The Revolution Occurring in Japan’s Defense Posture

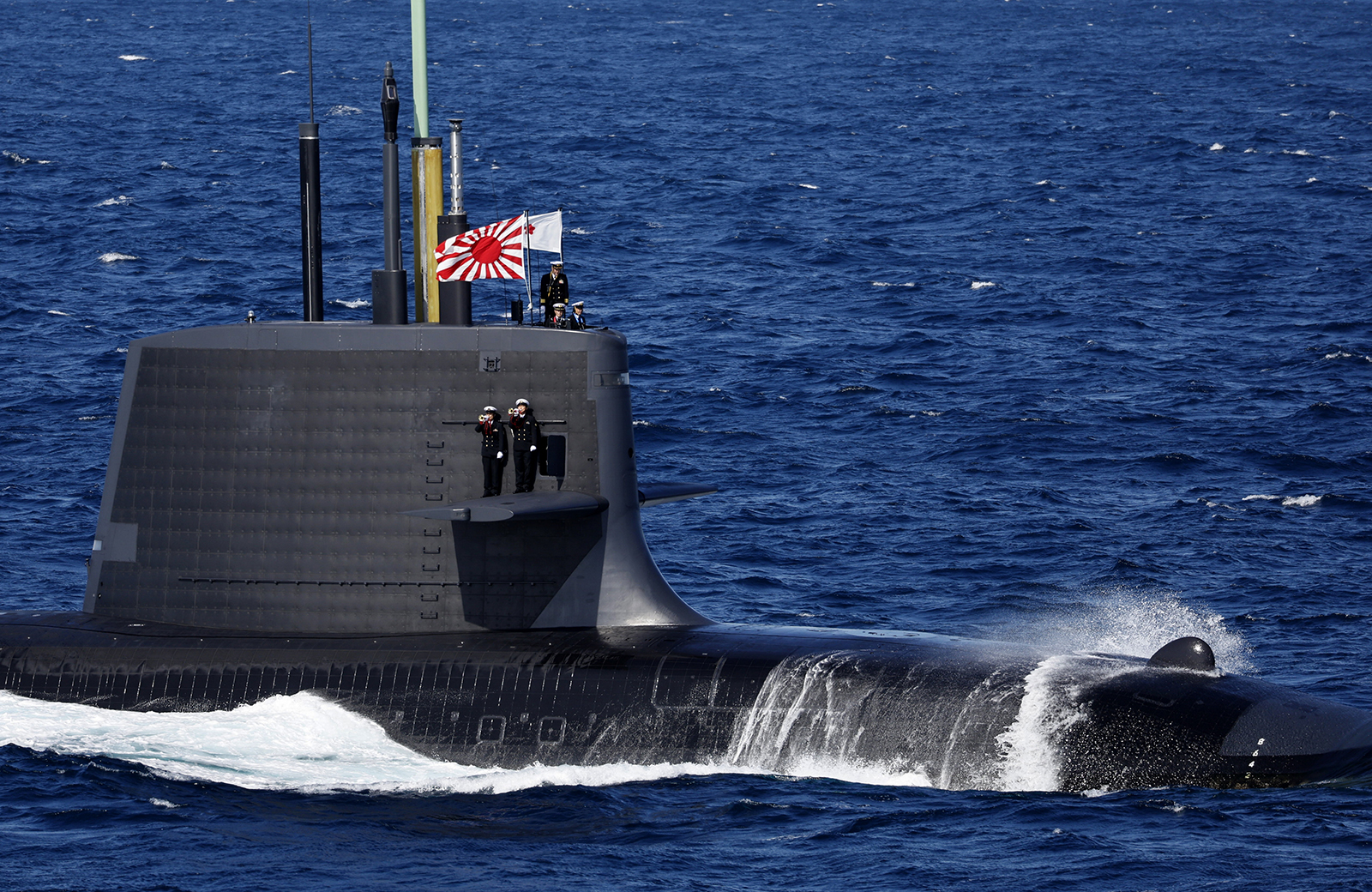

The Japan Maritime Self-Defence Force Uzushio-class submarine participates in an International Fleet Review commemorating the 70th anniversary of the founding of the Japan Maritime Self-Defence Force at Sagami Bay near Yokosuka, Japan, on November 6, 2022.

Photo: Issei Kato / Pool/Getty Images

Following the end of World War II, Japan adopted a rather low-key approach to national security and defense. Under a constitution written by the postwar American occupiers, Japan forever renounced “war as a sovereign right of the nation and the threat or use of force as means of settling international disputes.” Although Japan also agreed to never sustain armed forces, it has long had “Self-Defense Forces.”

Japan’s national security has been substantially ensured by the U.S./Japan military alliance. Thus, Japan only spends 1% of GDP on national defense, much lower than the U.S.’s 3.7%, and the NATO countries commitment to spend a minimum of 2% of GDP.

This facilitated Japan’s rapid development during the early postwar years, as it enabled Japan to concentrate on reconstructing its domestic economy. As a consequence of the nuclear bombing of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, Japan has also long had a vibrant anti-nuclear, pacifist movement.

Former Prime Minister Shinzo Abe Signaled a Hardening of Attitudes

Japan’s security and defense posture gradually began to change with the end of the Cold War, and especially during Former Prime Minister Shinzo Abe’s second term as prime minister, from 2012 to 2020.

Former Prime Minister Abe led the world in defining the new era of competition with China and was well ahead of the U.S., which was still employing “strategic engagement” with China until the end of the Obama administration.

Former Prime Minister Abe’s administration undertook many initiatives in the security and defense realm. It increased Japan’s defense spending modestly, after almost a decade of decline. It secured a new interpretation of Japan’s pacifist constitution, such that Japan could henceforth engage in “collective self-defense,” allowing it to come to the aid of a close ally like the U.S. under attack. It created a centralized national security agency and enhanced international partnerships, especially with India, Australia and Southeast Asia.

Former Prime Minister Abe also advanced the concept of the “Free and Open Indo-Pacific” to defend maritime space from Chinese hegemony. He promoted the Quadrilateral Security Dialogue (Quad), involving Australia, India, Japan and the U.S., which now meets at the leader level.

In response to China’s Belt and Road Initiative, Former Prime Minister Abe launched the Partnership for Quality Infrastructure, and Japan is now a more important investor in infrastructure in the ASEAN group of countries than China. After two lost decades, Japan launched the “Abenomics” program to revitalize the economy, a key foundation for national security.

There is always the risk that Japan could return to the ‘revolving-door’ scenario, such as during 2006-12 when Japan had six different prime ministers, none of whom were in power long enough to make great achievements.

The Revolution in Japan’s Defense Strategy

In December 2022, the Japanese government took a giant step forward when it announced an unprecedented step-up in Japan’s security and defense strategy, through three new documents — the National Security Strategy (a followup to Japan’s first-ever NSS released in 2013), the National Defense Strategy, and the Defense Buildup Programme.

Among the main points are:

– The new NSS identifies China as “the greatest strategic challenge” facing Japan, labels North Korea “an even more grave and imminent threat to Japan’s national security than ever before,” and reiterates Tokyo’s strong stance against Russia’s invasion of Ukraine.

– Traditionally pacifist Japan plans to double its defense spending, from 1 to 2% of GDP over the next five years. This would lift Japan from ninth to third among the world’s leading countries in terms of military spending. And Japan could become a normal military power for the first time in the postwar period.

– Japan will focus on long-range missiles that provide a “counterstrike” capability to preempt enemy attacks, by targeting military infrastructure inside an adversary’s territory. Initially these will be “Tomahawk” missiles imported from the U.S.

Japanese defense planners now believe that Japan’s security environment is the worst of any time since World War II and one of the worst of any country in the world. It is surrounded by China, North Korea and Russia, as well as sitting next door to Taiwan, which is under threat of a Chinese invasion, while joint exercises by the Chinese and Russian militaries near Japan have become more frequent.

China’s military spending has now risen to five times that of Japan’s, while North Korea’s nuclear capabilities have expanded substantially. However, what has changed most has been Russia’s invasion of Ukraine.

The notion that a land war could take place in the 21st century has delivered a great shock to Japan — if it is possible in Europe, it’s also possible in East Asia. All the more so now since President Xi Jinping is commencing his third five-year term. There is obvious concern that President Xi could make rash decisions, with tragic effects for the world, like President Vladimir Putin’s invasion of Ukraine.

How Will This Be Paid For?

As significant as a doubling of military spending may seem, governments around the world frequently fail to deliver on such promises. So there are concerns that Japan may follow suit, as well as employ budgetary tricks to pump up the numbers. Further, Japan’s defense needs are so vast — from cyber and space to unmanned systems and integrated air missile defense — that there is a risk that new spending could be spread too thin, as different constituencies jockey for a slice of the pie, thereby diluting its effectiveness.

Another problem is the financing. The government is planning to finance the rise in military spending by increasing taxation. But there are many political voices opposing this — all the more so given that tax hikes in the past have presaged economic recession.

The alternative of using increased debt is equally unpalatable in this country with government debt of 260% of GDP, by far the highest of any advanced country. Further, there is a desperate need to resuscitate the “Abenomics” economic reforms of the now-deceased former Prime Minister Shinzo Abe — a stronger economy is a sure way for a country to improve its national defenses.

Tackling these thorny issues will require strong and effective leadership, like that demonstrated by former Prime Minister Abe. But the current Prime Minister Fumio Kishida’s approval has recently fallen to record-lows. And there is always the risk that Japan could return to the “revolving-door” scenario, such as during 2006-12 when Japan had six different prime ministers, none of whom were in power long enough to make great achievements.

That said, Japan’s defense and national security plans are truly unprecedented in historical terms. And the broad societal consensus on the dangerous nature of Japan’s neighborhood could help sustain increased military spending, even in the case of a revolving-door of prime ministers. There could also be major benefits, such as through the prospect of the modernization of Japan’s military industry, through increased funding for R&D and further loosening of export rules.

Japan’s Plans Not Taking Place in a Vacuum

Other countries in the Indo-Pacific — like Australia, India and South Korea — are also improving their military capabilities, along with tightening cooperation with the U.S. in the face of the region’s dangerous security environment and lingering concerns about the U.S.’s commitment to the region over the longer term.

The U.S. government hailed “Japan’s new security strategy as a ‘bold and historic’ step to help maintain peace in the Indo-Pacific, with the key Asian ally forging ahead with its biggest defense buildup plans since World War II amid China’s rise and North Korean threats,” as reported by Kyodo News. Not surprisingly, China has expressed its opposition to Japan’s strategic overhaul.