10 Years After the Lehman Collapse—Why Are the Shockwaves Still Being Felt?

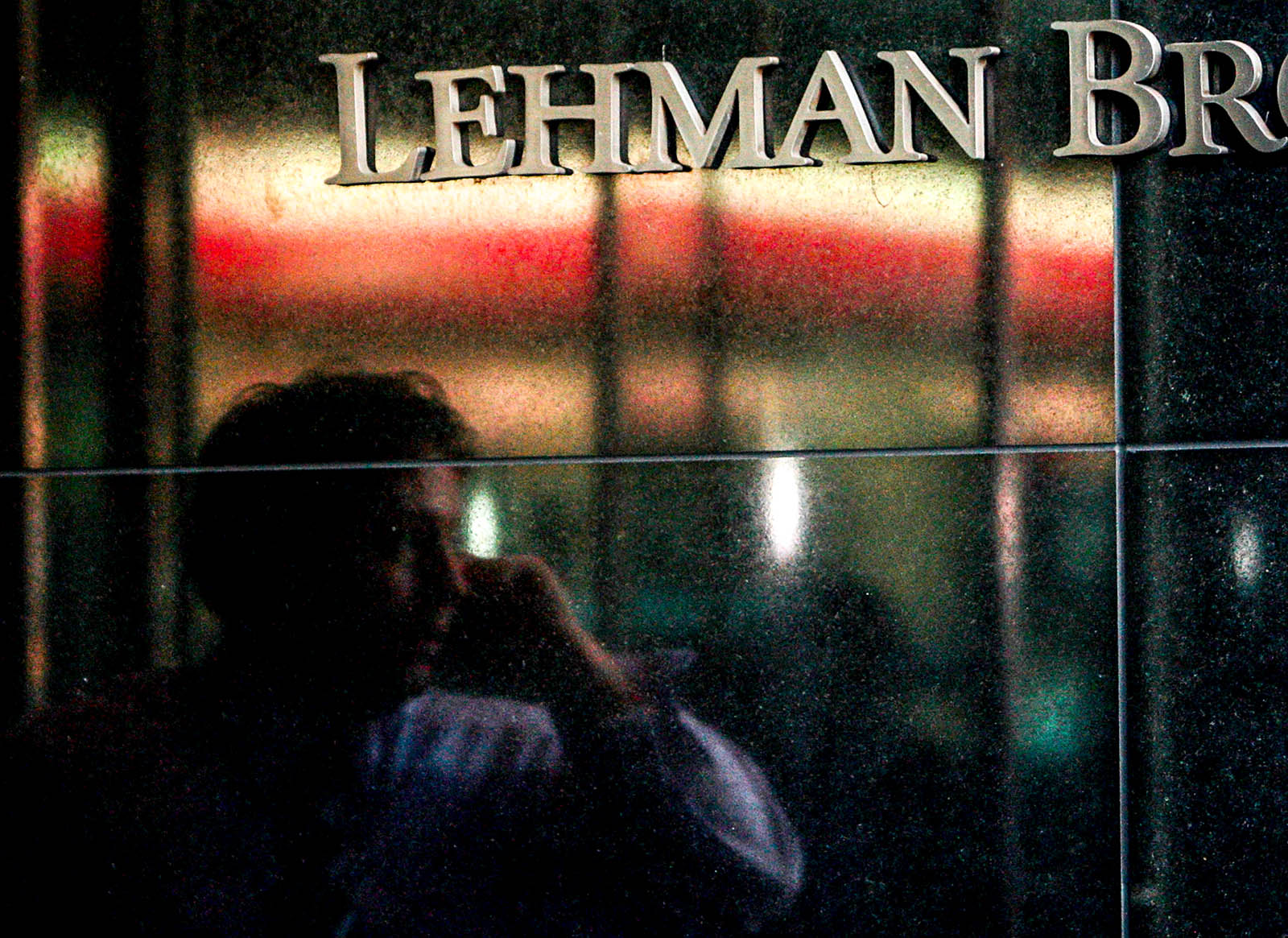

A man speaks on his phone as he stands outside the headquarters of the financial firm Lehman Brothers Holdings Inc., on September 15, 2008, in New York City. Ten years later, many advanced economies have not recovered.

Photo: Chris Hondros/Getty Images

When talk began of a credit crunch or subprime-mortgage crisis in the U.S. housing market in 2006 and 2007, most economists remained relatively calm. The Great Moderation—the end of large swings in macroeconomic variables—was accepted orthodoxy and there was widespread confidence that a way would be found to maintain economic stability.

Many finance professionals were similarly confident, arguing that any potential disruptive event would have to be uncharacteristically disruptive to have a substantial impact.

Such an event occurred little more than twelve months later.

On September 15, 2008, Lehman Brothers declared bankruptcy, was denied a government bailout and, hence, collapsed—possibly the largest disruptive event in financial market history. The Lehman collapse turned a credit crunch into a global financial crisis.

The Shockwaves Are Still Being Felt

Ten years later, the sizes of many advanced economies, as measured by GDP adjusted for inflation, remain far from the levels implied by the growth rates that prevailed before the global financial crisis.

Measures of GDP in the U.S., the UK, and the euro area are still 12 percentage points lower than the levels implied by their respective pre-crisis trends (Figure 1). With little sign of “catching up” to pre-crisis trends, estimates of trend output—the long-run level of output net of transitory business cycle factors—have been repeatedly revised downward in many advanced economies.

This reflects a worry among policymakers that economic activity will not return to previously expected levels.

Figure 1: UK Actual GDP and Trend GDP Estimated from a Linear Trend over 1995-2007

Figure 2: U.S. Actual GDP and Potential GDP from January 2007 CBO Estimate

Figure 3: Euro Area Actual GDP and Trend GDP Estimated from a Linear Trend over 1995-2007

Will We Ever Get Back?

The underlying reasons for the persistent gaps between current GDP and its pre-crisis trend are not fully understood.

Economists have put forth a number of possible explanations such as:

- Slower than usual technological advancement

- A shift to less capital-intensive industries

- Demographic change

- Increasing economic inequality

- Potentially long-lasting effects of the global financial crisis

In a new working paper, we focus on the last option: the extent to which the financial market disturbances in 2007 and 2008 have caused some of the persistent gaps between current GDP and its pre-crisis trend. While our main results are for the U.S.—and are summarized in a recent Economic Letter published by the Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco—we can also apply our approach to the UK and the euro area.

We find that a large fraction of the gaps between GDP and its pre-crisis trend level is due to the 2007-2008 financial market disturbances and that the GDP figures are unlikely to catch up with the levels implied by their pre-crisis trends.

Financial Markets and the Real Economy—an Asymmetric Relationship

One important difficulty in studying the effects of financial market conditions on the economy is that the relationship is likely to be asymmetric. When the economy is in good shape, an adverse financial shock—a disturbance that limits the risk-bearing capacity of financial intermediaries—likely prevents firms from obtaining financing for profitable investment opportunities and therefore reduces economic activity. On the flip side, when the economy is doing poorly, an increase in credit supply may not raise economic activity if there are no investment opportunities.

In contrast to previous empirical work, our model allows for the possibility that the relationship between economic activity and financial markets is asymmetric. Consistent with economic theory and the intuition laid out above, we find that an easing of financial market conditions has little effect on economic activity. A tightening of financial market conditions, on the contrary, has significant and highly persistent effects on economic activity.

Where Would We Be if the Global Financial Crisis Had Never Happened?

Our model exploits variation in financial market conditions and economic activity over time to calculate how they typically interact over the business cycle. Following this approach, we can infer how the economies would have performed without the financial market disruptions in 2007 and 2008.

We find that GDP figures would have remained much closer to their pre-crisis trends.

In the U.S., the 2007-2008 financial shocks can account for 7 percentage points of the 12 percentage point gap between GDP and its pre-crisis trend. Applying the same methodology to data from the UK, we find that GDP would be 8 percentage points higher absent the 2007-2008 financial shocks. For the euro area, we use a slightly modified approach and find that the financial crisis likely contributed to the persistent gap between GDP and its pre-crisis trend to a similar extent.

We do not yet know why recessions emanating from the financial sector have such persistent effects on economic activity. One possibility suggested by a number of recent studies is that tight credit conditions prevent firms from investing in research and development projects and stop new firms from emerging, which could permanently affect the economy’s productive capacity.

Avoiding the Next Financial Crisis

Our research points to a strikingly asymmetric relationship between financial market conditions and economic activity. An easing of financial market conditions has only a small effect on economic activity. By contrast, a sudden tightening of financial market conditions causes significant and highly persistent losses to the economy’s productive capacity.

As outlined by former Governor of the Federal Reserve System Jeremy Stein, the existence of such asymmetry supports the view that central banks should incorporate financial stability considerations directly into their monetary policy framework.

Central banks may want to loosen monetary policy when facing a shortfall in their inflation or unemployment rate targets. But when risk premiums are already low, further accommodation likely increases financial market vulnerability. This, in turn, raises the risk of a costly adverse financial shock and, hence, larger shortfalls from the central bank’s policy targets in the future.