japanese students’ digital skills are weak because of insufficient focus on new technology in school curricula. Moreover, relatively few Japanese students study STEM (science, technology, engineering and maths) disciplines, particularly women and girls. Japan will need to better develop education for digital skills to reap the potential rewards of digitization.

Retraining workers is also another imperative, especially as a growing number of seniors are remaining in the workforce and women are returning to paid employment after raising a family. Greater efforts are also necessary to provide digital retraining opportunities to “nonstandard employment” (such as casual or short-term work), as they are all too often excluded from in-house retraining.

Countries like the U.S., the U.K. and Australia have shown that skilled migration can also be a motor for digitization of the economy. And despite its reputation for a closed society, over the past three decades, the number of foreign residents in Japan has tripled to almost 3 million (2.3% of the total population).

In recent years, Japan has been attracting a growing number of migrants, including from India, to fill skill gaps, notably in the IT sector, with approximately 40,000 Indians currently living in Japan.

But the capacity of Japan to profit from this development is hindered by lingering anti-migrant sentiments and poor English language skills — Japan’s population is judged to have “low proficiency” in English, ranking 78 out of the 112 countries in the EF English Proficiency Index, conducted by Education First, a global education company founded in 1965. Japan’s education must place greater emphasis on improving its language skills and cross-cultural sensitivities.

A Great Opportunity for the Country

Somewhat surprisingly, digitization in Japan’s private sector is a mixed bag. The use of digital technologies in large manufacturing enterprises is among the most advanced worldwide. But in smaller enterprises and the services sector, it is quite a different story. Investments in IT resources are often lacking, while weak business dynamism hinders the diffusion of new technologies and management methods.

The government has created a “Digital Agency” to help create impetus for other parts of government. This is critical as the machinery of government plays an important and growing role in citizens’ lives. Seniors, in this aging society, are in regular contact with public agencies for their social security and medical and long-term care. And in this natural disaster-plagued country, citizens need to be hooked into government information and assistance services, especially in the current context of COVID-19.

Digital transformation represents one of Japan’s greatest opportunities and challenges. Digitization could help bring under control Japan’s enormous public debt and lift its flagging productivity which is 20% below the OECD average.

As the Lowy Institute Asia Power Index highlights, Japan has been losing ground relative to China and now falls just short of the major power threshold of the index. Digitization provides a pathway to improving both Japan’s economic and military capabilities and thus strengthening its comprehensive power.